In recent months, a raft of cities and states pushed up their renewable energy targets to 50%, 80%, or even 100%. But how will that energy be delivered? Will it be from the top down, by merchant wind and solar power plants? Or from the bottom up, by customers producing their own power?

The answer likely lies somewhere in between, but some studies of a low-carbon future rely too heavily on incumbent powers and utility-scale development for the energy of the future. A January 2016 study commissioned by the central U.S. grid operator — the Midwest Independent System Operator (MISO) — does yeoman’s work examining how to achieve a low-carbon energy mix across the region, but leaves many questions unanswered.

First, the Unfiltered Results

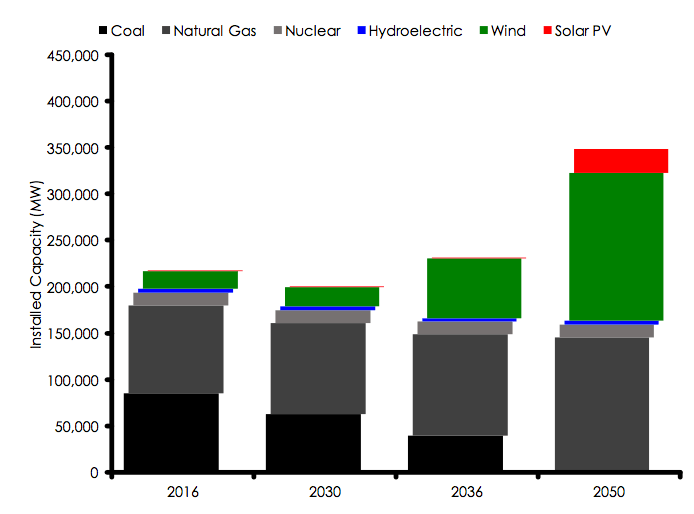

The MISO study suggests that achieving an 80% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 (from a 2005 baseline) is possible without increasing the cost of wholesale energy on the system. The 2050 Midwest grid would have zero coal plants, around 50 gigawatts of new gas power plants, and nearly 200 gigawatts of new wind and solar power. The following chart shows the projected installed capacity of each resource at a few benchmark years between now and 2050.

