Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Since the 1980s our guests Dan Knapp and Mary Lou Van Deventer have cared about salvaging valuable materials from the waste stream and bolstering their local Berkeley, California community. That’s why they established Urban Ore and have been fighting for local reuse policies and against distant, dirty incinerators.

In this conversation for our Building Local Power podcast, the pair join ILSR co-founder Neil Seldman and Communications Manager Nick Stumo-Langer in discussing the history of Urban Ore and their activism in the Berkeley community.

“One of the secondary economic impacts of our enterprise, we salvage at the dump, so everything that we take off the transfer station floor doesn’t become landfill. So that’s pollution prevention right there. We prevent pollution, and then the stuff we’ve rescued we distribute through retail sales,” says Mary Lou Van Deventer of the impact Urban Ore has on the Berkeley, California community.

“So we provide low-cost goods to the community that will raise the standard of living for people”

Our guests, Dan Knapp and Mary Lou Van Deventer, provided a number of recommendations for our listeners to learn more about their perspective in running Urban Ore in Berkeley, Calif.:

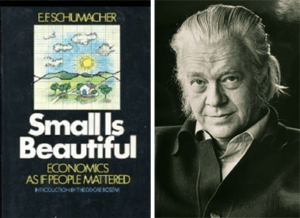

- “Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered,” by E.F. Schumacher

- “Buddhist Economics: An Enlightened Approach to the Dismal Science,” by Clair Brown, Ph.D.

- “The Zero Waste Solution: Untrashing the Planet One Community at a Time,” by Paul Connett (guest of Building Local Power episode 35)

- “Podcast: January 26, 2018, Dan Knapp Co-Founder of Urban Ore,” published on In Deep Radio

- “Life and Fate,” by Vasily Grossman

- “Politics and the English Language,” a short essay by George Orwell

- “Animal Farm,” by George Orwell

- “Homage to Catalonia,” by George Orwell

- Building a Zero Waste World, One Community at a Time (Episode 35) — Zero waste activist Paul Connett joins ILSR’s Neil Seldman and Nick Stumo-Langer to detail how to move communities across the world to a zero waste reality as well as how this activism fits within the grassroots landscape.

- Zero Waste: A History & Primer — If you haven’t noticed, the U.S. recycling movement has become a Zero Waste movement, and the Zero Waste movement is spreading rapidly worldwide.

- Municipal Waste and the Benefits of Re-Use — When it comes to municipal solid waste, it wasn’t that long ago that cities focused almost entirely on disposal. Only in the last 25 years or so have they begun to embrace recycling and materials recovery. The new strategy was spawned largely because of environmental concerns, but cities quickly learned that, once separated from the waste stream, used products and materials can form the basis for significant economic efforts — efforts that benefit some of their most disadvantaged residents.

- The True Value of Recycling and the Waste Stream (Episode 2) — In this episode, Seldman discusses the benefits of ILSR’s recycling work and responds to comments critical of the economic benefits driven by recycling.

| Neil Seldman: | It’s a pleasure to have Dan Knapp and Mary Lou Van Deventer, principals of Urban Ore, one of the pioneering recycling and reuse companies in the United States, and two pioneers of both the recycling and zero waste movement. They have contributed ideas, actions, and very innovative strategies that have propelled the US recycling and zero waste movement. Among the ideas they introduced were the twelve category market sorting system for dealing with true source separation has now become the basis for zero waste planning.

Dan came back from Australia in the early to mid 90’s, and brought with him the concept of zero waste that has been growing leaps and bounds. Both Dan and Mary Lou have described what’s going on in Berkeley, which has about an 80% recycling rate as the recycling ecology of commerce. A group of six different groups, companies, nonprofits, and government agencies that are pooling together to make Berkeley one of the best recycling cities in the world. And they’re also very deeply involved in many national and international issues concerning incineration and zero waste around the globe. During the interview, I’m going to ask them about how they got started in the anti-incineration efforts. But now before we start our interview, I just wanted to tell one of my favorite stories, and I have to emphasize one, because I have many. That is when Dan drove east through the night to come to a very special meeting in 1980. Actually, it was January 1981, of about 120 recyclers and environmental engineers to talk about recycling, this was in the middle of the heyday of planning and building incinerators. Dan walked to the head of the room, and he plunked down a big canvas bag with a big clunk, and he introduced himself saying, “I’m Dan Knapp, and I salvage landfills, and here’s my working capital. I recovered all these tools from the landfill.” And, of course, he gave a tour de force on recycling and reuse, both environmentally and economically. And there upon the waste engineers in the room revolted. And we had a wonderful discussion between the old paradigm dime and the new paradigm. So that was one of the many great memories I have of Dan. And I have equal great memories of Mary Lou, who is just the most wonderful environmental writer you can imagine. And both of them have really been intellectual stalwarts of the recycling and zero waste movement. So with that introduction, I’m going to turn it over to Nick to ask the first round of questions. |

