Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

San Francisco has one-third as many chain stores as the national average. That’s thanks in large part to a city ordinance that restricts “formula” businesses. Enacted in 2004, and expanded in 2006 and 2014 (with input from ILSR), the policy permits formula businesses to locate in the city’s neighborhood business districts only if they pass a special review. The policy works to promote commercial diversity, and along the way, it’s also given citizens more of a role in shaping their neighborhood,Our guest, AnMarie Rodgers, has played a key role in implementing the policy. She is the Senior Policy Advisor for the City of San Francisco’s Planning Department. As she explains in this episode, the staff members of the city’s planning department were not enthusiastic about the ordinance when it first passed, but as they’ve implemented it and studied its results, they’ve become believers in its value.

In this episode of the Building Local Power podcast, ILSR Co-director Stacy Mitchell and ILSR researcher Olivia LaVecchia talk with Rodgers about the history of the policy and how well it works, and what advice she has for other cities who want to do it too.

The trio delve deep into what qualifies as a chain store under the formula business restriction policy. It includes two of these criteria: signage, merchandise, logo, and architectural similarities and having eleven total locations. They also discuss how this neighborhood-by-neighborhood approach allows citizens to determine their own future and prioritize equity and affordability.

“Part of doing business in San Francisco is that a chain store needs to prove it’s a good fit for the neighborhood and they cannot take that for granted anymore,” says AnMarie Rodgers, Senior Policy Adviser for the City of San Francisco.