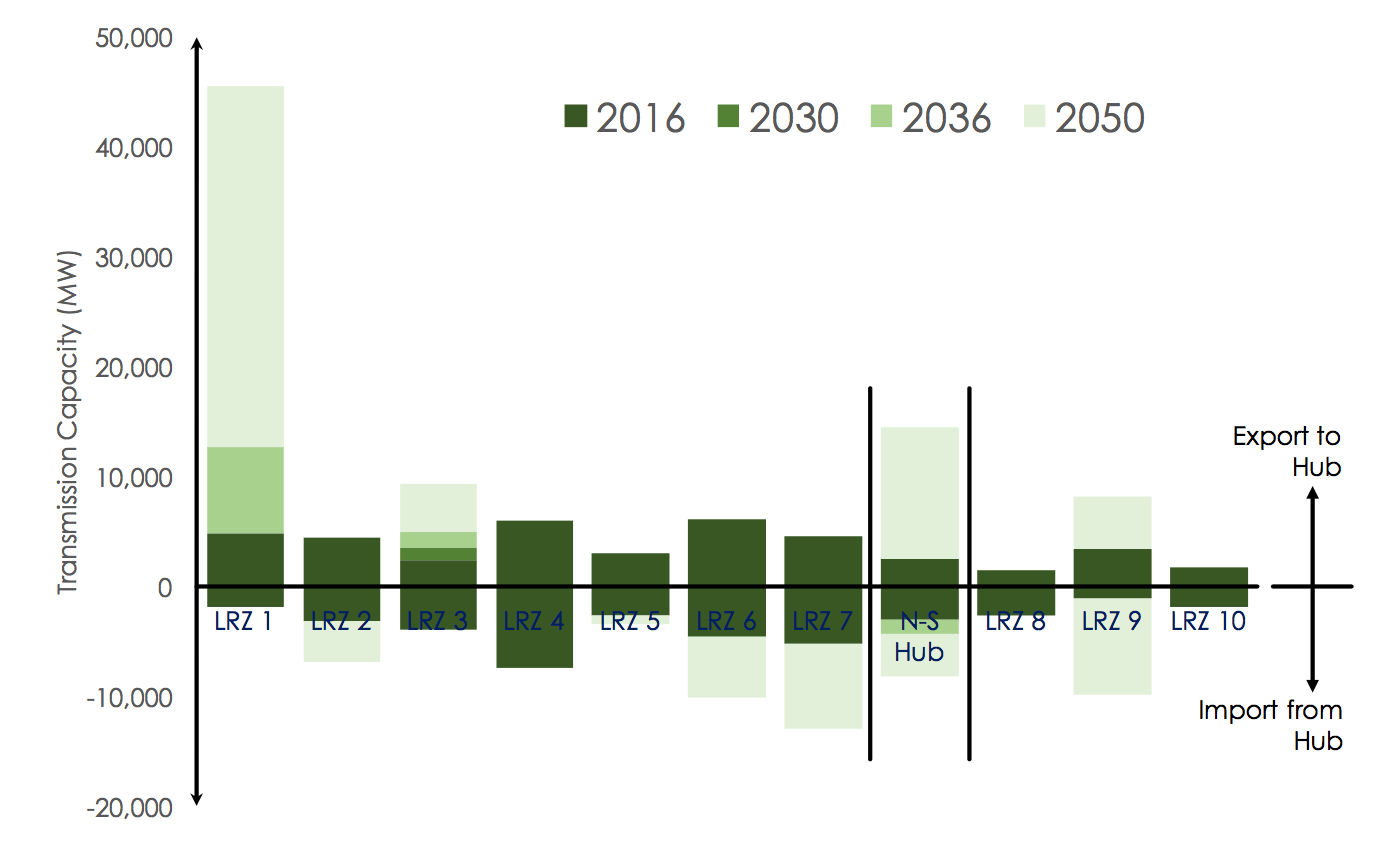

The low-carbon future examined in this study would require a massive transmission line expansion, with over 45 gigawatts of transmission capacity in MISO’s northernmost resource zone alone (primarily Montana, the Dakotas, and Minnesota). The chart below, from the study, illustrates.

Although it doesn’t dive into details, the study suggests this scenario carries the lowest cost region-wide, and that achieving similar carbon reductions in a constrained transmission scenario (presumably without the substantial expansion pictured above) would cost about 5% more per year.

Only 5%?

Ignoring for the moment the many factors aside from the transmission system that could alter this analysis in a way that reduces transmission needs — from distributed solar to storage to electric vehicles — let’s ask this question: would a state legislator or governor be willing to pay 5% more to increase in-state renewable energy generation rather than importing the electricity? Would a ratepayer?

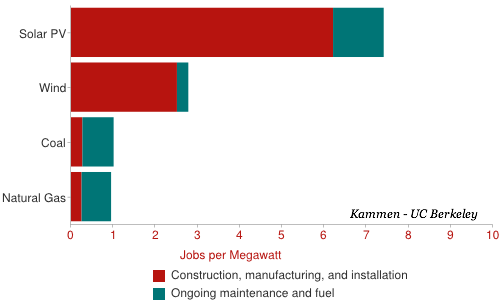

Typical economic impact estimates suggest wind projects create $1 million in economic activity per megawatt, while solar projects spur $2.5 million per megawatt. Both create numerous construction jobs.

Most studies of our grid system focus on the grid costs and benefits alone, leaving out economic benefits that tend to matter more to the affected communities.

The Many Things Ignored

Though the MISO study may offer an opening for more local renewable energy generation at a premium to transmission, it likely overstates the cost of achieving 80% carbon reduction by focusing too narrowly on the transmission system. It also includes other questionable assumptions. A few examples follow.