| Nick Stumo-Langer: | So Dan and Mary Lou, welcome to the show. |

| Dan Knapp: | Thank you. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Well, thank you. |

| Nick Stumo-Langer: | I’m just wondering if you could just a little bit of a rundown about your history at Urban Ore, and your history in the Berkeley community, and maybe just tell us how you got started. |

| Dan Knapp: | Well, I think the first thing we have to tell you is that Neil got us together. He showed up, and so did I, at the first national meeting of the national recycling coalition in Fresno, California. Afterwards, I was so poor at the time that I hitchhiked over there, and slipped out in the parking lot. Afterwards, Neil said that, “Well, I’ve got a speaking engagement in — in Sacramento, why don’t you come along? They’ve already heard from me. I think your message is more important than mine.”

So without further ado, the two of us jumped on a bus and we went to Sacramento. The next day, I go to get a brown bag lunch, and there was Mary Lou in the audience eating her brown bag lunch. We went home together that night on a bus. There were so many people there from Berkeley that they had chartered a bus. So the two of us got together on the bus. I was so shy that I went and sat by myself, and she came and joined me. So that was nice. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | That’s the most aggressive thing I’ve ever done when I was there. |

| Dan Knapp: | Otherwise it might never have happened. |

| Neil Seldman: | Before you give us the details of how you got from the Berkeley landfill to your current three-acre site in downtown Berkeley, could you just briefly describe the first formal date that you two had at the incineration conference in Berkeley? I think that’s a very charming story. Boy meets girl meets incinerator. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Well, it wasn’t actually an anti-incineration meeting, it was a first time. We had this date. On our big date, he wanted to take me to the city council meeting, which I have not been to city council meetings before. What a treat. |

| Dan Knapp: | What a treat. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | So we went on this big adventure to the Berkeley city council meeting, and we sat in the front row next to each other, and the Berkeley city council that night was voting on whether to move forward with our procurement for a garbage incinerator, a mass burn incinerator. So they were just starting their discussion, and Dan was becoming agitated in the seat next to me, and he said, “But they haven’t heard. They don’t know. They don’t know.”

So they were about to take their vote, and Dan couldn’t stand it anymore. He hadn’t had a chance to comment at all. No public was invited to speak at that moment. So he couldn’t stand it, so he jumped up, and he stood straight up, and he’s 6’1″. So he stood straight up and he raised his arm, and he had his finger in the air, and he said, “Wait, wait! You don’t know. Has anyone told you?” So he’s waving his finger in the air, uninvited to speak, and I’m thinking, “This is my date. What am I doing? What’s he doing?” And so the mayor said, “But there’s no public speaking,” and Dan kept pursuing. “Has anyone told you about the dioxins? Has anyone told you about the ash?” So that night, the city council did end up voting unanimously to move forward with the procurement for a mass burn incinerator. They had not heard all that information, and they had not taken the public comment. In Berkeley, it’s the people’s republic, and they’re supposed to confirm with the public at all times, and they didn’t. Dan Just was upset, and they took their unanimous vote and they moved forward. That was the launching of the incineration opposition. That was our date. I went out with him again anyway. And it turned out to be never a dull moment. |

| Neil Seldman: | The feat of the Berkeley incinerator, and the feat of the Santa Rosa one about a few months before, really started the domino’s falling, because after that within a year, about 30 planned incinerators for California were defeated. So it really was quite a hallmark period. |

| Nick Stumo-Langer: | And it does prove the adaptation of what Neil said. In a recent article saying, “If you study garbage, you will not be unemployed. Also, if you study garbage, you will not be alone.” That’s good for our listeners to know, I think. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Yes, both of those things are totally correct. |

| Neil Seldman: | Well, let me get back to Nick’s first question, and I apologize for interrupting. The story of how you got from the face of the Berkeley landfill, which was the bay, to your current facility. |

| Dan Knapp: | I quit my college professor job a couple years before, and gotten involved in recycling in a disastrous way in Lake County, Oregon, and lost my entire staff and my own job by telling them that this RDF plant, the refuse-derived fuel plant that they had invested in was going to blow up, which it did in the same month as Berkeley voted to start the procurement of that trash burner. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Incinerator. Yeah. |

| Dan Knapp: | So then my only choice really was to do what I did, which was come down here and become a scavenger. That’s how we deal with UrbanOre. The first year we only sold about $150,000 worth of stuff. Though we didn’t have any rent, and our wages were low, so we were a little bit profitable. We were able to invest in things like signage and so on.