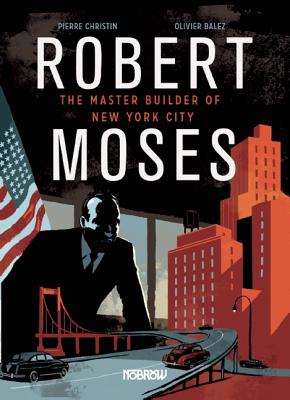

ILSR Rule Archive: Formula Business Restriction – San Francisco, CA — This post from ILSR’s rules archive sets out the formula business restriction policy and details how the policy benefits the local neighborhood economy. How San Francisco is Dealing With Chains — This post from ILSR’s Stacy Mitchell tells the story of the formula business restriction policy in San Francisco and the history about how it came about, building equitable and local economies. Formula Business Restrictions — An overview of this type of policy, include examples of other cities, besides San Francisco, that have adopted it. Report: Monopoly Power and the Decline of Small Business — This report from ILSR’s Stacy Mitchell details how the United States is much less a nation of entrepreneurs than it was a generation ago. This report suggests that the decline of small businesses is owed, at least in part, to anticompetitive behavior by large, dominant corporations. What Neighborhood Retail Gets Right – Episode 27 of the Building Local Power Podcast — This podcast between ILSR’s Stacy Mitchell and Washington D.C.-based founder of several Ace Hardware stores detail the power of neighborhood retail and the ways her stores are faring in the age of big-box retail and Amazon. Our guest, AnMarie Rodgers, gave a great recommendation for the long history and the dialog between urbanist Jane Jacobs and New York City developer Robert Moses, epitomized by the book, Robert Moses: The Master Builder of New York City. It’s this last policy, San Francisco’s formula business policy, that we’re going to spend much of our time talking about today. This local planning law prohibits chains from locating in some zones within the city and requires them to obtain a special permit to open in other zones. The result is that while many other cities are covered in Starbucks outlets and chain drug stores, and national bank branches, and the like, San Francisco’s neighborhood business districts remain largely comprised of independent businesses. AnMarie welcome to the show. I could only do that for about six months and then I took a job actually doing habitat restoration for a non profit, but then I was not able to afford living in San Francisco because it is expensive there and non profits don’t pay very well. I looked back for city employment. There were no jobs at that time for landscape architects, but there was this weird city planning gig, and you could get that job if you had a graduate degree in a design related field like I did. I knew a friend who actually studied urban planning with me at the University of Michigan. I took her out for drinks and I said tell me everything that you know about urban planning and if I get the job I’ll buy you a bicycle. So we sat down for an hour and she said all that you need to know is about Jane Jacobs. Talk about Jane Jacobs and eyes on the streets. I did that in my interview. I got the job in 99 and I could not be happier. I’m committed to public service and I feel like being part of the guiding vision of the city that I live in is really important. Prohibiting the externalities related to the car was a early focus. Then we went through looking at a similar problem where we had an explosion of pharmacies in the early 2000’s and chain coffee stores that were all just kind of co locating next to each other in a density that was, you couldn’t imagine. It ended up being a Walgreen’s on one corner and directly across the streets would be another pharmacy, a Rite Aid. It seemed like there was no end to the expansion in their efforts to get both a dominance over the commerce, but also to get a real estate foothold in the city. Then we started looking at those uses, and the planners hadn’t really found the right mix. In 2004 a progressive politician named Matt Gonzalez actually started the first law and it was the basis of the law we still have today. The definition that he used had been similarly developed in another California city and it focused on looking at the identifying standard features. If a business had standardized signage, standard merchandise, a logo, the architecture, if they had at least two of these standard features then they became formula retail if there were more than 11 of them. With that in place, we for the first time had a definition of what a chain store might be. It was then regulated depending on where we located. Like I said before, in some of the downtown districts, the office districts, or our regional shopping districts, there was no regulation of it. They could just be permitted as a normal business, but in our neighborhood shopping streets he required neighbor notification and also there was a couple of neighborhoods where it was actually prohibited. We did the neighbor notification with the earlier version of the pharmacies and the chain stores. Matt Gonzalez actually instituted the conditional use. Earlier, when we were grappling with pharmacies and drug stores, the burden was on the neighbors. When Matt Gonzalez came with his new law, he flipped it so now the businesses, the burden was on them and they needed to prove that they were either necessary or desirable to locate in a community. That it would help with the turnover by pricing out low income people from neighborhoods. There was a lot of dialog when it was first put into place about whether it was the appropriate for San Francisco, and Matt Gonzalez and some of the other elected officials in his party decided that it was really important. By putting it in place by a voter’s initiative, the law is much stronger. It can only be weakened or overturned by another vote of the people. It’s a pretty high threshold to educate people and to get them to vote on a referendum, and they did that. It passed by 56% when it was on the ballot in 2006. Then it was solidly part of the law. People understood it was not going to be going anywhere. I think after that referendum, planners came to grips with it, the business community came to grips with it. Everyone seemed to understand that this was a part of doing business in San Francisco is that a business that was a chain store needed to prove that they were a good fit for the neighborhood and they couldn’t just take it for granted that they could be located. After 2014, and after we did our study, we really understood a lot more about how the law was