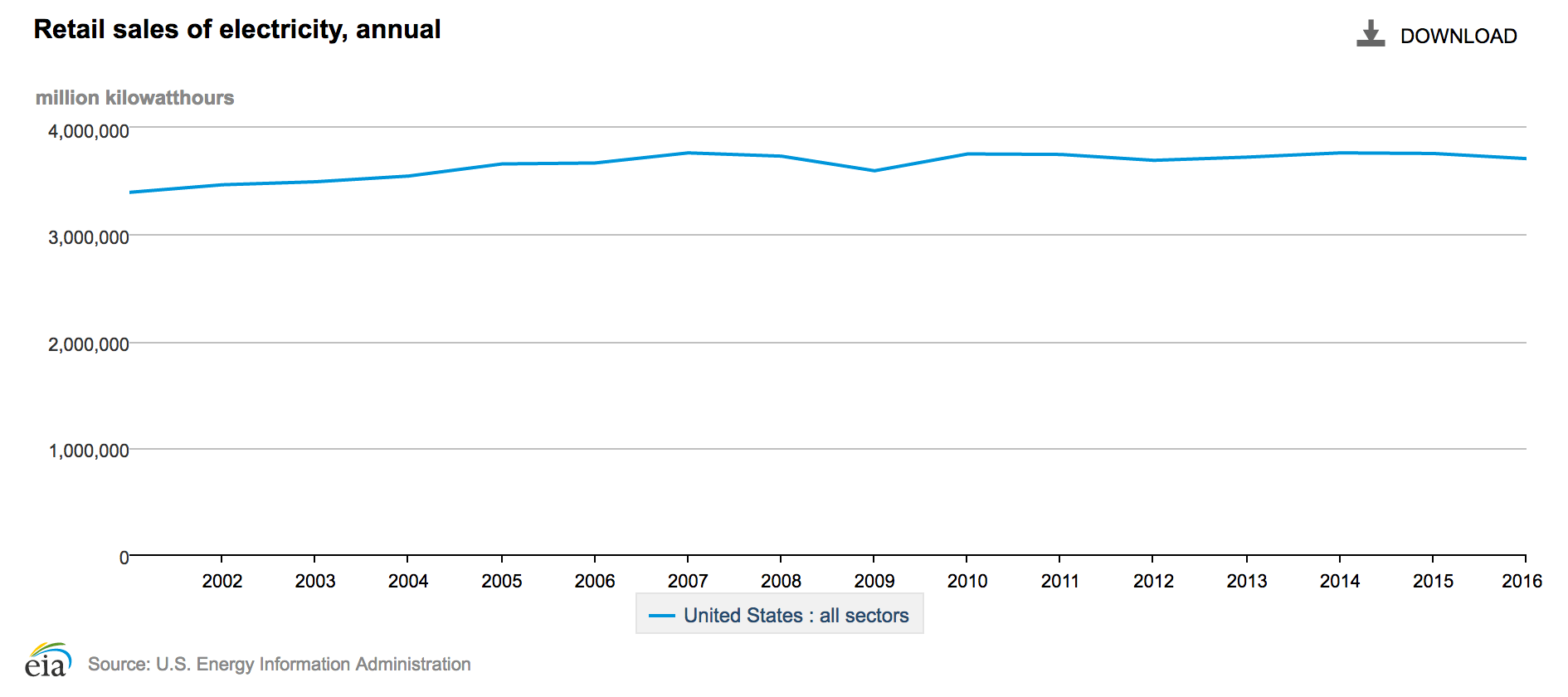

Stagnant Electricity Demand

The study assumes electricity consumption will rise by a constant 0.8% over the study period, despite stagnant electricity sales nationally over the past decade. If the trend of zero growth continues, this study overestimates total electricity sales (and therefore power generation needs) by 42%.