Our first capital investment was a $25 sign that said “Drop Metals Here.” Within a week we had an acre of refrigerators, and old dryers, and washers, and all kinds of other stuff, because the public responded right away. They started dropping off all their appliances right there, instead of in the pit where we couldn’t get them. So we learned as we went. By 1983 … I started out at the landfill in ’79. I met Mary Lou in 1980 or ’81. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | ’80. |

| Dan Knapp: | ’80, I guess. Then we started living together after that, and we got married in 1984 in Berkeley, with Neil as the best man, by the way. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Yes, absolutely. |

| Neil Seldman: | Beautiful Rose Garden. |

| Dan Knapp: | Yeah– |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Yes, it was. It was gorgeous. |

| Dan Knapp: | It was really a nice ceremony. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | The city of Berkeley had a municipally owned landfill, which is one of the things that allowed them to give the permission to salvage. And secondly, in the Berkeley 1976 solid waste management plan authored by Ariel Parkinson, and Beth Schikley, and the other people who were on the commission at that time, they had the vision to salvage for reuse.

So Berkeley already had it in its plan that there should be salvaging for reuse at the city owned landfill. This is a very, very, visionary thing to do and provide, and it was contrary to the environmental protection agencies operating instructions for landfills. Their operating instructions were, “Oh, for heaven’s sakes, don’t let anybody salvage at the dump. It’s much too dangerous. You can work at a nuclear power plant or a chemical plant, but salvaging at the dump is too dangerous. Don’t let them do it.” And there was some other reasons as well, but I just wanted to interject that, that’s the reason that Dan was able to come and salvage at the Berkeley dump. The city of Berkeley had already had that vision. So he was emigrating from a place where they didn’t have a vision, to a place where they did have a vision. That’s what allowed UrbanOre to begin at all, because the city of Berkeley allowed salvaging. It was fundamentally incubating the business, because they let these guys go to the tipping face and bring back whatever they could, and put it down behind a fee gate. So from the customer’s perspective, you pay your dump fee, you pay your tipping fee, and then you encounter a recovery and sales area. So people would go to the tipping face and dump, and then they would come back, and they’d stop and buy. But the only people who brought were people who had already paid to dump. So that’s not your biggest market, and not everybody goes to the landfill to shop. So that’s when the small investment that these guys were able to put together, they were able to rent a vacant property. Well, on a busy street, a commercial street in Berkeley. So they rented this empty lot, and they sold their salvaged goods both at the landfill, and then also Dan ran the first, I guess, expansion unit, which was a vacant lot. So he opened that one, and they would provide some of the salvage goods to that new sales area. Then Dan would divert things from getting to … They would salt the inventory with that. Then Dan would divert things from going to the landfill in the first place. |

| Dan Knapp: | And I did that in part by paying people. I developed a tree credit system, among other things, to incentivize people to come to us. I had met a bunch of people, a bunch of haulers out at the dump, and they knew that I had made this transition. So they started coming to me at the new place. So I would usually give them some small amount of money, enough to maybe buy a beer, or buy a sandwich, or something. That was enough to bring them in.

Then I got their stuff, and I could turn around and sell it. We expanded from there. So we were able to move from one place to another as we tried really hard to find stable commercial land to be on. Eventually we did stabilize, and eventually we bought property. Now we sit on a piece of property that we were told last year it’s worth about $9 million. So we own it. |

| Neil Seldman: | Dan and Mary Lou, I know Mary Lou is the operations manager, and I know that Dan is the door specialist. Could you just give the listeners a short description of what you physically have on your three acres? |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Oh, I’m the one with the inventory list. Okay. We have basically everything that doesn’t require a motor vehicle permit. |

| Neil Seldman: | I know the site is three acres. How much do you have under roof? How many square feet under roof? |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | 30,000 square feet under roof. |

| Neil Seldman: | The last time we spoke, about a month or so ago, you have about 35 employees, if I’m not mistaken? |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | About 40. |

| Neil Seldman: | 40. Could you explain how your workers earn money? I know there are various categories of how they could earn money, and I think our listeners would appreciate the way you guys have figured that out. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Well, Dan’s the one who put this compensation together, but I’m the one who explains it most often. Dan’s a sociologist. He constructed this compensation system that is different from anybody else’s. Every person in the company works out on hourly wage, including us. That is so that we are all actually structurally in the same boat. Nobody’s getting rich off of somebody else’s back.

