Download this article as a PDF that you can print and share with your local officials, and head to the end to see 5 things you can do right now.

When Shawn Wathen decided to see how much his county was spending on purchases from Amazon, he wasn’t sure what he would find.

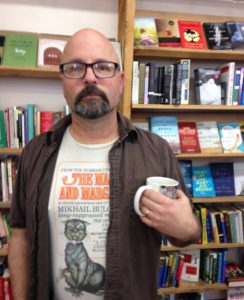

Wathen co-owns an independent bookstore, Chapter One, in Hamilton, Mont., a 4,500-person town nestled in the Bitterroot Mountains an hour south of Missoula. Wathen has seen a lot of stores come and go from downtown Hamilton in recent years, but Chapter One has kept on, along with the local newspaper and the office supply store, the toy store and the drug store, that are the bookstore’s neighbors on the same block of Main Street.

Amazon doesn’t have a physical presence near the town — no warehouse for storing goods and packing boxes, no sortation center or delivery station or one of its new brick-and-mortar bookstores — or, in fact, anywhere in Montana, but Wathen’s been increasingly impacted by its growth in recent years. After reading the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s recent report on the company, and talking about it with the Hamilton Downtown Association, Wathen started wondering if his local officials were buying from Amazon for any county purchases. He got in touch with the Ravalli County treasurer to find out.

After some back-and-forth with the county, and teaming up with another business to pay the $120 records fee, Wathen got back a report. Between reams of paper and ink cartridges, a handful of books and miscellaneous items like picture frames, Ravalli County had spent $15,500 purchasing goods from Amazon in 2016. Residents in the county have worked to stop chain retail proliferation for years, including successful campaigns to block two separate Walmart developments, but meanwhile, Amazon had snuck in under their noses.

It felt “a little bit like betrayal,” says Wathen. Wathen’s been at Chapter One for 21 years, starting out as an employee and later buying the business. He and his co-owner work at the store full-time; they pay property taxes, serve on local associations, host author readings, and organize book clubs and literature seminars. Chapter One is a small business, but in 2016, the bookstore gave $8,000 in discounts and direct donations to organizations in the county, including three school districts.

Ravalli County’s spending with Amazon isn’t an outlier. In February, U.S. Communities, a purchasing cooperative that negotiates office and school supply contracts for more than 90,000 public agencies across the country, announced that it had awarded Amazon Business a multiyear contract for 10 different product categories, including office supplies, classroom and art supplies, musical instruments, audio visual and electronics, and scientific equipment and lab supplies. In coming months, the public agencies that are members of U.S. Communities will be deciding whether or not to sign onto the contract. These agencies include everyone from major city governments like Boston and Minneapolis, to school districts, townships, libraries, fire departments, and sewer districts. In its Request for Proposals, U.S. Communities estimated the overall value of the contract to be $500 million per year.

While U.S. Communities described the contract as “competitively solicited, evaluated, and awarded,” independent business owners quickly disagreed. “The way the U.S. Communities bid was written proves yet again how the system continues to be rigged against open and fair competition,” the National Office Products Alliance, the trade association for independent office supply dealers, described in a statement. “In order to bid on the U.S. Communities contract, a bidder had to bid on all nine categories,” which included not just office supplies, but also grocery, clothing, animal supplies, and more. “These requirements made it impossible for anyone other than Amazon to bid on this contract.”

As public officials are increasingly turning to Amazon for their buying needs, citizens need to be concerned. For starters, there’s evidence that when public officials buy from Amazon, whether through piece-meal purchases or through a formal contract, they overpay. In the case of Ravalli County, when local business owners saw the report of the county’s spending with Amazon, they also saw that their businesses could have offered the county lower prices. Take copy paper. While the county was spending $12 per ream on paper from Amazon, it was available at the local office supply business, the Paper Clip, for $8.50.

This overpaying is a widespread trend, says Rick Marlette, whose company, OP Software, monitors office supply prices. “I guarantee anyone consistently buying office supplies from Amazon will be overpaying,” Marlette wrote in an email. In the case of the U.S. Communities agreement, Marlette points to a number of problems in the contract, including that “prices shall remain firm” for the five-year term. There’s a history of public agencies getting ripped off by these deals: When Office Depot held the U.S. Communities contract for office supplies, it came under investigation by attorneys general in Florida, Texas, California, and a number of other states for misleading government customers into paying higher prices than outlined in the contract. Office Depot ultimately refunded cities and states for overcharges that ran into the millions of dollars.

On top of these direct costs, Amazon also costs cities and towns in other ways. Amazon has no presence in most of the places where it does business, and its growing market share is causing widespread retail vacancy, and along with it, declining property taxes, which are the leading source of revenue for state and local governments. The Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s recent report on the company found that by the end of 2015, Amazon had caused more than 135 million square feet of retail space to become empty nationwide, and research from the firm Civic Economics has estimated that land use changes triggered by Amazon led to a loss of $528 million in property tax revenue in 2015. Amazon’s increasing dominance is also impacting communities in less quantifiable, but equally critical ways, from a decline in the vitality of city streets to weaker social bonds.

