Randy Wilson knew you had to start somewhere.

Knocking on doors and hanging around retail store parking lots, he and volunteers from the citizen group Kentuckians for the Commonwealth collected signatures. After weeks of holding out clipboards, they collected the more than 500 signatures needed to run for the board of the Jackson Energy Cooperative in Appalachian Kentucky.

It was unprecedented for Wilson in 2009 to challenge a sitting board member. Never in the cooperative’s 71-year history had a board member run opposed.

“The conversation needed to be had,” says Wilson, a folk musician, educator and first-time politician. His picture turned up on the front page of the newspaper. His voice reverberated on the local radio show. He spoke to his platform of financing energy efficiency improvements on the electricity bill (known in energy policy circles as on-bill financing), and moving the local economy past its dependency on coal to alternative energy sources like solar.

Wilson notes that he had a challenge getting his message to resonate with the cooperative’s membership.

“People didn’t say anything about, ‘We gotta save our coal miners,’” he says. “They never said that, nor did they say anything about the environment. Not neither of those was on their mind. The only thing on their mind was that damned electric bill.”

The cooperative’s annual meeting, where the election for board of directors was held, was more of a festival, so as to encourage participation. Cooperative member-owners dished up plates of food. A band played gospel music. Teenagers accepted scholarships for college. Co-op staff passed out energy-efficient light bulbs. An antique car show revved up with almost a hundred participants. A skydiver jumped out overhead with one of the world’s largest American flags trailing behind him. Civil war re-creators fired off cannons.

At the end, Wilson wasn’t surprised that he lost the election 740 votes to 151. Less than two percent of members turned out to vote. But the use of “proxy” votes made a huge impression on him. Mostly used at corporate shareholder meetings, proxy votes allow one member to delegate his or her voting ability to another member. In the case of Wilson and Jackson Energy, the electric cooperative had collected hundreds of proxy votes from its members, then handed them to other members present at the meeting, telling them to vote as they saw fit (meaning, for the incumbent).

There’s no blame in Wilson’s voice, only laughter. He knows the cooperative’s board of directors was scared.

“It was all new to them,” says Wilson about the election. “Nobody had really spoken. It had all been cut and dry before.”

The Roots of Democracy

Incumbents running unopposed, questionable election procedures, low turnout: for many cooperatives, Wilson’s story is not unusual.

It wasn’t always this way. Conceived during the violent winds of the Great Depression and Dust Bowl, electric cooperatives — like many other rural cooperatives — were a way for rural people to band together and better their lives. Formed from five-dollar contributions from prospective members, electric cooperatives went where investor-owned utilities wouldn’t, stringing wires into the rural and rustic corners of America. With cooperatives, profits don’t go to distant shareholders. They go to local members, who own the very business that sells them electricity.

Today, there are some 900 electric cooperatives serving 13 percent of the population, and span about three-quarters of the nation’s land.

With democratic control, cooperatives have the potential to be very responsive to member interests. Roanoke Electric Cooperative (REC) in North Carolina recently undertook an on-bill financing program to help their low-income members save energy and money while paying for energy efficiency measures on their monthly bills (what Randy Wilson was proposing for his cooperative). Farmer’s Electric Cooperative (FEC) in Iowa employs more solar energy per capita than other utility in the nation. The Kauai Island Utility Cooperative (KIUC) in Hawai’i guided the cooperative to attain close to 40 percent of its energy from renewable resources while stabilizing sky-high electric rates.

