On Monday, Hillary Clinton gave the first big economic policy speech of her 2016 campaign. Toward the end of it, an audience member interrupted her, asking, “Senator Clinton, will you restore Glass-Steagall?”

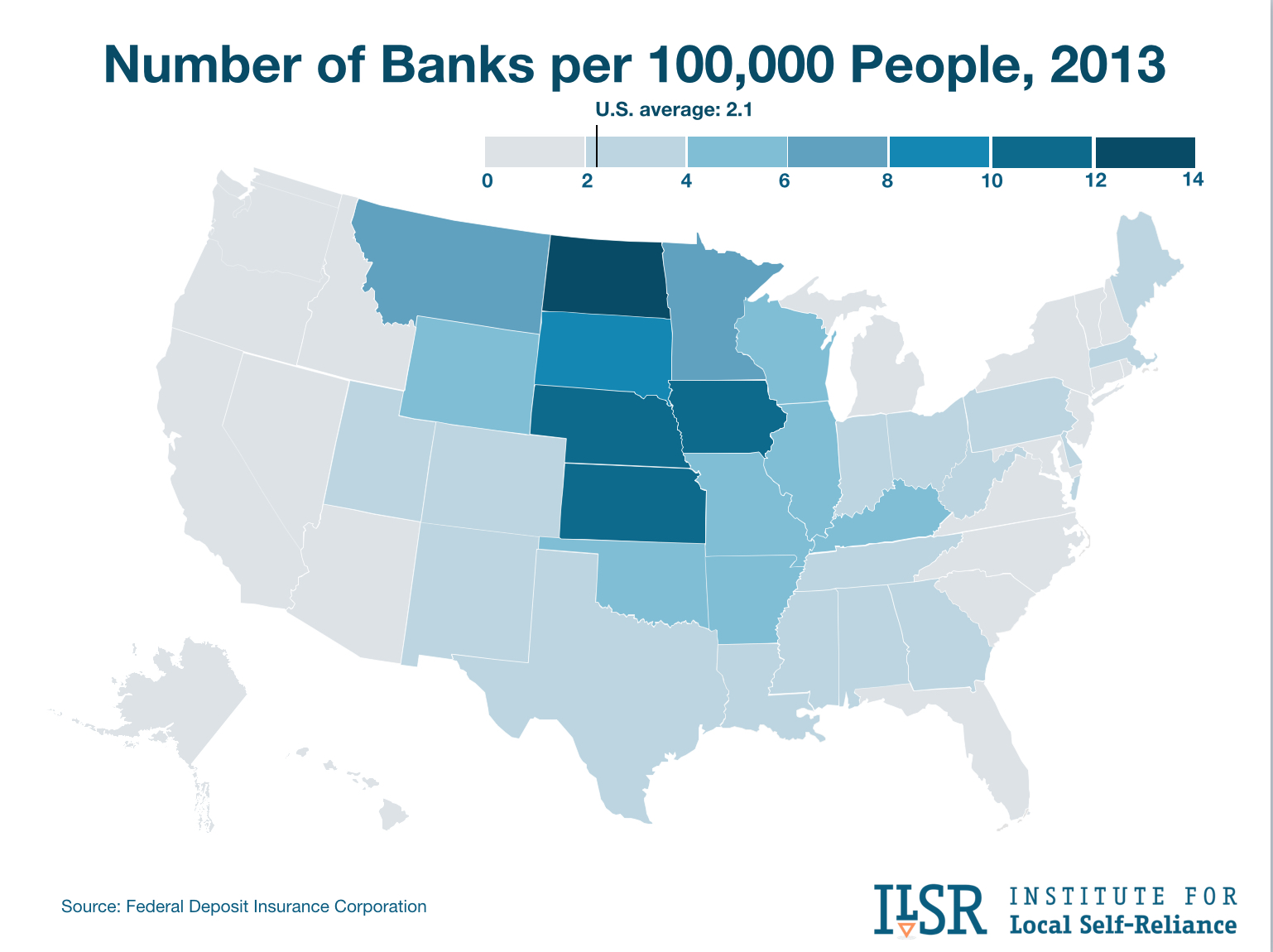

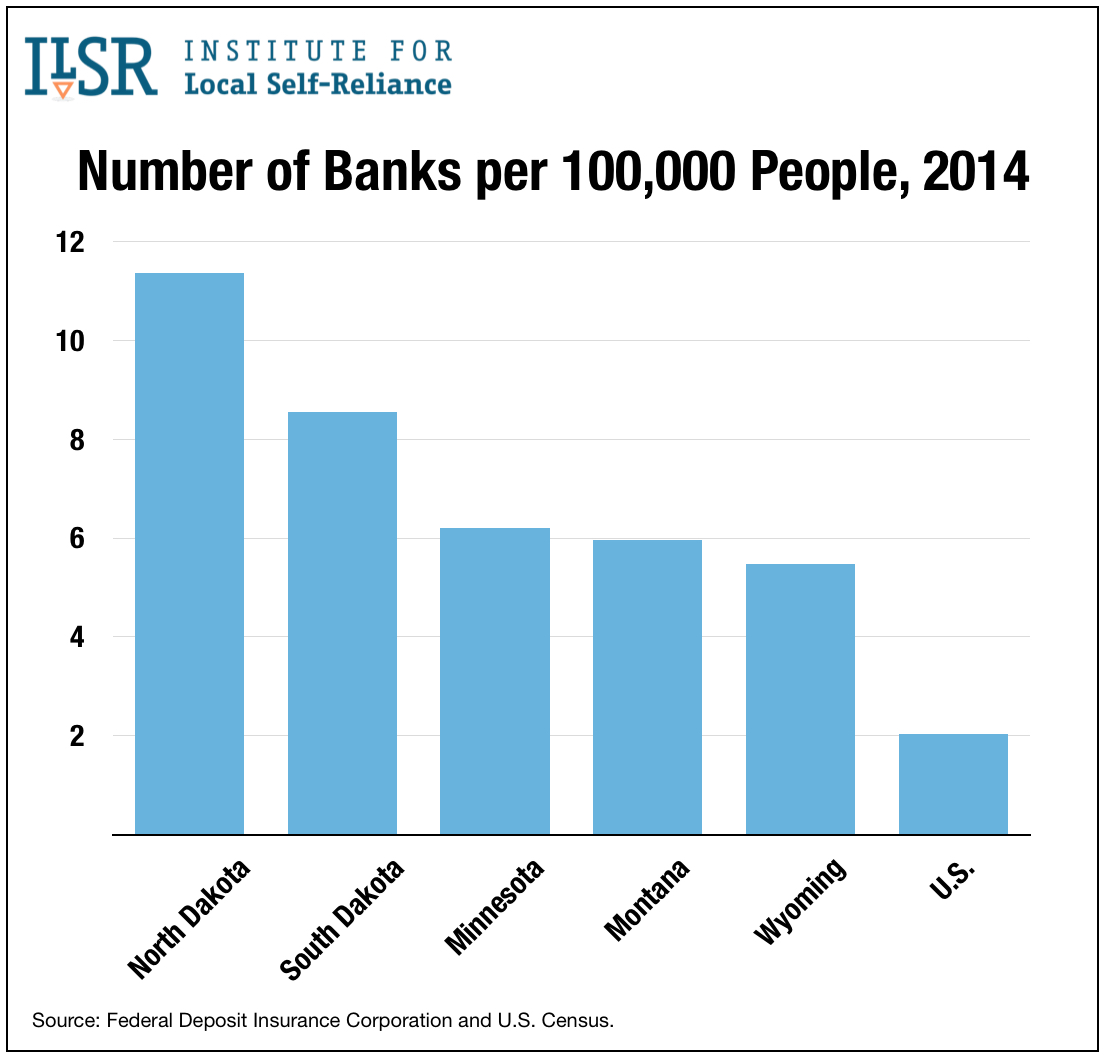

In a campaign season already dominated by candidates’ pursuit of Wall Street donations, how to regulate the banking sector remains one of the most pressing issues facing the country. Seven years after the financial crisis of 2008, the “too big to fail” banks are bigger than ever, while the community banks that make the lion’s share of loans to local entrepreneurs and meet other productive needs are disappearing.