Electric Vehicle Adoption

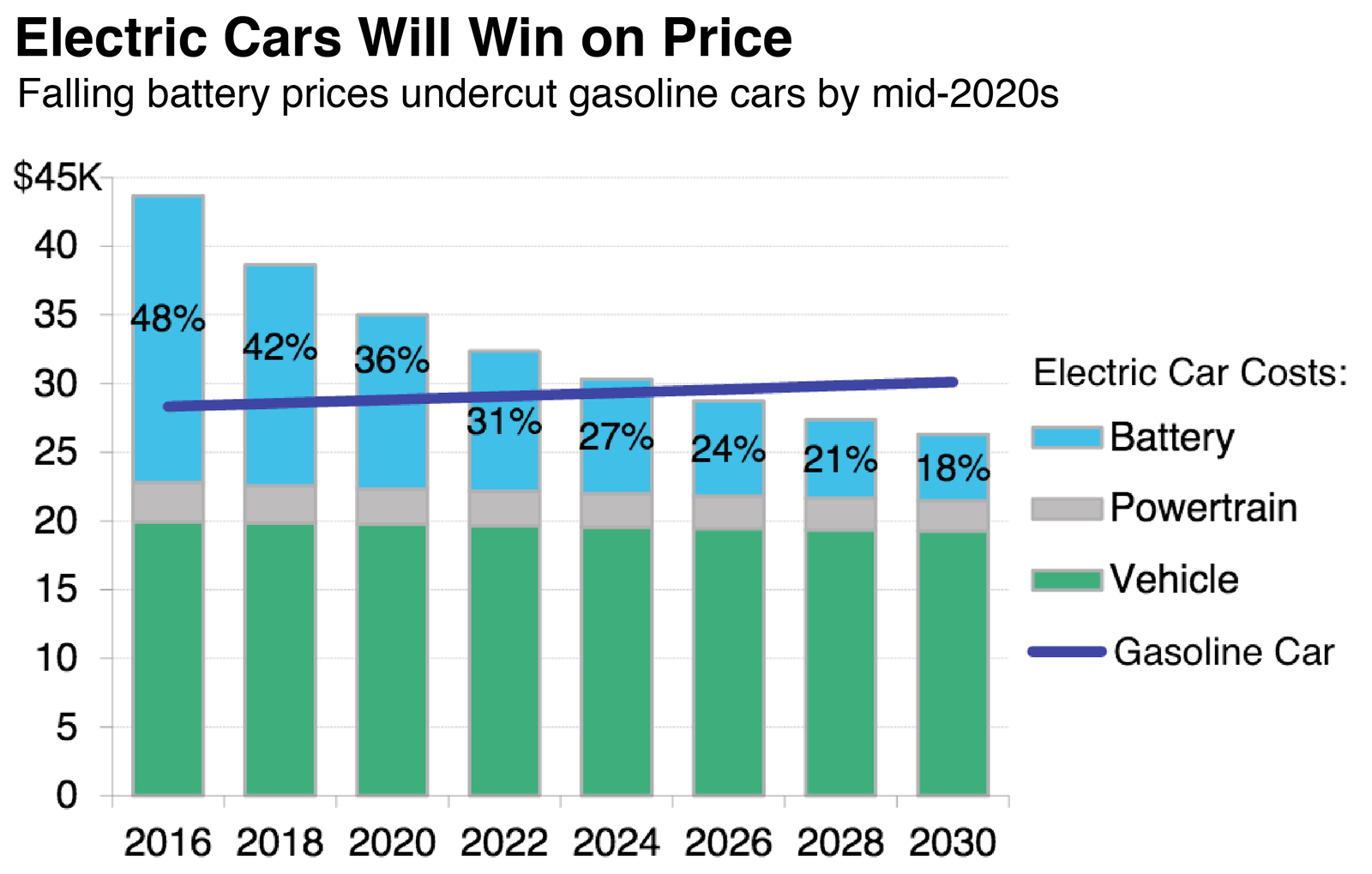

A countervailing issue is electric vehicle adoption, which by increasing electricity demand and sales may help correct for this odd projection of growth. On the other hand, electric vehicles offer a source of managed demand that can absorb excess electricity supply, in turn reducing the need for long-distance transmission. Bloomberg forecasts ongoing cost reductions that will translate to a substantial portion of the U.S. vehicle fleet going electric by 2050. Grid models run without acknowledging this assumption are dangerously suspect.

No Local Solar?