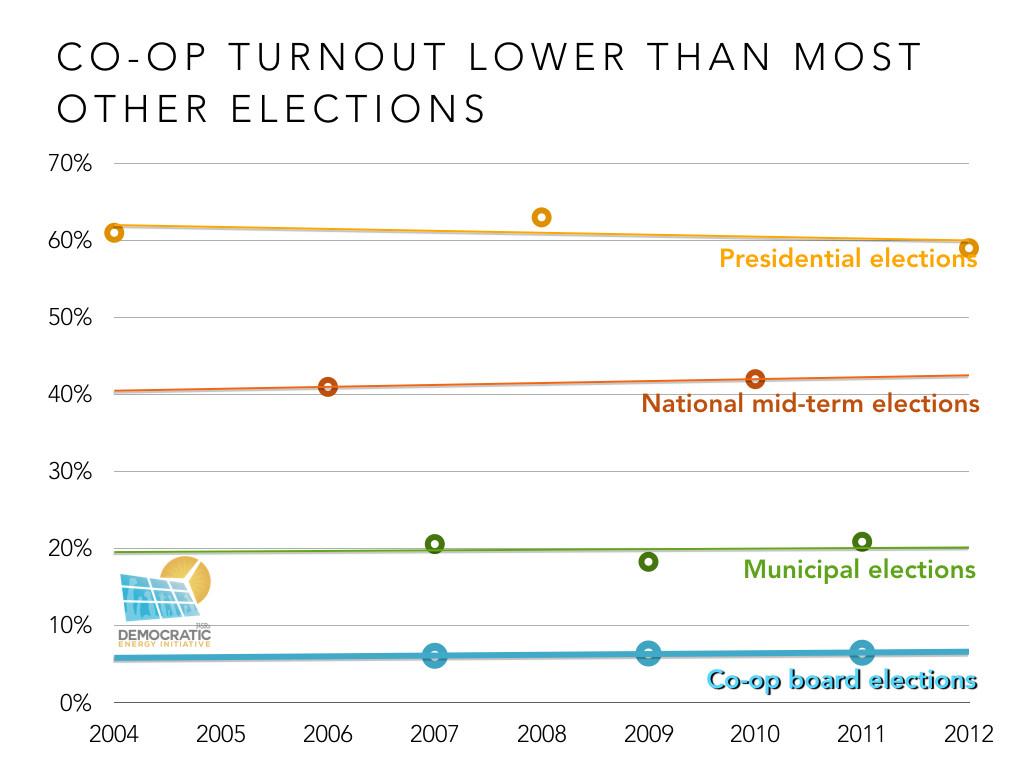

But even for these progressive cooperatives, voter turnout ranges from not-so-good to not-good-at-all, according to voting data acquired from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. From 2006 to 2011:

- Roanoke member-owners voted for their board with an average turnout of 4 percent;

- 17 percent of member-owners turned-out for Farmer’s Electric board elections;

- Kauai maintained a 31 percent voter turnout, among the highest rates in the nation.

