Podcast (composting-for-community): Play in new window | Download | Embed Subscribe: RSS

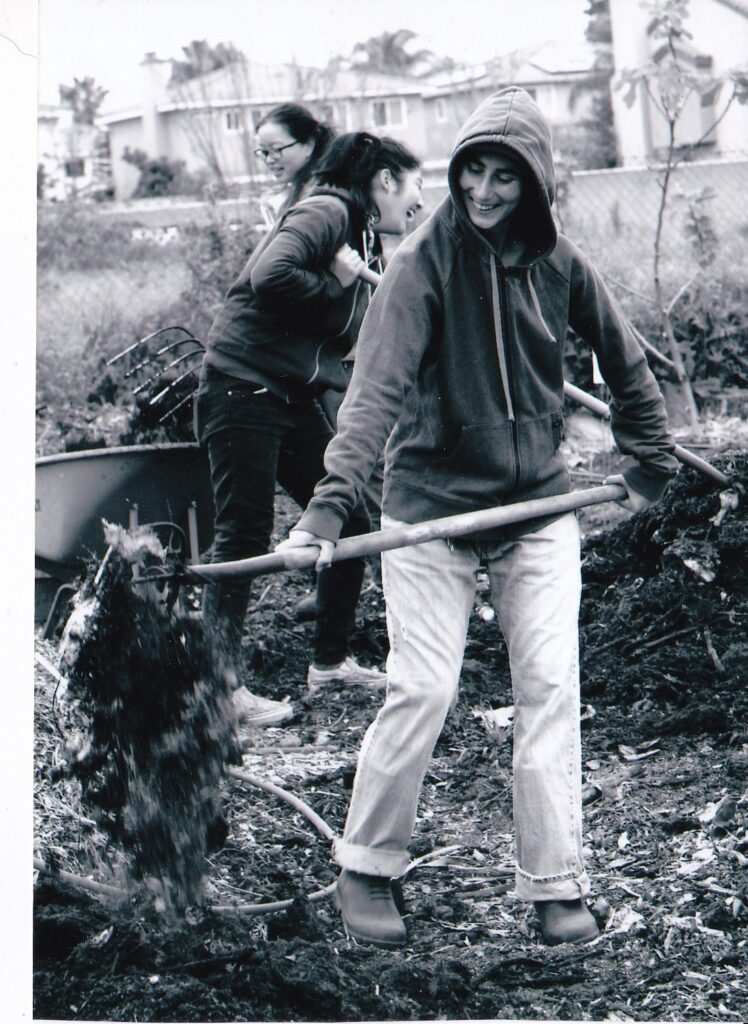

In this episode, host Sophia Hosain is joined by Composting for Community’s intern Alondra Sierra and Elinor Crescenzi, an activist, organizer, and a founding member of the Food Cycle Collective in Pomona, California. Elinor talks about Pomona’s collaborative community composting movement and the power that bike-hauling has to build meaningful connections in the community.

In this episode, host Sophia Hosain is joined by Composting for Community’s intern Alondra Sierra and Elinor Crescenzi, an activist, organizer, and a founding member of the Food Cycle Collective in Pomona, California. Elinor talks about Pomona’s collaborative community composting movement and the power that bike-hauling has to build meaningful connections in the community.

Sophia, Alondra, and Elinor also discuss:

- The intersection of urban farming and waste awareness in the city of Pomona

- How bike-hauling food scraps led to a food rescue program for houseless communities

- The synergy between different community composters and urban farms in Los Angeles

- The need for municipal support for community composting as a movement and service

“Something that has happened a lot in LA Compost and Food Cycle Collective is that we’re actually recognizing that the community part in community composting is just as important, if not more important. And there’s also best practices there, in terms of how you approach other human beings and [the] ways that you build a strong foundation for community.”