The question that Clinton got on Monday cuts to the center of the debate. In the ongoing push to make our financial system one with less risk, and one that works for more Americans, there’s one policy that we know is effective. It’s the Glass-Steagall Act, a banking reform law passed in 1933, as lawmakers were grappling with the destructive banking activities that caused the Great Depression.

Unlike rules about trading derivatives or risk-weighted capital ratios—rules that, in their complexity, create loopholes for big banks’ fleets of lawyers to exploit—Glass-Steagall, in the course of a mere 37 pages, laid out a series of common-sense reforms. The most central of these was a requirement that investment banks, those that trade securities, be separate from commercial banks, those that accept deposits. In other words, banks swapping subprime mortgage loans couldn’t fund those swaps with a person’s federally-insured life’s savings.

For the rest of the 20th century, Glass-Steagall worked. Then, in 1994, during Bill Clinton’s administration, Congress began picking apart the firewall. In 1999, after years of fierce lobbying by the country’s biggest banks, Congress voted to dismantle Glass-Steagall completely.

Last week, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), along with cosponsors Sen. Angus King (I-Maine) and Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.), introduced legislation to reinstate the heart of Glass-Steagall. “Since core provisions of the Glass-Steagall Act were repealed in 1999, shattering the wall dividing commercial banks and investment banks, a culture of dangerous greed and excessive risk-taking has taken root in the banking world,” said McCain in a statement. “Big Wall Street institutions should be free to engage in transactions with significant risk, but not with federally insured deposits.”

With the 21st Century Glass-Steagall Act, the senators also raised a question similar to the audience member’s on Monday: To what extent will Glass-Steagall be a campaign issue in the 2016 election?

On the Republican side of the presidential race, the crowded field has so far remained quiet on Glass-Steagall. However, as evidenced by McCain’s sponsorship, the issue is a bipartisan one. Even Sen. Richard Shelby, the Alabama Republican who’s now head of the Senate Banking Committee, voted against repeal of Glass-Steagall in 1999.

On the Democratic side, Glass-Steagall is simmering, but Clinton’s challengers are beginning to turn up the heat. There’s Sen. Bernie Sanders, who voted against repeal in 1999, and who’s repeatedly referenced restoring Glass-Steagall as an economic policy priority while on the campaign trail. “Of course I believe in reestablishing Glass-Steagall,” Sanders told the Washington Post. Sanders has also voiced strong support for the Warren-McCain bill, calling the decision to allow commercial banks and investment banks to merge a “huge mistake.”

Martin O’Malley, the former Maryland governor, has made cracking down on Wall Street—and reinstating Glass-Steagall—a central plank of his campaign. Last week he released a 10-page policy proposal on the banking sector, which declares that Glass-Steagall “will be one of his top priorities.” In an interview on Wednesday, O’Malley went further.

“I’m very much in favor of reinstating it,” he said, “and I think that all candidates in both parties are going to be forced to answer that question.”

Then there’s Clinton. She didn’t answer the question about Glass-Steagall in her speech on Monday, and in fact hasn’t yet mentioned the law at all. The policy agenda that she outlined focuses more on issues like regulating hedge funds, and less on sweeping structural reform. Following the speech, however, one of her economic advisers stepped forward to make her position clear. “You’re not going to see Glass-Steagall,” he told Reuters of her platform.

Glass-Steagall is an early, and important, instance of a critical issue on which there’s a split in the Democratic party. It’s exactly the kind of policy rift that campaign seasons exist to delve into. As the debate about how to fix the financial system gets hashed out on the long road to November of 2016, Glass-Steagall should remain a central part of the conversation.

Update, July 30, 2015: In the week following publication of this article, the debate over reinstating Glass-Steagall has intensified. Rick Perry, the former Texas governor and Republican candidate for president, joined the chorus of voices calling for the return of the firewall. In an economic policy speech, Perry included the separation between commercial and investment banks among his proposals for financial reform, saying, “We could again require banks to separate their traditional commercial lending and investment banking and related practices.”

Image of Hillary Clinton by Marc Nozell.