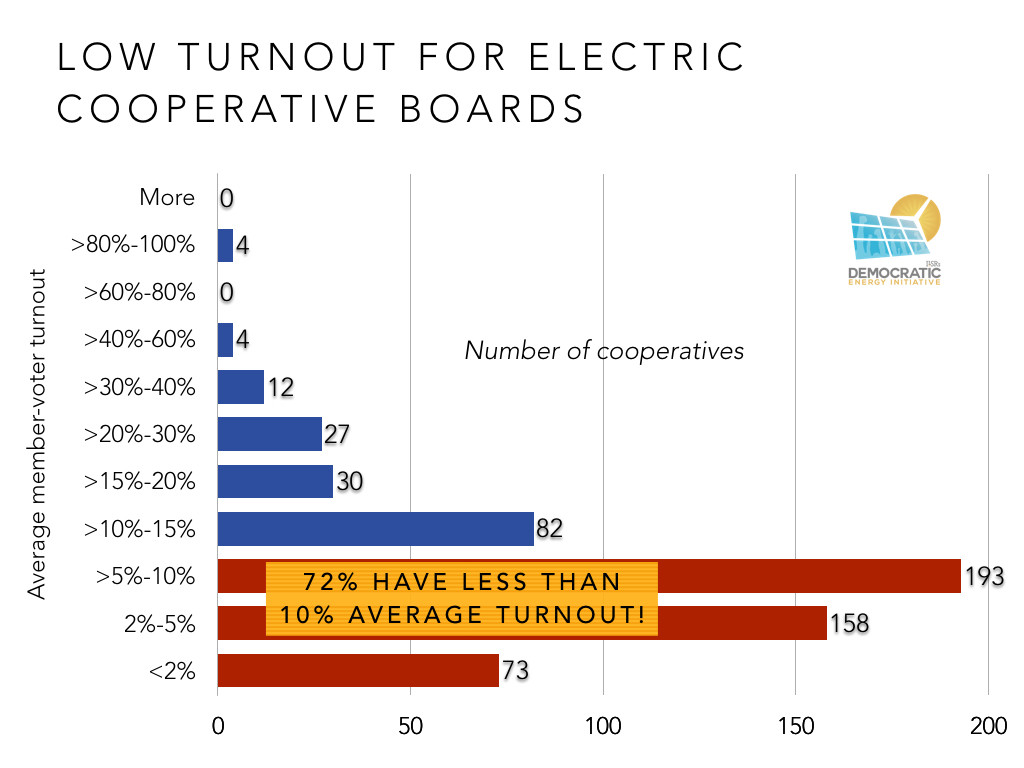

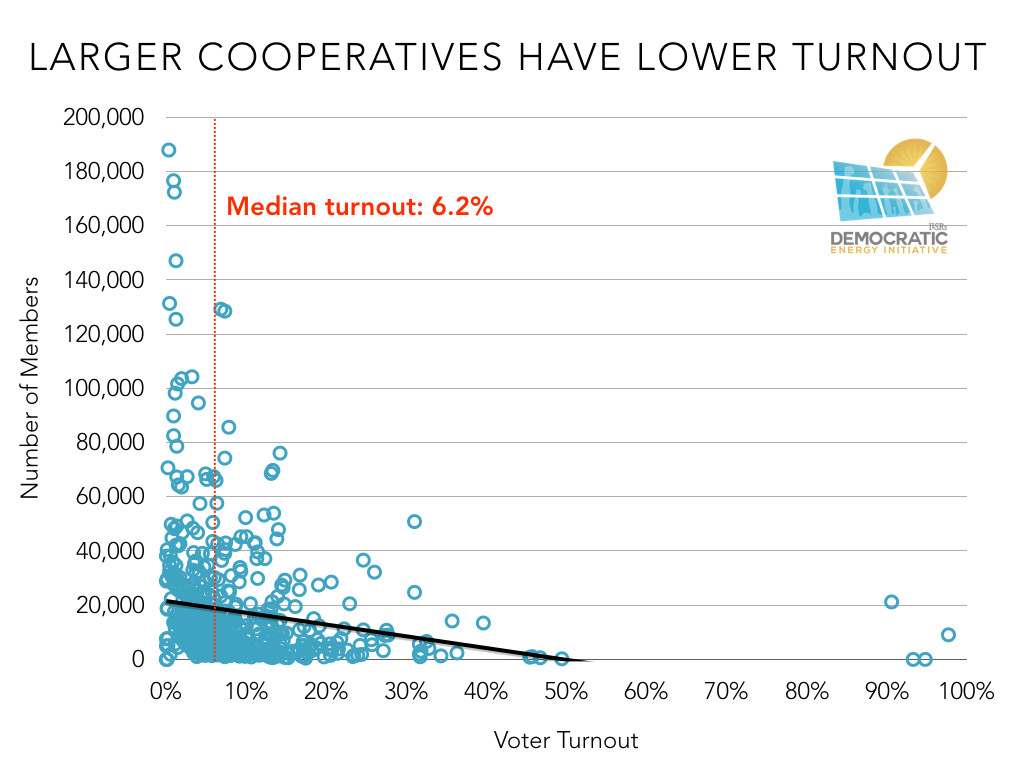

In all, according to research from ILSR, more than 70 percent of cooperatives have voter turnouts of less than 10 percent (including Wilson’s Jackson Energy Cooperative, which averages just under 3 percent turnout).

Low member turnouts come at a harrowing time for electric cooperatives and the energy industry. Electric sales are stagnating. Distributed energy such as rooftop solar is becoming cheaper and more pervasive. Electric cooperatives, mostly dependent on coal for power, will face higher costs from the Obama Administration’s Clean Power Plan if they attempt to hew to the status quo.

Assuming Ignorance (or Apathy)

The low turnout for cooperative elections could be lumped with historically lower turnout in federal election turnouts. Municipal election turnouts are even worse, according to a University of Wisconsin study. But compared to both of these, electric cooperative voting rates are still low.