Food Cycle Collective Venmo: @PomonaCFA

| Sophia Hosain : | Across the country, the community composting movement is growing. Small scale composting provides communities immediate opportunities for reducing waste, improving local soil, creating jobs, and fighting climate change. You’re listening to the Composting for Community podcast where we’ll bring you stories from the people doing this work on the ground and in the soil. |

| Hi, friends. Welcome back to the Composting for Community Podcast. I’m your host, Sophia Hosain from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s Composting for Community Initiative. Today’s co-host is our fabulous intern Alondra Sierra. In this episode, we’re joined by Eleanor Crescenzi, founding member of the Food Cycle Collective in Pomona, California. Eleanor is an activist and organizer looking at the intersection of composting, community-based food access, zero waste advocacy, and environmental justice. In this episode, we chat with Eleanor about how in just a short time, the Food Cycle Collective has managed to divert 78,000 pounds of food scraps and a quarter of a million pounds of other organics from landfill and incineration. Let’s tune in. Hi everyone. | |

| Alondra Sierra: | Hey. |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | Hey, how are you doing? |

| Sophia Hosain : | I’m so glad to be here with you guys today. I think we can start off. Eleanor, I’m going to hand you the mic. Tell us a little bit about Food Cycle Collective. |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | Great. Food cycle Collective is a grassroots team of about 10 regular folks who do community based composting, bike education, and street level outreach to community members who are currently staying or living in the streets. |

| Sophia Hosain : | Awesome. What are some of the community projects that your members get involved in? |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | So we have three initiatives that kind of take us in different directions. So we try to weave them together. We started out as a community based composting organization, picking up food scraps from local restaurants, from the farmer’s market, taking them to local community gardens, composting them there, building soil from those spaces that were growing food for the community. And through the course of doing that work, we had decided to do it on bikes. We had been really inspired by some work that had been done in Santa Ana with a bike powered youth oriented composting. And we implemented that model. What we found is, as we were riding through the streets, we were noticing a lot of people who were thirsty and hungry and we would be passing by them arriving to a garden and sometimes composting food from the farmer’s market that was looking pretty good. |

| And people were like, “This just doesn’t make any sense.” So we started doing food rescue, preparing that food into meals and distributing those while we were on our way to composting. In the intervening month, we’ve kind of evolved. Now we go on two teams, one still does the food scrap collection and composting and another on the day of our ride, will go out and deliver hygiene items, clothing, food, really just check in on our neighbors who are in the streets, unsheltered, having little access to many necessities. And that’s kind of our rhythm every week. | |

| Alondra Sierra: | Okay. Awesome. Eleanor, for those who are listening, who aren’t familiar with the California landscape, can you give us some context about the city of Pomona and how it fits into the larger community composting movement within Los Angeles county? |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | Sure. So a little bit of historical context about Pomona. Pomona is in Los Angeles county, but all the way on the Eastern border. So kind of far from those urban centers, but it’s a city of about 150,000 people. It’s been a place that’s experienced a lot of historical economic oppression, definitely lots of the city which redlined. Traditionally been a place where people of color have been pushed out of the greater municipal areas of Los Angeles as they were gentrifying. And that led to kind of a history of systemic poverty in this city. It’s also led to maybe some predatory practices by the waste industry. So we have a really high concentration of waste and recycling facilities in the city of Pomona. And that leads to a lot of potential awareness about the impacts of processing waste, about thinking about waste. And so I think that’s something that’s unique about Pomona. |

| Pomona is also historically farming community. So there’s also history of citrus farming and farming. This is in a valley, the Pomona valley is a very rich fertile land. We have this beautiful intersection of awareness about waste and also a lot of farming, a really thriving, urban farming movement here in Pomona. And also a bunch of community composters, both in cycle collective and others. And together, I think we’re really recognizing that we can make change on the level of the city. We do political advocacy to kind of make space for these urban farming projects. And of course a thriving farming system really requires that we restore soil fertility. And that comes in the form of composting. In terms of what’s happening across LA in the state of California right now, the state has started to fund community composting really for the first time. Both with a statewide grant funded through Cal Recycle, the Community Composting for Green Spaces grant. | |

| And of the four core organizers that put forth that program, two of them live here in Pomona. And not only have we seen a great deal of interest in that program that will fund about 130 sites across the state, we’ve had a lot of interest in both Southern California, LA county and inland empire, which is sort of east of LA. And Pomona sits right between those two areas. What we see is outside of the city of Los Angeles, the city of Pomona has the largest number of projects within that program with about nine projects here in Pomona and 13 in the greater Pomona valley. | |