functioning both for businesses and for our neighborhoods. That’s when we started to embrace it too. I think that the tide just turned over the course of that 10 year period from when it started in 2004 to 2014. The majority of applications for formula retail in places where it was regulated ended up being approved. Despite the business community saying that this is a unnecessary obstacle to commerce, 75% of the applications were in fact approved. I think that community certainly understood what a useful tool it was for them to keep businesses out that were not compatible. It was really only when the community fully organized and came to the commission hearing to make their arguments that applications were disapproved. When we have an application before the planning commission, they are looking at the existing concentrations of formula retail that already exist in that neighborhood where the proposal is. They’re also trying to see if there’s availability of other similar retail uses within the district. If we have a Subway sandwich shop moving into the district, is there already a deli or two that’s meeting that same need. We also look at the price ranges too, because we know that equity is important to our commission. So then we do a compatibility check of the proposed formula retail architecture with the neighborhood commercial district character. That’s really not quantitative, that’s really a qualitative review. Then we also, as far as quantitative reviews look at the vacancy rates. Sometimes where we have formula retail controls there have been higher vacancies, but it varies more by neighborhood and by certain characteristics within the neighborhood than it seems to do by the concentration of formula retail or independent businesses. If we have a neighborhood that’s struggling with high vacancies, the community might be more open to a formula retail at that point instead of a vacant store front. Lastly, we look at the mix of neighborhood serving uses compared to city wide or retail serving uses. In San Francisco because we are a transit oriented city, we want to make sure that everybody can meet their daily needs within an easy walk. Within a quarter mile of your house you should be able to buy everything that you need from groceries, to toiletries, to simple services. If a neighborhood is low on neighbor serving uses and a chain store is meeting those, we might look more favorably upon the chain store, but if it’s already low on neighbor serving uses and it’s a high end retail store that’s not helping people do their daily shopping, then that would be a factor not in favor of that particular chain store. If you’re a regular listener to this podcast, you know that we don’t have any corporate sponsors who pay to put ads on the show. The reason is pretty simple. Our mission at ILSR is to reinvigorate democracy in local communities and to decentralize economic powers. We’re big believers in local businesses and community banks, and family farms. For those local businesses it doesn’t make a lot of sense to advertise on a national podcast, and so we rely instead on you, our listeners. Your donations not only underwrite this podcast, but also help us produce all of the research and resources that we make available on our website, and all of the technical assistance we provide to grass roots groups. Every years ILSR staff helps hundreds of communities challenge monopoly power directly and rebuild their local economies. So please take a minute and go to ILSR.org and click on the donate button. That’s ILSR.org and if making a donation isn’t something that you can do right now, please consider helping us in other ways. One of the best things you can do is to rate and review this podcast on iTunes, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts. Ratings help us reach a wider audience. They push us up in the search results, so it’s usually helpful when you do that. So today we’re talking with AnMarie Rodgers, senior policy advisor for the city of San Francisco’s planning department, and we’ve been talking about San Francisco’s formula business policy. This is a policy that there are quite a number of smaller communities around the country that have a policy similar to this, but San Francisco is the only large city that has such a policy and they’ve had it in place now for about 13 years. Since we’re talking a little bit about how it’s working and how well and how support for it really has been growing. AnMarie I want to pick up on something that you said before the break. I really want to underscore what I think is so great about this policy in terms of how its been implemented, which is that it’s neighborhood by neighborhood. As a conditional use permit and so there’s a process by which the city and the neighbors actually review the particular proposal in light of that business district. If it’s a formula business that’s going to add something that the neighborhood needs, then it’s going to get the green light where if it’s going to take it in the direction that isn’t the right mix. It’s going to be something that maybe gets turned down. I love that there’s that flexibility and that the city’s policy really recognizes that different neighborhoods are in different places and what works somewhere may not work somewhere else. Can you talk a little bit about how this policy intersects with issues of equity and neighborhood serving uses. When we think about what’s important in terms of retail affordability, being able to serve neighborhood needs are really important factors. I know some people think chains are always lower priced. How does that issue play out in terms of how this ordinance works. We could see that formula retailers tended to employ more people in total, but we also had a sense that there were a good mix of part time folks, and what was the exact mix between part time and full time. We didn’t know that. Colloquially, we heard that there were more full time employees in the independent businesses, but that again was not verified. Also, San Francisco is pretty lucky in that we have a lot of baseline laws that established a floor to protect the lowest income workers for things such as healthcare. We have a higher minimum wage allowance, and all kinds of worker rights bills that apply to any business of a certain size. The differences between the two independent and formula retailers might