Rory McIlmoil, a Blue Ridge Electric Membership Corporation member-owner and energy policy director at Appalachian Voices, says cooperative members usually don’t play an active role in utility affairs. He suspects it’s “mostly due to the fact the co-op members don’t quite understand what their rights and responsibilities are as member-owners of the utility.”

Typically, jobs and families come before bill savings and energy policy. Co-op members really only get involved when it hits them at home, and hits them hard.

Jan TenBruggencate, the board chair of the Kauai Island Utility Cooperative, says that interest and turnout spikes when electricity prices are too high, or there’s a contentious issue. The utility’s turnouts—almost the highest among cooperatives—run from the low 20s to 43 percent, but KIUC’s own surveys suggest that more co-op members claim to have voted than actually do.

“As board members, it would be convenient to believe that turnout is low because people believe we’re doing a good job,” he wrote in an email. “Another option is that turnout is low because folks are frustrated and don’t feel they can make a difference. Or that they simply don’t understand the mechanics of the utility business and don’t feel competent to select a candidate. Or perhaps candidates don’t do enough to distinguish themselves. Lots of possibilities.”

Geography further worsens the matter of cooperative-member connection. Small, remote cooperatives such as KIUC or those in Alaska typically have higher voter turnout, in the 20 to 30 percent range, while those focused around populated metropolitan areas tend to have lower turnouts, often lower than five percent.

Many electric cooperatives, started to serve rural areas, now serve growing, spread-out swaths of suburbs. Many members don’t even know they are members. One cooperative organizer (preferring to be anonymous) suggests that voting rates aren’t that much different from other credit unions and other cooperatives, such as REI or Land O’Lakes.

“The trend seems to be,” the organizer continued in an email, “the less important co-ops make themselves [relevant] to their constituents’ understandings of their lives and their interests, the less likely those members will vote or engage with the co-op outside of the commodity transactions.”

In all, according to research from the Filene Research Institute and others, only one to five percent of worldwide cooperative members participate by voting in their cooperative elections.

An Alternative Explanation: Malicious Intent

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, several electric cooperatives in the South suppressed voter turnout, gouged members with high electric rates, and abused their power. The Co-op Democracy Project organized against them, helping to empower a mostly black membership to gain seats on mostly white boards of directors. The group had some success, but the anchors of local incumbency, burdened with difficult-to-access meetings, elections, and voting requirements, were often too heavy for members to lift. From the link above:

“[Electric cooperative] boards perpetuated their rule by manipulating election bylaws and by using co-op resources to gather proxy votes and ballots for themselves — sometimes offering green stamps or even cash prizes in return for proxies. No one, not even [Rural Utilities Service, the federal funder of electric cooperatives] officials in Washington, appeared willing to stop them. Unchallenged, with co-op members purportedly uninterested in operations, these men simply reappointed themselves year after year.”

Since then, the political process at most electric cooperatives remains unchanged. Nominating committees made of board-nominated members still act as arbiters for candidates to run for the board. Proxy voting is still used among some electric cooperatives (though, according to anecdotes, not in food cooperatives or credit unions). These detours add to a sometimes tortuous nomination and election process, full of obscure waiting times and petition requirements, that allow the utility and its board to swing votes toward incumbents. The graphic below explains the process, also shown in the text underneath the graphic.

So you want to run for your electric cooperative’s board of directors? Following these steps might not be so easy.

- Step 1: Review your electric cooperative’s bylaws. These contain the election information you need. But even in the digital age, co-op bylaws can sometimes be hard to find online.

- Step 2: Find out if board of director seats are open in your region. District maps might not be available or current, as one Kentuckians for the Commonwealth member found out. His cooperative told him he no longer lived in the open-seat district. After the election was held, the district maps reverted back, placing him within the district he had supposedly not been in.

- Step 3: Get on the ballot. Usually, current directors make a nominating committee of other members to nominate candidates to recruit or choose from a pool of applications. The nominating committees act as arbiters of candidates, acting within an obtuse range of dates. Petitions can bypass these committees, but the amount of signatures needed varies significantly by cooperative. St. Croix Electric Cooperative requires only 15 signatures about a month before election, whereas Shenandoah Valley Electric Cooperative requires 250 signatures. Other cooperatives have and do require more.