| So almost 10% of the projects that are happening across the state are right here. So we are a little epicenter, a little hub. And what we hope to show is how community composters really can thrive in this dense network that’s collaborative and not competitive. And we see that in our work where one farm has a dump truck, another farm is making a lot of soil. Another farm is just getting, and we’re moving around with volunteers, soil tools to make things happen. And Food Cycle Collective is part of that, kind of connecting the different sites, composting many of them, building soil. And just showing how we are connected and really thrive when we support each other rather than see each other as threats. | |

| Sophia Hosain : | It’s really interesting hearing you talk about kind of the landscape that allows for this kind of collaborative engagement to thrive, like the presence of agriculture, the presence of waste processing facilities. Like the need for solution, homeless populations. I’m curious, you mentioned briefly earlier that you guys operate your business on bicycles. And I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about the bike nature of the work that you do and how that has really brought you closer to the communities that you work in. |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | Yeah, thanks for elevating that. I feel like our bike part gets a little bit of the back burner in dialogue, just because it’s not the first thing that people jump to when they’re thinking of composting. Gardens are sexy, plants are sexy. People want to engage that. And then people are really moved with compassion when they think about folks that are in the community that really benefit from a little bit more care and attention. So I think that those parts of our work kind of get a little bit more attention. But I think it is really the bike powered nature of our work that allowed us to move into caring for members of the community on the street, and also allowing those members of the community to feel more open to participating with us. |

| So what we’ve noticed is when you move on through the community in a bike rather than a car, it slows you down. It keeps you more aware. We notice dumping, we notice empty lots, we notice where people are staying and it’s because of the way we’re moving that slows us down. People see us, they wave at us. They shout out of their car windows at us saying like, “Thank you for what you’re doing.” But we’re really, really visible. So that is partially because we’re moving around in bicycles, in a group with our trailers. What we think is important about that is also really elevating this as a way of moving in the community, being connected to the community while keeping our streets like safe and able to be moved through. | |

| So with this part of our work, we’re also doing things like teaching people about how to fix their bikes. So we hold a popup once a month at the farmer’s market, or we just invite people to bring their bikes and not just fix their bikes for them, but really say, “Hey, this is what’s going on with your bike. This is how you fix it. Here’s where we can get any parts that are needed. These are the tools.” Just kind of knowledge sharing about how to care for your method of transportation. And this also translates really powerfully over into kind of the work with folks in the streets because they often have a flat tire and need a tube, have a bike that they scavenged some parts for, and maybe they’re missing something. And so we’re able to kind of connect with them, see what they need and try to get them connected back to the form of transportation that most of them are using, which is getting around the city on bikes. | |

| Alondra Sierra: | So, one thing that you mentioned earlier is that the Food Cycle Collective gets involved in a lot of mutual aid work, which I think is really important in the city of Pomona. As you mentioned that the city that is faced historically systemic poverty and currently as well. Could you talk to me a bit more about some of that mutual aid work? I know you touched on it just now, but could you elaborate more on that? |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | Yeah, I think it’s like a little bit complex sometimes over time and I think it can be applied at many different levels. I would say that the work in the garden is really more truly mutual aid work, where people are coming together. They’re contributing their labor, they’re growing food for each other. They’re preparing that food. And it’s a way of people with different skill sets, access to economic resources, kind of coming to the table with whatever they have. And we have several gardens that are growing food for the community through a variety of models. And I think some of them such as what’s happening at the Buena Vista community garden are really structured around the more of a mutual aid format. |

| I think popularly right now, people are using mutual aid to refer to all kinds of work that happens with people in the streets where some of it is actually not mutual aid. It is moving across a gradient of resources where some people have resources and other people have very few resources. And I think, to a certain extent, that is true of our work. We are coming with resources and people are taking what they need. And I think that there’s value for that. However, there’s been lots of opportunities for more mutual contribution. And it’s something that our group has talked about quite a bit of how do we call people in? How do we come to the table? What are ways that people can share about their experience that would lead to better policy and better structures that support folks who are really experiencing a lot of vulnerability based on just their living situation. | |

| So we have seen opportunities for contribution like back towards one another. For example, several months ago, there was a large displacement of a community that was living in the streets and we heard about it ahead of time. So we did outreach to the community, got donations for wagons. We brought those to the community members in the street and folks were helping each other through that really difficult time of being sort of quite aggressively pushed out by the police in a space where they had been occupying for many months prior. We tried to collect their stuff and hold onto it for them if they were getting settled. But unfortunately that street then remains patrolled for many months to prevent anyone from coming back to that space. | |