So everybody works on a per-hour wage, and your compensation has two basic parts, really. One is your base wage, and that’s an individual wage. The base wages right now go from 10 and a quarter to 18.50, and where you are in that range depends on your rank, and responsibilities. Nothing depends on longevity. Nothing is seniority. Because you have seniority, that just means you get to keep your job longer. Seniority doesn’t give you anything except for a better share as a profit sharing at the end of the year. On a per-hour basis we have the base wage, and then we have an incentive. The concept of the incentive is that you work for a couple of weeks, and you’ve put out, and you put your energy, and you put out your labor, and you cooperate with everybody, and everybody brings in money. So on the next paycheck, you get some. The per-hour incentive is calculated by taking for that pay period, which runs from the 26th of one months to the 10th of the next month, and you get paid on the 15th. Then the next pay period is the 11th through the 25th, and then you get paid on the 1st. So we get paid twice a month. So for any given pay period, we calculate 9.5% of the gross income. Not including tax. But gross income, 9.5%, and it goes into a pool. Then also, $15 a ton that is salvaged either from the transfer station floor … We still salvage at the dump. 38 years later we’re still salvaging at the dump. We bring in an average of three tons a day with three salvagers. So that’s one ton per day per person they bring in. This is heavy work. They work really hard, and we have a very, very low injury rate. It’s $15 a ton that they salvage, and $15 a ton that the outside trader picks up. It’s a couple of guys in a truck, and we go out and pick things up from people’s homes and businesses when they call us. So they were at six days a week, and the salvagers were at six days a week. So $15 a ton that all these guys bring in, that goes into the incentive pool along with the 9.5% of gross income. Then the incentive pool is divided up by pay period equally according to the numbers of hour you work. Actually, we’ve done very well. In 2017 I think the average was $4.02, or $0.03 per hour for everybody who worked over the course of a year. It fluctuates up and down with income, but it averaged out at the end of the year at about $4.00 and $0.02 or $0.03 cents per hour. The beginning wage is 10 and a quarter, so you add 4 and a couple of cents to that, so that’s $14.27 an hour as the beginning wage. Starting October 1, the minimum wage in Berkeley is going to rise to $15 an hour, so we structure that for October 1. When you work here, you get a base wage and a share of the gross income, it’s incoming sharing, which, of course, is different from profit sharing. You work here, you make money for the company, and you get some on the next paycheck. |

| Nick Stumo-Langer: | That sounds like a really interesting kind of social enterprise model that I think is interesting and goes through a number of the different initiatives at ILSR.

If you’re a regular listener to this podcast, you know that we don’t have any corporate sponsors who pay to put ads on our show. The reason is that our missing at ILSR is to reinvigorate democracy by decentralizing economic power. So it doesn’t make a lot of sense for us to carry ads from these national companies. Instead, we rely on you, our listeners. Your donations not only underwrite this podcast, but also help us produce all of the research and resources we make available for free on our website ilsr.org. Every year ILSR’s small staff help hundreds of communities challenge monopoly power directly, and rebuild their local economies. So please take a minute and go to ilsr.org, and click on the donate page. That’s ilsr.org/donate. If make a donation isn’t something you can do, please consider helping us in other ways. One great thing you can do is to rate and review this podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. Ratings help us reach a wider audience, so it’s hugely helpful when you do that. One other thing you can do is sign up for one of our newsletters and share it with your friends. Now, back to Dan and Mary Lou, co founders of Urban Ore in Berkeley, California. I think for a lot of our listeners, they hear Berkeley, California, they think you see Berkeley, and maybe don’t know a lot about it outside of some activist base. My question is: how does your work at Urban Ore fit in to the local activist movement? It already sounds like you’ve started off this enterprise with some tension with the local government, and the county, and the city council. How was that shaped into what Urban Ore has become? |

| Dan Knapp: | We feel that what we’re part of is something that we’re now trying to extend from the waste managers. We’re still in control in Berkeley, even though we’ve taken away more than half of their market share. By that I mean Berkeley has reduced landfilling as of two years ago by 55%. That means that’s not this funny number that they call diversion, which is full of things that are really not recycling.