not be as broad in San Francisco. What became more important and where the difference is would be the affordability of goods, and that’s why I think to which you mentioned earlier the case by case review is really helpful because it allows neighbors to say if this is something that helps them to be able to succeed and thrive in San Francisco. If it helps them get affordable groceries or affordable medicines, that would be an important consideration for the commission. One of the other things that we sometimes hear on the pushback side is this idea that the market will determine where businesses open, close, what businesses open, close. How do you speak to that, the role of policy in addressing that here? We recognize that there are these larger values and impacts that what one person does has all these effects on the surrounding neighbors, and on the community, and that in fact the value, I mean the reason that San Francisco real estate is so expensive in part is because of all the contributions of its residents to making it such a great city. All of the local businesses there, so a value is created by the community, it seems only right that the community then structure how the city grows and develops because it’s all interconnected right? I want to turn now to other cities, other communities, that might be thinking about doing something similar to what San Francisco has done in terms of regulating formula businesses. What do you think that cities should think about? Are there things that you wish you had known back when San Francisco started down this path? Are there things that would’ve been helpful and just what would be your advice in general to a community that comes to you and says we’re seeing more and more chains come in. We’re not sure that the mix that we’re getting is really right for the community. How should we go about this whole process of looking at this approach? That is not going to happen. It’s widely established that there is a city interest in securing the general welfare. Zoning can be used to help protect the general welfare and secure a diverse commercial district for a variety of services. Also, to guide a steady considerations. Those are all within the police powers of the city, and those are a proper use of the zoning tool for your future, but zoning cannot be used to reduce competition or to lower commercial rents. Regulating commerce is not a function of local government instead in the US that’s a function of our state and federal governments. That’s one principle, is to look at what are the real powers that municipalities have and how they can write these laws. Secondly it’s an idea about regulating the use instead of the user. The land use type and planner speak is something like a retail use, an industrial use, a residential use, then you can break those down into further categories like for retail you also have a restaurant use, a grocery store, and that’s where the formula retail is a subset of the retail use so it’s important when you’re trying to define what is a formula retail use that you have a solid objective definition of what a formula retailer may be. Formula retail use definitions often talk about the homogenizing factors of formula retail. The standardized goods, designs and aesthetic that I described earlier. To be legally defensible, formula retail laws cannot look at who the owner may be or where the owner lives. If a store meets these objective criteria, then the law applies even if it’s a home grown business. I think that’s more complicated than the average planning department wants to get with their ordinance, so it might be easier to start with just looking at the United States and where you might see homogenizing uses. I think the idea of including international chains is more important in a city like San Francisco because when you have a large international store, they often want to set up a flagship store in San Francisco or a similar city as their foothold into the US. That’s why we consider international businesses. Our own economists recognize the economic value of the uniqueness of San Francisco as something that matters both for employers and for residents. From his perspective, employers can pay residents less because it was so pretty. That’s one reason why having good aesthetics was helpful for employers. Obviously from just a satisfaction point of view, it’s really nice to have your city be unique and have its own character. For your neighborhood too. His review concluded that only the commission and the neighbors together can decide whether a business is appropriate or not for that neighborhood. I think in all planning issues, it’s also important to consider not only the democratic process that happens at the commission, but also the democratic process that can sometimes be lost through a public process when disempowered groups are not able to be there and represent themselves as fully. At one point during all these proposals and talks about changing the law, somebody wanted to delegate the decision to a neighborhood group. First of all, that’s not defensible legally, but it was also disconcerting in that it would really focus on the people who had the luxury of time to engage with this neighborhood group. We would see business proposals that fit their needs as opposed to thinking about everybody who lives in the community, which is the benefit of government. They’re appointed to look at the broader interests and not just the micro interests. While you’re there you can sign up for one of our newsletters and connect with us on Facebook and Twitter. Once again, please help us out by rating this podcast and sharing it with your friend. This show is produced by Lisa Gonzalez and Nick Stumo-Langer. Our theme music is Funk Interlude by Dysfunction Al. For the Institute for Local Self Reliance, I’m Stacy Mitchell. I hope you’ll join us again in two weeks for another episode of Building Local Power. If you have show ideas or comments, please email us at info@ilsr.org. Also, join the conversation by talking about #BuildingLocalPower on Twitter and Facebook! Audio Credit: Funk Interlude by Dysfunction_AL Ft: Fourstones – Scomber (Bonus Track). Copyright 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license. Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and, for monthly updates on our work, sign-up for our ILSR general newsletter.