Meanwhile, as spending shifts to Amazon, it also stops getting recirculated through the local economy. When people and institutions spend their money with locally owned firms, those firms not only keep a larger share of their payroll and profits locally, but also in turn rely on and generate local supply chains, creating an “economic multiplier” effect. Amazon’s payroll and revenues, in contrast, are concentrated at its headquarters in Seattle; it doesn’t have local rents or loan payments, and it also doesn’t need local accountants for its taxes or local agencies for its advertising campaigns. For most communities in the U.S., when money is spent at Amazon, that money just leaves.

Instead of sending taxpayer dollars out of the community, public officials can choose a different way. Cities and states have long recognized that their spending can be a powerful tool to advance other public priorities, and many have adopted policies that give a preference to businesses that meet certain characteristics, like local ownership. In cases where the goods or services aren’t large enough to go out for bid, such procurement policies can direct officials to simply check with locally owned businesses first; in cases where the goods or services do go out for bid, these policies can give the locally owned business a price preference, such as within 10 percent of other bids, in order to recognize the additional value that spending locally brings to the city or county.

Along with supporting and growing the local economy, these policies can actually benefit a city’s finances, even if it means spending a little more. Each additional dollar that circulates locally boots local economic activity, employment, and, ultimately, tax revenue. The way Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson has described it, local purchasing comes down to “self-help.”

The City of Phoenix offers one example of what this looks like in practice. For years, the city had a contract for its office supplies with Office Max Contract, a national company that has a presence in the state. In 2007, the research firm Civic Economics conducted an economic impact study comparing Office Max with a locally owned company, Wist Office Products. The study found that just 11.6 percent of the money that Phoenix spent with Office Max stayed in the local economy, but that if the city switched to Wist, given its local ownership and local supply chains, that figure would jump to 33.4 percent. In a one-year, $5 million contract, that meant the difference between $580,000 staying in the local economy with Office Max, and $1,670,000 with Wist. Eight years later, in May 2015, Wist finally won the city contract.

Warms my heart to see a @wistoffice delivery truck outside @CityofPhoenixAZ City Hall! Keep it local, folks! @LocalFirstAZ pic.twitter.com/1xD94H1Yym

— Kimber Lanning (@KimberLanning) March 21, 2017

Back in Ravalli County, last week, Wathen, along with the father-and-son team that owns the Paper Clip and the head of the Hamilton Downtown Association, met with the county commissioners. In a rural and politically conservative county, Wathen found that the commissioners were receptive to his economic points. As one of the commissioners explained it to the local newspaper, there hadn’t been a policy change encouraging county offices to buy online; it was more the slow, steady trickle of the absence of a policy, and county employees switching over to Amazon by default. “I think it was a shock” to them, Wathen says, “that there wasn’t a policy in place to ask around locally.”

By the end of the meeting, the commissioners asked the business owners to come in and talk with the department heads who oversee purchasing, and also agreed to look into a local purchasing preference. “To me, if it’s the same price or even close, it’s a no-brianer,” Commissioner Jeff Burrows told the Ravalli Republic. “We all understand the benefits of spending the county’s money locally.” Among the other perks of shopping locally, in this case, there’s even faster delivery than Amazon can offer: When the county orders office supplies, “I’ll walk the three blocks to bring it here,” the owner of the Paper Clip told the commissioners.

Even if the county does decide to shift its spending, it doesn’t buy a lot of books, and the immediate dollar impact on Wathen’s business may be slight. But the new mindset that such a shift would signal would be significant. “I think what can’t be ignored is the impact of saying, ‘We value you and we’re going to put that where we live,’” Wathen says. “It’s a mental shift that you can’t discount the impact of.”

What you can do:

- Check to see if your local government agencies are part of U.S. Communities at this link: <http://www1.uscommunities.org/about-us/registered-agencies.aspx>. If they are, contact your local officials and urge them not to sign onto the contract with Amazon Business, but instead to reinvest taxpayer dollars in the local economy.

- Reach out to reporters at your local newspaper with a tip to look into local government spending with Amazon, and to do a story on how local public agencies are interacting with the company.

- Get in touch with your local officials — for instance, your school board member, city council member, county commissioner, and state representative and senator — and ask how much your school district, city, county, or state spends with Amazon. Encourage them to adopt a local purchasing policy.

- Read and share resources about the value of local procurement policies, such as our article, “Procurement Can Be a Powerful Tool for Local Economies, but Takes More Than a Policy Change to Work,” and our resource page, “Local Purchasing Preferences,” with the text of other communities’ policies.

- Use our data! It’s helpful to have facts and figures on hand when starting these conversations. For numbers about the economic returns of spending locally, see our “Key Studies” page. For numbers about Amazon’s impact on local economies, download our report on the company, “Amazon’s Stranglehold,” and flip to p. 7 and p. 53. As Shawn Wathen told us, when he met with his county commissioners, “The economic data that ILSR provided made for a stronger argument. Without that, a lot of it would be anecdotal.”

Download this article as a PDF that you can print and share with your local officials.