- Step 4: Get your name out. You have to reach co-op members, many who don’t realize they have a vote at all. As Randy Wilson’s election run showed, it can be difficult running against an incumbent with strong community ties.

- Step 5: Hope for votes at the annual meeting. Some cooperatives only vote by mail. Some break ties by flipping a coin. Others employ a variety of voting methods. But beware the proxy vote, whereby members (or appointed committees) can apportion votes how they see fit.

The use of proxies may explain Missouri’s Citizen’s Electric Corporation, which had turnout regularly above 90 percent in our data, more than double the next highest. Its cooperative policy brings a clue. If a member has ever used a proxy voter ballot (to allow a board member to vote on their behalf), but didn’t return a ballot in the current election, a board committee is empowered to cast a vote in their name. The member, therefore, may have her vote cast without her express permission.

When carried to extremes, these policies have resulted in the worst cases of electric cooperative abuse. Un-democratic cooperative boards have allowed paid managers to run effectively unchecked. At Choctaw Electric Cooperative in Oklahoma, the board of trustees raised member bills by as much as $150 per year, gave the CEO a gift of $2.1 million and allowed him to use cooperative heavy equipment for personal use. With a highly compensated board, the former CEO of the Cobb Electric Membership Cooperative in Georgia defrauded his cooperative out of millions of dollars to fund his own side-businesses and a proposed coal plant. Since 2009, at least 14 lawsuits have been brought against 12 other electric cooperatives that have failed to refund capital credits to their members.

But more than the prevention of the occasional, heinous scandal, electric cooperatives are simply in need of new blood to bring the cooperative up-to-date with current energy industry trends. Board members are usually old, white, and male, with incumbencies that stretch back years if not decades. Their jobs are usually less than half-time but pay anywhere from a few thousand dollars to more than $50,000 per year. That money is often a huge difference for rural places often without much other opportunity. Some folks simply want the job for pay and prestige of running an institution that serves as a cornerstone of the local community.