Stacy Mitchell:

Hey AnMarie, I heard you had a stat to start us off today.

AnMarie Rodgers:

Yeah. I do. I was thinking about 12%.

Stacy Mitchell:

What is 12%?

AnMarie Rodgers:

12% represents the number as a percentage of formula retail that we have in San Francisco as a percentage of all retailers. So only 12% are formula retail.

Stacy Mitchell:

How does that compare to the national average?

AnMarie Rodgers:

That is significantly lower than the national average. The national average is about 32% of retailers across the country are formula retails.

Stacy Mitchell:

Wow. So San Francisco has about 1/3 as many chain stores as the national average.

AnMarie Rodgers:

That’s right. That’s a city wide average. You got to keep in mind that we don’t regulate formula retail across the entire city. Some of our downtown core areas or the tourist district around fisherman’s wharf, formula retails is permitted as a right. We have higher levels of formula retail in those areas, and in our neighbor chopping streets, which is where most people live and kind of get their community identify it’s even lower. It’s around 10%.

Stacy Mitchell:

Hello and welcome to Building Local Power. I’m Stacy Mitchell of the Institute for Local Self Reliance. On today’s show I’m joined by my colleague, Olivia LaVecchia. Hello Olivia.

Olivia LaVecchia:

Hi, Stacy.

Stacy Mitchell:

And by our guest, AnMarie Rodgers, whose voice you just heard. AnMarie is the senior policy advisor for the San Francisco planning department, where she’s worked since 1999 and where her achievements in community planning have been recognized with the US Congressional Commendation. AnMarie’s work has been pivotal to making San Francisco’s housing policy more just and expansive, and she has also shepherded new city laws for green landscaping, urban agriculture, and formula retail businesses.

AnMarie Rodgers:

Thank you very much. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Stacy Mitchell:

I’m so glad you could make it. I read that you grew up on a pig farm in Iowa, and I’m really curious how it is that you ended up being an urban planner in a big city like San Francisco.

AnMarie Rodgers:

You know, it surprised me too to end up as a city planner. It was unexpected. I moved to San Francisco in 1991 to work for the public health department. After a little bit working in that field I wanted to get a little bit more intellectually challenged, so I went back to graduate school and studied landscape architecture with an emphasis on natural resources. I thought I was going to be designing wetlands, and native habitats, but I did want to come back to San Francisco, and when I got back to San Francisco those jobs were occupied more by scientists than by designers so I took a job developing sub divisions and golf courses in the easy bay. I was killing my soul.

Olivia LaVecchia:

It’s great to hear more about how you’re coming to this and I’m excited to talk with you about San Francisco’s formula business ordinance and how it’s part of creating that city too. I know that the policy was enacted kind of in an early version in 2004. Then there was a ballot initiative in 2006 and it was strengthened in 2014 with some other tweaks along the way. I’m wondering if you can start by just speaking to some of that context. What was happening in 2004 that the city decided to move forward with this? What were some of the issues you were looking to address?

AnMarie Rodgers:

The city has struggled with formula retail related businesses without calling it that since at least the early 80’s with the beginning of the fast food chains in the city. The drive up windows, the vehicular oriented architecture, it didn’t sync with the city, and residents often felt that the litter and trash associated with those uses were changing their neighborhoods for the worst. We started off looking only at fast food retailers and how we might regulate those.

Stacy Mitchell:

So it was in 2004 that Matt Gonzalez instituted this conditional use permit, and then there were a few neighborhoods where formula businesses were just banned outright. Am I correct in remembering that there was referendum on the policy? Was that because people didn’t like it and wanted to overturn it or people liked it and wanted to make it stronger? What happened because that was a couple years maybe after it initially passed?

AnMarie Rodgers:

I think it’s fair to say that when the law first went into place there was skepticism from several quarters. Planners were certainly one of them. We were not sure that there was really a land use issue. This idea of chain stores, there were some from the business community that were arguing that it was discriminatory against successful businesses, and there were also legitimate concerns from low income people that chain stores may be providing critical goods and services in the only manner that they can afford them. So some saw that as a tool of gentrification.

Olivia LaVecchia:

That’s not a slim margin that it passed by. You know either leading up to the ballot initiative or just working on this policy in general, are there things that the city has done to build support for it or to build understanding for what it is and how it works?