| And it’s been much harder to find community members since then, as they’re dispersed all around the city and not being able to post up anywhere. Not being allowed to put up their tents. So it’s been quite a challenge for folks. And the best way to help people isn’t really clear right now, but we believe that it’s more on the policy level that there needs to be some changes and other resources available to communities living in the streets beyond a homeless shelter. | |

| So our city did receive funds to build kind of a very large homeless shelter, but that’s not a solution for all the people who are living in the street. Some people, they’re not ready for that kind of solution, or it’s not a good fit for them. And so we’d like to see other kinds of solutions, ideally publicly funded it works better for people. And what we recognize is the way that we are moving in the community as Food Cycle Collective does work well for people. We are able to build relationships with people, we’re able to do advocacy. And so there is opportunity for more creative and dynamic solutions. And that’s what we’d like to see and also hear from community members, kind of what their ideas are about what would work well for them. | |

| Sophia Hosain : | I love hearing you talk about the organic way that you all were able to identify a problem and kind of also identify potential solutions right in the same neighborhood. Like food being thrown away at the farmer’s market and people who on the same street are experiencing hunger. And also hearing you talk about the different ways in which everybody can come together to help in ways that they’re comfortable with based on their experience, based on their capacity. And you briefly mentioned earlier that there is a large population of urban farms in the neighborhood and of community composters. And that, I think you said something along the lines of that people can thrive much better in a collaborative rather than competitive environment. And I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about how that plays out with you and your community and how different ways in which y’all are able to kind of bridge the gaps. Whether it be resources or transportation, etc, and kind of work together and come to serve the community’s needs. |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | Well, I guess my belief is that most people really do want to help. And sometimes the reason why they’re not helping is due to a lack of awareness. Sometimes it’s due to just a sense of disempowerment and not knowing what to do. But people like to engage with what we’re doing. We have like a food scrap drop off at the farmer’s market. So we’ve got folks bringing food scraps together to send them to the garden. We have folks who are volunteering to help rescue the food, to cook the food, to distribute the food in the community, to compost the food waste at the gardens. And then of course the gardens are… Putting seeds in the ground, growing food, harvesting it, distributing it. So we have the whole cycle. And when you look at the whole cycle, there’s so many places where people have different skills, abilities, ages can plug in. |

| I think in our culture right now, we tend to really silo people by age, by ability instead of seeing how dynamic is our world and how easy it is to include people in almost anything. And so I think Food Cycle Collective is really dynamic in that way and that it’s doing a lot of different things. It’s able to integrate ideas pretty easily. And we’ve had to ask for a lot of help because we’ve kind of grown beyond the capacity of what one, two, three, four, five, six people can do on their own. And we realize sometimes, we’re not going to have enough people to do all those things that we need to do this week. Like, “Who can we ask for help?” | |

| And we’ve seen in our group, help comes from all different ages of people from the community. We had a group of a few middle school students who needed to do some justice oriented service work. And they wanted to work with people in the community who were living on the streets. And they organized with us for several weeks to [inaudible 00:17:13] build their own trailers and kind of doing outreach in LA, provide food for us about once a month as like one of the teams that are preparing food. They got hygiene packs and things. Though they’re not coming on the ride as much anymore. | |

| And we also have community members who are, who elders, one of the e-bikes that’s been loaned to us right now belongs to one of the elders in the community. And she’s not able to come on the ride all the time but she’s letting us use this resource that she has. It makes our work easier for hauling. So there’s ways for everyone to contribute. And I think it’s about empowering folks that they can be part of this movement and they can be part of the solution. It doesn’t matter who you are or what you bring to the table. What you bring is valuable. And it’s part of the whole. | |