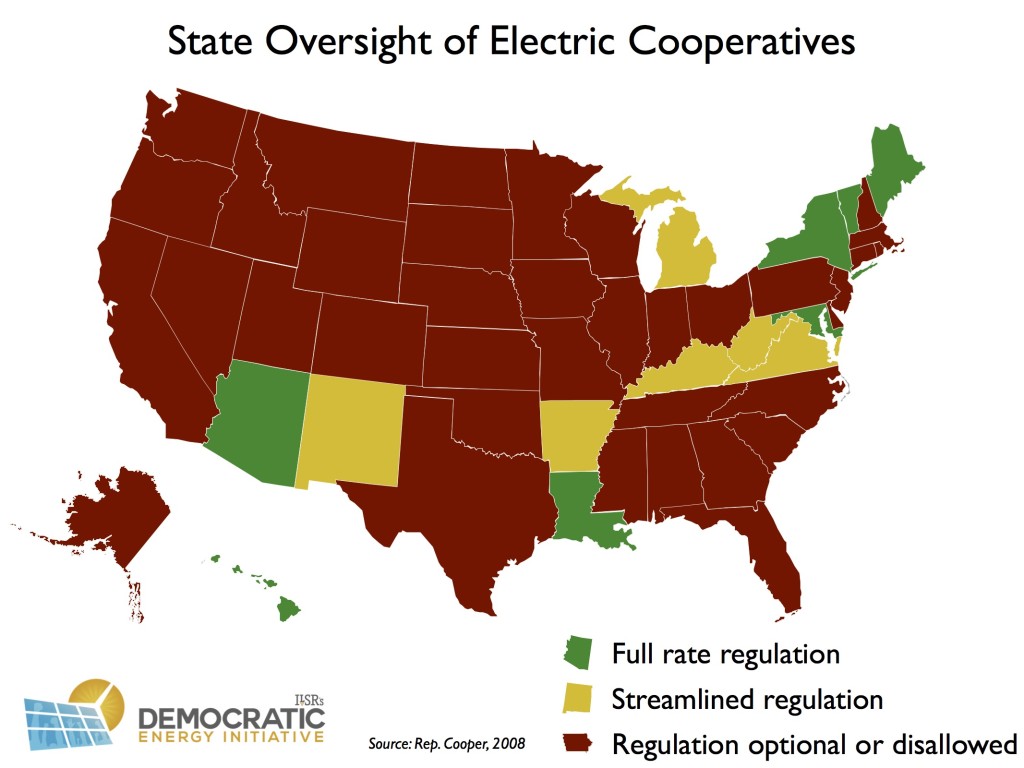

“Most electric co-ops are boys’ clubs that re-elect the same people, that develop policies that favor their children or their buddies,” says Tom “Smitty” Smith of the consumer rights advocacy nonprofit Public Citizen. Most states, Smitty adds, still believe in the myth of member-led rule and don’t regulate electric cooperatives at all (the following map illustrates state electric cooperative regulation as of 2008).

The electric cooperative has become increasingly obscure, and members, without realizing it, are losing control of the organization they own.

Democracy Reclaimed?

About a decade ago, says Smitty, the Pedernales Electric Cooperative was in trouble.

It started when a Pedernales member wanted information on how to upgrade his home with rooftop solar. Finding that the cooperative had no such program, he wanted to talk to the board, but he couldn’t get board member names. Everything, he soon found, was off limits to him, from board meetings to utility records. (FYI, it seems this anonymous member detailed everything in a pretty good documentary.)

Scandal ensued when a group of members and local newspapers dug deeper. It turned out that the Pedernales manager was stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars, and the board was deeply complicit and richly compensated.

Through bad press, pressure from legislators, and lawsuits, the board and management were forced out. Reform candidates were elected. A member bill of rights was passed, opening up the elections, nominations, and giving members full access to records and meetings for the first time.

The new board members formalized goals for 30 percent renewable energy in power capacity by 2020 and new energy efficiency savings. On the other hand, more conservative board members also passed through a fixed charge on the members and blocked rebate programs for renewable energy and energy efficiency.

Other cooperatives across the nation continue to expand voting and open records policies. Georgia Watch, a consumer protection advocacy group, even made a helpful study and checklist to determine if an electric cooperative is truly democratic.

Other cooperatives expanded voting and open records policies. At Kauai’s cooperative, in particular, the assurance for the democratic process has been extensive.

“We promote all candidates with campaign videos posted on our website,” board chairperson TenBruggencate says. “We publish an election guide. We have supported community candidate forums in some years. We have purchased advertising about the election. And we have made voting as easy as possible. We allow voting by phone, via internet, by mail and people can drop off ballots at our offices. The election is run and ballots are counted by an independent outside agency.”

Increased engagement at KIUC has helped soothe the strain of high electric bills, integrate record levels of rooftop solar, and bring innovative new projects in line with the members’ will, including a potential pumped hydro plant and the nation’s first utility-scale solar-plus-storage plant.

“Electric cooperatives need to stay in touch with their members,” TenBruggencate says. “Higher voter turnout gives directors indication of which platforms are resonating with those members. It can be used to provide strategic direction for the cooperative. An engaged membership will recognize threats to the cooperative, and help bring resources to bear to solve problems.”

Back in Kentucky at Jackson Energy Cooperative, Randy Wilson’s landslide loss wasn’t for naught. Proxy votes were outlawed shortly after the election. On-bill financing was instituted at the cooperative in 2010 as part of a pilot program with MACED. In 2013, an incumbent board member was defeated by a newcomer.

Change can happen at electric cooperatives. Wilson knows this. He remembers from the day of his election attempt, when he informed an election official that people were cutting in line to use their proxy votes.

“He said, ‘I guarantee this will not happen again,’” says Wilson. “I was warmed by his respect. I kind of hugged him… I didn’t feel any competitiveness.”

For more information, see ILSR’s other posts on rural electric cooperatives:

- Did FERC Just Smash the Biggest Roadblock to Clean, Local Power for Electric Co-ops?

- Why Aren’t Rural Electric Cooperatives Champions of Local Clean Power?

- A $6 Billion Opportunity for the Rural Energy Economy

This article originally posted at ilsr.org. For timely updates, follow John Farrell on Twitter or get the Democratic Energy weekly update.