AnMarie Rodgers:

That is a good question. In 2014, we had a number of elected officials that were trying to change the law and adapt it. That was really the first time the planning department did a study and really tried to understand is this working, is this helpful for us. Before then, our positions about the formula retail law had been critical or certainly questioning about the public good.

Stacy Mitchell:

That’s really interesting to hear that history because I wasn’t aware having followed this, I mean it’s interesting to hear you say that the planning department and the city itself wasn’t really maybe fully on board with this approach. That it had in a way come maybe a little bit more from the margins as an idea, was implemented, was approved by voters, but maybe the city was a little uncertain about it, but as time went on and as you studied it and as you looked at it, it’s now become something that the city has really embraced. That’s really interesting to hear.

AnMarie Rodgers:

That is the case for if you consider the city the bureaucracy and the department in the regulatory function that we serve in that aspect. If you consider the city, as I’m sure our elected officials do, to be the policy makers led by the politicians, then they were on record in 2004 saying that this was an important thing to do for San Francisco. The voters were on record shortly thereafter saying the majority of the voters felt it was appropriate. It took some time for the bureaucracy to catch up and embrace the thinking as well, but we did.

Stacy Mitchell:

Break this down in terms of what this actually means. My understanding is that the ordinance covers about half of the commercial space in the city so it covers all of the neighborhood business districts, but it doesn’t cover the downtown. It doesn’t cover sort of the tourist zone. Those places are open to formula businesses more or less, but it’s the neighborhood business districts that are covered by this ordinance. Break down how those districts are now different from other parts of the city as a result.

AnMarie Rodgers:

In the neighborhood shopping streets where we have been regulating formula retail since 2004, only about 10% of the businesses are formula retail. As I mentioned at the start of the show, about 12% across the city are formula retail, but if you look at the space occupied it becomes even more kind of a dramatic comparison because formula retailers are generally larger businesses. They’re usually, in San Francisco, more than 85% of them are in stores that are 3,000 square feet or larger. At the square footage level, instead of being 12% of retailers city wide, they’re 31% of all the retail space city wide.

Stacy Mitchell:

You mentioned that three quarters of all the applications for formula retail businesses get approved, there’s a bit of a deterrence effect which I think is really interesting that in affect businesses that want to locate, they only apply if they really feel like they have a good case to make for getting into that neighborhood. Chains don’t even apply to come in unless they think they can really make that case that they’re going to be great for the neighborhood. Is that right?

AnMarie Rodgers:

That’s right. That’s something that we talk about and we understand, but it’s really hard to support with statistics. You have no idea where, unless you’re a real estate agent, where businesses are thinking about locating, but we do know that we get applications that are initially submitted and after talking to planner staff and the neighbors, they withdraw their applications. So we have stats on the withdrawals, but we don’t know how many never even consider locating in these areas because of the controls.

Olivia LaVecchia:

I think it’s really interesting too, what you said earlier about the burden of proof. So you know maybe before, if a national chain wanted to move into a neighborhood, it would be up to the neighbors to find out that that’s happening, and then if they don’t think it’s a good fit to have to organize around that, whereas now there’s notification. There’s a hearing and it’s really more on the national chain to make its case that it has something to add to the neighborhood. Can you speak to some of the criteria that are part of the permit and what the chain has to do to make that case?

AnMarie Rodgers:

So in San Francisco we call that discretionary permit review, a conditional use authorization that’s pretty widely used as a zoning tool across the country. Sometimes they call it a special use permit. The criteria of the planning commission looks at in San Francisco have to do with both locational criteria as well as aesthetic considerations.

Stacy Mitchell:

You’re listening to AnMarie Rogers, senior policy advisor for the San Francisco planning department. I’m Stacy Mitchell with the institute for local self reliance. We’ll be right back after a short break.

AnMarie Rodgers:

When you’re talking about equity in formula retail I think there’s a couple of different ways to look at it. You can look at it from the consumer perspective and are the goods and services affordable to people that live in the neighborhood. You can also look at it from the employment perspective. What sort of benefits are being provided to the workers there? Are they full time or part time? Unfortunately, this area of employment and pay was an area that we were not able to get that much data about San Francisco because of the confidentiality related to people’s salaries.