This is real stuff. This is really where the railroad meets the road, when you can stop land filling. 56% is how far down we’ve taken garbage in Berkeley over the years, and we’ve done that through six different major materials recovery enterprises. We wrote the zoning law that recognizes materials recovery enterprises as a business site that can exist on light industrial land. We had to do that in order to move to our personal location. We’ve managed to whether all this somehow. We’re still in the midst of it, though, we’re still fighting. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | You have to fight for your life all the time. All the time. |

| Neil Seldman: | We at the institute, and our audience made up of many activists, so we know what you’re talking about. Mary Lou mentioned that you’re still recovering about three tons per day. That’s done at the transfer station, which the city owns, if I’m not mistaken. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Yes. City owned and operated, yes. That’s one of the features of the local system that allows us to operate, because we actually have proposed salvaging at two other places around here, but both of those are private facilities. They’re not municipally owned. And they have unions that won’t let us on the floor for anything.

They’re also got a large corporate parents from Texas, for example. Their lawyers just don’t understand it. They’ve never had experience with it. They think it’s way too dangerous, and they’re not about to let us go salvage things, because they have the same waste management attitudes that Dan was talking about that stopped anything from happening up in Eugene, Oregon. We’re allowed to operate because it’s municipally operated. |

| Neil Seldman: | Dan mentioned that the total waste stream in Berkeley has dropped 55%, which is quite extraordinary. I wanted to point out that UrbanOre is a private company. They are not, of course, responsible for the entire 55%, but they’ve actually been acting like a social enterprise on not only recycling, but many other issues, zoning issues. A lot of money comes out of Urban Ore that is not a business expense, it’s a community expense.

And among the projects that UrbanOre is helping to support now are the recycling archives project. It’s currently housed in the University of Illinois Springfield. It’s a project that the institute in UrbanOre started, but Dan and Mary Lou have really been carrying it along with some other people. Susan Kinsella and Wynne Coplea. But I wanted to point out that the activity of Urban Ore is the best definition of a business neighbor. A neighbor that cares not only about its bottom line, but its workers and the surrounding community. We’re really talking about a unique enterprise. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Neil mentioned that we behave like a social enterprise, and, in fact, we feel like a social enterprise. Right now, Dan and I are the only shareholders in the corporation. We have two steps we’re about to take. One is very easy and short, which is we’re going to transform the corporation from a regular for profit California corporation into a new creation that the state of California and four or five other states have inserted into their corporations code.

And we’re going to become a social benefit corporation. And that means that we will have a statement of purpose, and every year we have to file a statement with the state of California that describes what we did in a previous year to meet our mission goal that we said we were going to have. So we’re going to establish ourselves as a corporation that has a social benefit mission. The second step we’re going to take is we’re going to sell this business to the staff. They’ll become a worker-owned corporation in a slightly different format from some worker-owned co-ops, because the worker ownership co-op will be a shareholder in the for profit benefit corporation. |

| Nick Stumo-Langer: | As we move into the last part of the show, I just have a question about salvaging resources in the local economy, and maybe how they lead to better neighbors, better neighborhoods, maybe more connection. I was wondering if we could just talk a little bit about that, and maybe how you’ve seen the communities in Berkeley grow the more that you see folks coming down to Urban Ore, getting these materials, and helping to rebuild some of these parts of the community that maybe haven’t had as much opportunity as others. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Those are the parts of the community that we work with the very most, I think. One of the secondary economic impacts of our enterprise, we salvage at the dump, so everything that we take off the transfer station floor doesn’t become landfill. So that’s pollution prevention right there. We prevent pollution, and then the stuff we’ve rescued we distribute through retail sales.