| Alondra Sierra: | It’s interesting to hear you talk about the unity of community composting within Los Angeles. Because this actually takes me back to one of Composting for Community’s earlier podcast episodes that featured Michael Martinez from LA Composts. And in that episode, he echoes this similar sentiment of collaboration amongst members and amongst other organizations spanning the LA composting and sustainability spaces. Can you tell me more about this joint effort between Food Cycle Collective and organizations like LA compost? |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | It’s great that you mentioned LA compost. LA compost has grown so much. And I feel like LA compost has big brother energy towards Food Cycle Collective. Our first trailers are actually LA composts’, old donated trailers that they weren’t able to use anymore because they got originally shut down as a bike calling collective and they were just sort of sitting around. And I actually worked for LA compost as one of my paid jobs. And the trailers were sitting outside the front door and I’m like, “Hey Michael.” “Hi, Alondra.” And he’s like, “Yeah.” And that was kind of the first Food Cycle Collective trailer. Since then, Food Cycle Collective has taught itself how to weld and started building our own trailers. So that’s kind of cool. But in thinking about LA compost and some of the work that we do organizing together at the state level, it makes me want to like elevate… |

| It’s kind of like one of the insights around community composting. We typically, in the community composting space, are always focused on like teaching people how to compost better. How to improve their compost methodology and really focusing on these best practices for [inaudible 00:19:53] decomposition. And that tends to get like a lot of attention in community composting spaces. But something, I think that’s happened very much within LA compost and then worked in Food Cycle Collective is that we’re actually recognizing that community part in community composting is just as important, if not more important. And there’s also best practices there in terms of how do you approach other human beings. And like what are the ways that you build a strong foundation for community? | |

| What are the ways of approaching each other? How do you build high trust? And I think that different ways of moving in the community, different sorts of attitudes actually promote and strengthens the community element in community composting. And those are the movements that really become highly successful and impactful. So that’s also just something to elevate for folks who are listening, who are really into composting, just the recognition that this is a super important part of what we do. And it’s also a place where we can put time and intention to grow. | |

| Alondra Sierra: | I think it’s really interesting to hear you talk about the unity in community composing within Los Angeles county because one of Composting for Community podcasts’ first episodes was with Michael Martinez, LA compost. And he echoed similar sentiments of unity of different participants within the community, different skills coming together, working together, sharing resources. So it’s beautiful that although that episode was back in 2019, which seems so long ago, but really wasn’t, it’s beautiful to know that, that sentiment is still echoed in the work today. So I’m curious, Eleanor, about how the Food Cycle Collective started. I know it began early last year, kind of near the beginning of the pandemic. Was the pandemic a step back for setting a community composting project, or what was that like? |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | I guess the origins of Food Cycle Collective are in a project that was hosted at the now Buena Vista community garden. That group had organized to submit grant application to the Cal EPA environmental justice fund. And in that have been proposed this bike powered food scrape [inaudible 00:22:12] and composting program. But none of the people who were organizing in that group actually really wanted to take this part forward. So someone volunteered to do it, they didn’t work on it for six months. Then a different person volunteered to do it and they didn’t work on it for six months. |

| And then a student who was completing his masters at Cali Poly, Pomona in regenerative studies was like, “I need an internship.” And he came to me kind of asking about it. It’s like, “There’s this project. Would you be interested in doing it?” And was like, “Yeah, I would.” And he happened to have an e-bike. Incidentally, his housemates were also into biking. And I had asked that person previously, because they had been hosting a bike fix it pop up at the farmer’s market and they would be interested. | |

| And they were like, “Yeah, I’m totally interested.” But they were working like 50 hours a week. Some things changed up. They all had left their jobs right at the beginning of the pandemic and kind of the two of them really started the bike power collection of food scraps and started meeting once a week to be like, “What is this?” Kind of generated the name of Food Cycle Collective together. And that was really the beginning of Food Cycle Collective. Then we collected food scraps, bike powered methodologies for… It’s not much March until maybe June of last year. And it was in the summer when it was really hot, where we started to shift our work into really supporting folks who were living in the street. And it started with water. Riding around in the heat as a group. And just seeing people really struggling with the heat. | |

| And then someone was like, “Hey, we should at least be passing out water.” So buying water and passing it out and then composting the food scraps as I mentioned before. And being like, “This doesn’t make sense. We’ve just been passing out water to folks who are probably also hungry.” And so then that was how food rescue was born. In terms of the pandemic, the spaces that we were moving in were all spaces that I think were particularly impacted by the restrictions that were imposed by the pandemic. We were riding bikes around the main place. We were interacting for food rescues at the farmer’s market, which is a place that remained sort of untouched by the shutdown. And then interacting in community gardens, which were also outdoor spaces. So we were able to grow pretty easily. Maybe in some ways there was less volunteers available, but in other ways, some of the people had the motivation to volunteer, maybe had a little bit more free and then they might have otherwise to work on the project. | |