Olivia LaVecchia:

That’s such an important point that it is case by case and that the neighbors get to assess as things come up instead of kind of having a blanket understanding of how a store might operate. It is, I think important to draw the nuance there because it’s one of the things we sometimes hear when we’re talking about equity and independent businesses. Concerns about expense and exclusivity and right, it’s in fact a lot more married and there are the employment considerations as well as the consumer considerations.

AnMarie Rodgers:

In San Francisco we’re not shy about the fact that we feel government has a role to play and helping citizens realize the future that they want. The idea that the market is going to necessarily serve low income people, I don’t think that’s a main stream idea in San Francisco at least.

Stacy Mitchell:

The question I think Olivia asked really goes straight to the nature of why we have city planning policies in the first place, right? If we all thought we should leave everything to the market, then my neighbor could bulldoze his house and build an incinerator piping out all kinds of nasty gases next door to me.

AnMarie Rodgers:

Well I’d recommend that you look at a couple of basic legal principles as the foundation for how to develop a formula retail law for your own community. If you do believe that there is a use to zoning, if you really think about it, I’m pretty sure everyone does believe that. Even in Houston, where there’s allegedly no zoning, there are in fact a review process that helps guide development. Nobody wants to see a hog refinery, or a slaughter house right next door to residential use.

Stacy Mitchell:

That’s great to clarify. The legal issues, that it’s really, essentially that if Starbucks wants to open a unique coffee store that you wouldn’t recognize as a Starbucks, then they wouldn’t count as a formula business. Is that right?

AnMarie Rodgers:

Yes. In San Francisco they wouldn’t count as a formula retail until there were 11 of those new Starbucks iterations. Some cities have lower thresholds. So the numerical threshold concern as low as three or four. Also, interestingly, in San Francisco, we now look at how many locations there are across the entire world. When we get an application with a foreign business, we actually have to try to Google search and understand how many of those businesses might be in Thailand, to see if they would qualify as a formula retail in San Francisco.

Olivia LaVecchia:

Also, thinking about advice to other cities. I’m curious, you know, as the law has been in place over these 13 years now, in some version, just what you’ve learned about how it works. Is there anything you wish you had known at the start of this process that would be useful for other places?

AnMarie Rodgers:

I think probably the most shocking thing for me was when our cities economist reviewed the law. Because if anyone is familiar with an economist, they are looking purely at a fiscal basis. When people think about their communities and when planners evaluate proposals, we’re thinking about many more factors than just the economic review. However, our own chief economist, when he reviewed the law in San Francisco, he thought about many different factors and talked about all these different economic impacts, but where he landed was that it is really important to consider from an economic perspective, how unique your neighborhood is and how a new business fits in with the neighborhood aesthetic.

Stacy Mitchell:

This has been so great. I’ve just, it’s been terrific to hear more about how this ordinance has worked and also about how the city of San Francisco thinks about these issues and how they play out. I want to just close out the show the way we often do, which is asking if you have a reading recommendation.

AnMarie Rodgers:

Well I mentioned earlier that Jane Jacobs was seminal to me entrée and to city planning, so I think part of the point counterpoint is the dialog between her and Robert Moses. Which there’s an incredibly large book about Robert Moses. If that’s a little bit too intimidating, I would really encourage people to check out the graphic novel titled “Robert Moses, The Master Builder of New York City” because that really crystallizes so much of this dialog.

Stacy Mitchell:

AnMarie thank you so much for being on the show today.

AnMarie Rodgers:

Thank you. It was my pleasure.

Stacy Mitchell:

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Building Local Power. You can find links to what we discussed today by going to our website ILSR.org and clicking on the show page for this episode. We’ll put up copies of some of the studies that AnMArie talked about. Links to the ordinance. All sorts of information if you want to know more. That’s ILSR.org and just click on the show page for this episode.

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage. Subscribe: iTunes | Android | RSS

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()