So we employ somebody to do that. We employ a salvager, we employ a salesperson, we have also employed somebody to wipe it off and put a price tag on it, and a salesperson takes it on to the display floor and they display it as merchandise. And that transforms trash into treasure right there just by wiping it off and putting a price tag on it, and putting it up for sale, and saying, “Look, it’s merchandise.” That transforms it. Then people come in and they buy it. So we provide low-cost goods to the community that will raise the standard of living for people. If it’s a building product … Say you’ve got an old sash window. The buildings out here in this climate, we don’t have snow, and we don’t have cold that causes shrink swell effect in people’s homes. But we sure have a lot of sun. The sun will kill your cell spacing windows so fast. So people’s cell spacing windows tend to rot out. So if you have an old home, a Victorian, say, and you’ve got a ratted out cell spacing window, you can come to UrbanOre and find a replacement for $35 to $45, rather than having a reproduction made for a couple of hundred. So you get to fix up your home with a low cost window. Now, if you’re a low income person, that means that you will buy the window to fix your house up with, rather than say, “Oh, I can’t afford that. I will let my home continue to deteriorate.” So because we have these kinds of materials available to people with lower incomes, they can retain their property values. They can fix up their properties the way they really want to, and they can retain property value. So for the community, it retains property value. That’s part of our economic impact, is retain property value. We also provide materials for craftspeople to work with, with a handyman who puts that window back into your kitchen for you, or does your kitchen remodel, your bathroom remodel. We provide the materials that they work with. If they buy a window from us that is painted orange with purple polka dots and they’re putting it into a home that’s painted white, they’re going to have to take some time to refinish the window. So they get paid to refinished the window, so that’s adding a little bit to the crafts person’s income. When they put the window back in, it’s an original window. So people who are doing historic preservation, and historic conservation, come in and buy things from us, because we have the original materials, not reproductions. |

| Neil Seldman: | You describing what happens in the general Berkeley community, but can you describe the very neighborhood where your site is located? And what happened since you opened up there to the business community, immediately your neighbors and down the block from where you are? |

| Dan Knapp: | That’s a very good point, because over the years, having moved UrbanOre several times, what I’ve noticed is that wherever we move, somehow or other around us all of a sudden economic development starts happening. Restaurants, for example. Buildings get converted under restaurants. One of the reasons for that is we’re a draw, and people come from sometimes 100 or 200 miles away to shop at our place. [inaudible 00:30:15] they get hungry.And so everybody looks around and they see all these cars parked out here. Our parking lots are totally full most of the time. The outside of our yard has gotten to the point where there’s hardly any parking spaces. All around us, the businesses that were already here have been thriving, because a lot of our customers then go to them. We’ve got a hardwoods place across the street, and another place that makes furniture out of urban trees. They all benefit from our presence, I think, quite a bit. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | The guy who makes furniture out of urban trees, his business quadrupled when we moved in. |

| Dan Knapp: | Yeah. And you see the same phenomenon of the entertainment venues setting up. It happened over on Gilman Street before we moved where we are now, and it’s happened here since we got here. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | We’re sort of like a lichen on the rock. We come in and we start improving the habitat for other small business. |

| Neil Seldman: | This reminds me of another wonderful anecdote. Over the years, I’ve spent a couple of whole days hanging out at Urban Ore, and I was amazed at two things. One, there was a constant flow of people bringing stuff and taking stuff out, and they all had smiles. This was all day long walking through that parking lot. It was quite wonderful.

But then– |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | It keeps us existing. |

| Neil Seldman: | Yes. And then I remember there were two women, I think they were mother and daughter, who came from about 150 miles away, and they had a truck. And that truck they filled up. It was literally things were tied on hanging to the truck.

I asked them, “Did you just buy a big house and you need … ?” And they said, “No.” But they run a secondhand store. So it occurred to me, I didn’t even realize it, that Urban Ore was a supplier to a network of reuse stores throughout the Berkeley region. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Yes. |

| Dan Knapp: | That’s right. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Totally. We have people who have owned their little shops, and they come in here every day looking for something. They take it back to their shop and they fix it up, and they’ll jack up the price two or three times. |

| Dan Knapp: | Mary Lou calls it supply driven retail. Supply driven retail. You just put your finger deftly on the two markets we have. The first one is the supply market, and that’s the people who have things that they want to get rid of. So they’re the suppliers, and they sometimes are buyers, but more often they’re not, because they’re basically interested in getting rid of things. A lot of times they’re leaving the community, or they’ve already left, and they’re just relatives who are getting rid of somebody’s estate, or something like that. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Or they’re downsizing. |

| Dan Knapp: | Then there’s the demand market, and the demand market is all the people that want things and stuff. So they come here, and some of them, they come very habitual. They’re here every single day. They arrive early because they want to be here when the trucks are unloading. They want to be the first ones to see and have the first pick of the litter. |