| So we’ve been distributing food and water in this way for over a year and continue to compost food scraps at the gardens. We work with several different gardens. We have them on a rotation doing different gardens each week in the city. And I think that in general, the pandemic on a macro level has kind of helped people realize some of the things that are really important. Community, your food system, being outside or all things that have kind of been highlighted. And a lot of people have had more space for reflection where they haven’t been driving to work or commuting about what is the life that they really want to live. And I think that’s brought some really solid community volunteers and energy to the work that we’re doing. Which may not have happened if people were just kind of doing their business as usual status quo, pre-pandemic lifestyle. | |

| Sophia Hosain : | And also, it seems like the pandemic did create space for you to do this work in some ways. People had opportunities or time that they didn’t have to, or realized things were more important than what was really important. But also, the populations that you serve, particularly the people who live in the streets are not born from the pandemic, right? Homelessness is an epidemic that precedes COVID-19. And so I think it’s really awesome that you all were able to just fold it in to the work that you do in like a very natural and seamless way. And so I’m wondering, I know that you mentioned policy as potentially being really important in the path forward. What do you see next for the movement? Is there any policy that you’re working on right now? Are there any grants that you’re going after? What’s the vision? |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | We’ve had been having a lot of dialogues about how do we engage our local city council in kind of truly more compassionate interaction with individuals who live in the street. Our city recently in the past couple years, adopted a charter of compassion. So I think it’s been like a word that’s really leveraging with the community. Because our experience is that the treatment of the folks who are living in the streets from institutional engagement has been really embodied with compassion. So we’d like to see something different. And so far we just opened with more informal dialogues with city council members and then really looking to kind of develop something more formal, I think, over the next year. We don’t have a solid game plan at this particular moment in time. I think it’s just an awareness that we need to come together and really propose different solutions. Alternative solutions, ones that will work for folks who are currently not really receiving any meaningful assistance or engagement from the city. |

| On the composting side, we would love to see community composting be fully recognized as a viable, meaningful, productive, generative way of addressing the organic materials. We think of them now as waste, but hopefully really shifting that perspective to really seeing them as that’s the restored soil fertility for these projects. And that community members can really take urgency over what happens to those. They can ensure that they’re delivered back to local soils and that this is an important way that human beings in our community can engage with these resources and steward them. | |

| So what we would like to see as the state pushes the cities to ensuring that those materials don’t end up in the landfill, that our city doesn’t just do what so many other cities are doing in saying, “Oh, we need to find a big waste hauler to truck this out many hundreds of miles from where we live to turn it into compost that really may never return to our soils and might not actually be a very good quality.” Instead say, “No, we really see that local composting is one of the highest and best uses for these materials and we want to support our local businesses and stewarding these resources back into our local gardens, which are providing food security and beautiful green space is gathering spaces, park spaces for our community. | |

| And really have the city make space for the development of community composting as a movement, but also as a service that exists in our community. And to really encourage the city to hold space for that. We want our community composers to be processing 25% of the waste that’s generated in the city and reclaiming it as the resource that’s needed to grow food for our community, instead of saying, “Yeah.” Whatever you can do on the side, that’s cute. Like you can do that being like, “No, we want to support this initiative. And we want to make sure that our community has access to these kinds of dynamic community engaged programs. | |

| Because Food Cycle Collective is something that community members can get involved in and be a part of and traditional waste hauling isn’t. And so we want the community benefits that come from community composting to be recognized at the municipal level and advocated for at the municipal level, through actual action and programming and necessary regulation. | |

| Sophia Hosain : | I love it. For our listeners who are with us today, if they want to support you, if they want to support Food Cycle Collective, are there any concrete ways right now? Do you guys have any crowd funding campaigns going on right now or is there other ways that our listeners might be able to support these efforts? |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | Well, yes. Always. I think if you’re local to the area, we’d love to see you join us. We currently ride on Sundays. We gather at like 12:30 in Lincoln park and then move through our community for the next several hours. Composting and doing street level outreach. So we’d love to see your face. We’d love to have you participate. In terms of funding, we are always in need of funds. This is mainly a self-funded initiative from community members who are involved in a few donations that we’ve received. Sometimes we need to be responsive to the needs of community members, whether that’s buying bike parts or new bicycles. Or we weren’t able to get a donation of water or other averages, hygiene items. So we do accept donations directly, water and other items at farmer’s market, which is on Saturday morning. You can also bring your food scraps there and we would love to help those go into the community. |

| And for folks who are involved there, we ask folks to engage with us in a committed way since we’re engaging with the community in a committed way. We invite people into partnership with us in one of three ways. One is by making a volunteer commitment to supporting these kinds of community based food systems work. We ask people to be in a mutual benefit relationship where we maybe we’re helping you with your food scraps and maybe you’re a restaurant and you’re donating food other necessary items to us or in financial partnership. We do have some upcoming needs. We are trying to grow and we need new e-bikes, our main e-bikes that started us out just have gone to the happy rolling grounds. | |

| And so we are in need of new e-bikes. So we’d love to collect donations for that. You can shoot us some funds on Venmo through our partner at the Pomona Community farm Alliance. So @PomonaCFA, just put in the notes that I don’t know if that’s a donation for e-bike or Food Cycle Collective, and we would love to receive that and turn dollars into tools that are needed for our community action. So really, anyway that folks are able to contribute. We’re interested in elevating contribution as a way of engagement and commitment. So we’re committed to the community and that’s really all we ask for from our surrounding communities to also be committed to these kinds of initiatives and to the community as a whole. | |

| Alondra Sierra: | Awesome. So if you’re in LA county or specifically in Pomona, please get involved. And Eleanor, as we wrap up this episode on the Food Cycle Collective and on community composting in Pomona, I want to make sure I ask you. Is there anything else you would like to share for those listening? |

| Eleanor Crescen…: | So much, but I think the reality is, for me, I would give the message of empowerment to folks in the community. Like a Food Cycle Collective is something that anyone could start in their own community. It doesn’t require a lot of resources to get up and running. We are even able to do things by pedal power. We often do that when our e-bikes break down. So it’s something that requires very little kind of startup resources relative to other projects. It’s something that one or two people can engage a group of friends and just start making impacts in your community. In general, community gardens need support building soil, something that a lot of people maybe don’t know much about. So for folks who are interested in composting, that’s a way to elevate those efforts. Maybe you’re great at backyard composting, but composting is a lot more fun and even more meaningful when you do it in community. |

| So I would encourage people to take things up a level if you’re already composting and reach out to the local community gardens. It’s a spot that often needs help. And just find a friend who’s willing to maybe do something together with you or just put yourself out there as someone who’s willing to make these contributions. That’s how we start to build the world that we want to live in. If we’re going to wait for someone else to build it, we’re going to get more capitalism and more hierarchy and more of what we already have. It’s up to us to really look at what we know and the creativity we have and the problems that are in front of us and kind of take some initiative towards enduring action that builds something else. | |

| So I would like to encourage people, if you have an idea for something small, just start. You can make big changes in your community and they really can impact other people in ways that are positive and transformative. So, go for it. | |

| Sophia Hosain : | I am certainly feeling very inspired by our conversation this morning. And I hope that all of our readers are feeling inspired too. Oh sorry, our listeners. But if you would like to read about the Food Cycle Collective or to access some of the links and resources that were shared in today’s episode, we will be creating a website landing page type of feature thing. Like a Food Cycle Collective Instagram page, or Venmo, a little bit more information about Eleanor and their radical work. |

| So Eleanor, thank you so much for joining us today. It’s been a super inspiring and fun conversation to have with you. I’m really glad that we’re able to share the story of the Food Cycle Collective with our listeners. And with that, we’ll see you next time. This has been the Composting for Community podcast. Take care everyone. | |

| Thanks so much for listening to this episode of the Composting for Community podcast from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. We’ll be back again next month with the new episode. Our theme music is, I don’t know, from Grapes. Be sure to check out the rest of the ILSR podcast family, including building local power, local energy rules and community broadband bits at Ilsr.org. |

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | RSS

Listen to this episode, then check out more episodes of the Composting for Community Podcast.

Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and Instagram. For monthly updates on our work, sign up for our ILSR general newsletter.

If you have show ideas or comments, please email us at info@ilsr.org.

Audio Credit: I Dunno by Grapes. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license.

Image Credit: Elinor Crescenzi