| Nick Stumo-Langer: | So, we like to end every episode by getting our listeners a chance to go right from this discussion, they’re kind of hearing about you and your work, into something that you’re interested in, or something that is making you think. Could be a reading recommendation, listening, or watching. Just anything that you want to share with our listeners. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | My very first recommendation is to go way into the way back of wisdom in our field, and read E.F. Schumacher’s Small Is Beautiful. Small Is Beautiful. And also, Buddhist Economics- |

| Dan Knapp: | Buddhist Economics. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Or Good Word. Yeah. Read E.F. Schumacher. I think Small Is Beautiful is the most entry-level thing. But the whole philosophy and concept of decentralization and building local community, he is so eloquent, and so holistic in his discussion of all these economics. He is foundational reading. |

| Neil Seldman: | I also want to point out that Mary Lou was the environmental writer for Friends of the Earth for many of years, and for those of you who have access to Friends of the Earth, going back and getting her early articles would be a good source of things. Before Dan makes a recommendation on reading, I want to point out that one of the nice things about this and our other interviews is that people get a sense of 50 years of really good organizing activity, and obviously listening to Dan and Mary Lou, you can get a sense of that.

The project that Dan and Mary Lou, and I, to a lesser extent, have been working on, have actually documented through interviews and many other sources of documentation, the stories of our colleagues over the last 50 years. Gretchen Brewer, wonderful organizer who unfortunately passed away. Mary Appelhof, the same thing. So for those of you who really want to follow this wonderful movement, democratic environmental movement that’s been highly successful, stay in touch with UrbanOre and the institute, and we will be able to guide you to very relevant documents to how this movement got together, and how it’s sustained itself. |

| Dan Knapp: | I’m trying to think, there’s so many things, I read all the time. Paul Dunnett’s book is good. There’s so many things. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | The whole ILSR website. |

| Dan Knapp: | Yeah. |

| Nick Stumo-Langer: | Can’t ask for a better promo than that. |

| Dan Knapp: | And also, I did my very first podcast, and I’d like to just promote it a little bit. If you go to indeepradio.com, I-N-D-E-E-P radio.com, and then just hit the button for podcast, you’ll come up with a podcast for me that’s an hour long. I was interviewed by Angie Coiro, who’s quite a wonderful, professional interviewer. It was been put out over NPR. It’s a pretty interesting podcast, I think, covering quite a lot that we haven’t even talked about here. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | She’s very interesting. That interview is interesting for one thing, because Angie Coiro is not a recycler, she’s just a regular … And she’s not a community activist. She’s just your basic reporter with an environmental bend. Her questions were extremely good. Also targeted for non-technical recycling audiences. So she was real good at getting to a general audience synopsis kind of perspective and stuff. |

| Neil Seldman: | Dan and Mary Lou, thank you so much. Your testimony, if you will, during this podcast really underscores the principles of why the institute’s interested in recycling. It decentralizes the economy, and it takes away the market share from wasters. And you guys have been more than an ideal model for the rest of us, so we really appreciate you being here, and for everything you do. |

| Dan Knapp: | And you’ve been an inspiration to us. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | You sure have, and we’re very honored to be profiled by you guys in particular. |

| Nick Stumo-Langer: | All right, well thank you very much, and I appreciate you being on. |

| Dan Knapp: | Thanks. |

| Mary Lou Van Deventer: | Thanks. |

| Nick Stumo-Langer: | Thank you so much for tuning into this episode of building local power. You can find links to what we discussed today by going to our website ilsr.org and clicking on the show page for this episode. That’s ilsr.org. While you’re there, you can sign up for one or more of our newsletters and connect with us on Facebook and Twitter. Once again, please help us out by rating this podcast and sharing it with your friends. This show is produced by Lisa Gonzales and me, Nick Stumo-Langer. Our theme music is Funk Interlude by Dysfunctional.

The Institute for Local Self-Reliance, I’m Nick Stumo-Langer. I hope you enjoy us again in two weeks for the next episode of Building Local Power. |

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

If you have show ideas or comments, please email us at info@ilsr.org. Also, join the conversation by talking about #BuildingLocalPower on Twitter and Facebook!

Subscribe: iTunes | Android | RSS

Audio Credit: Funk Interlude by Dysfunction_AL Ft: Fourstones – Scomber (Bonus Track). Copyright 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license.

Photo Credit: Russell Mondy via Flickr.

Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and, for monthly updates on our work, sign-up for our ILSR general newsletter.