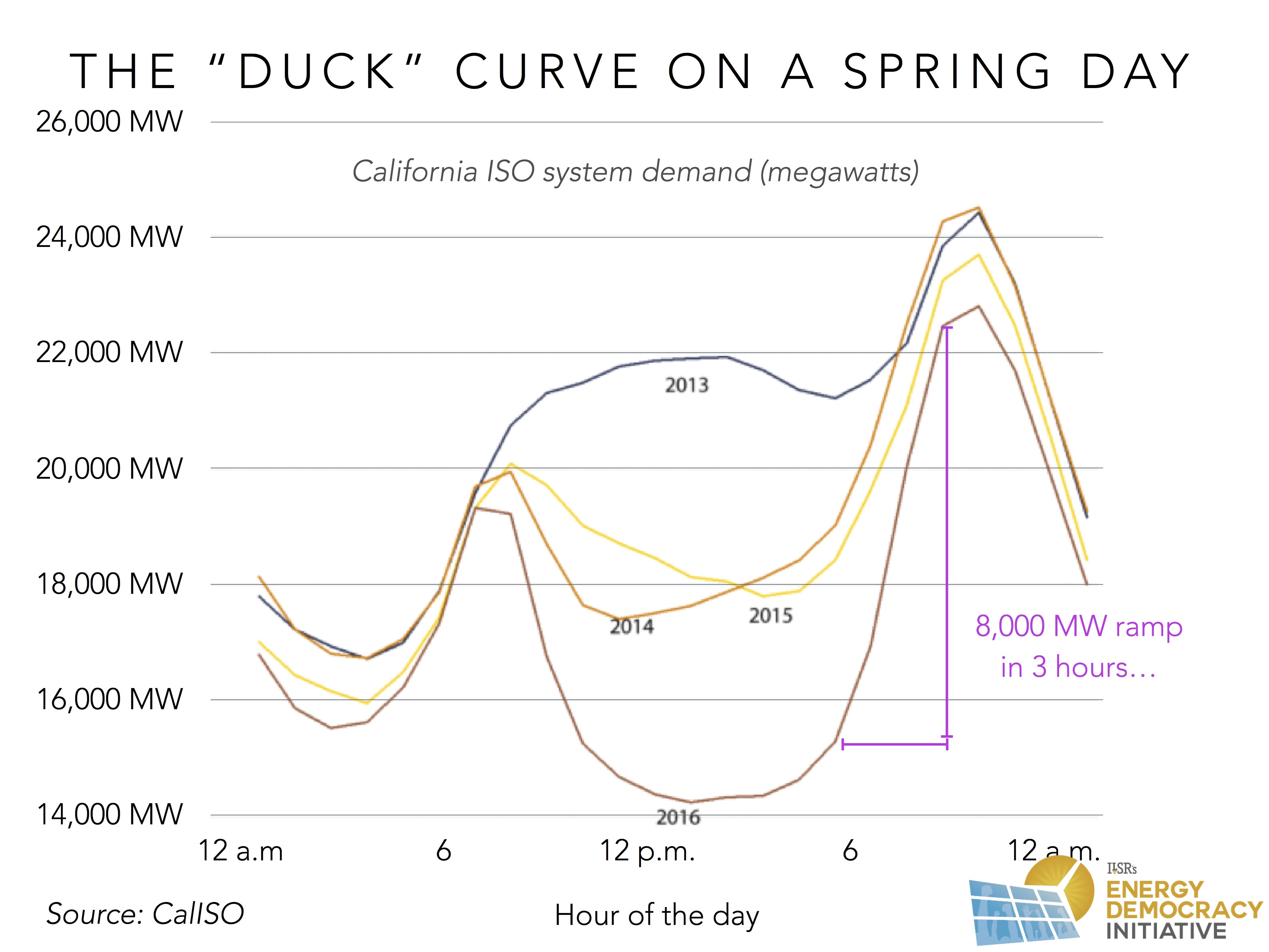

Distributed solar adoption is also ignored in the MISO study, presenting a major problem for modeling hourly system load matching. In California, for example, daytime solar production (largely from utility-scale solar, but also including distributed solar) is substantially changing the daily load curve.

No Energy Storage?

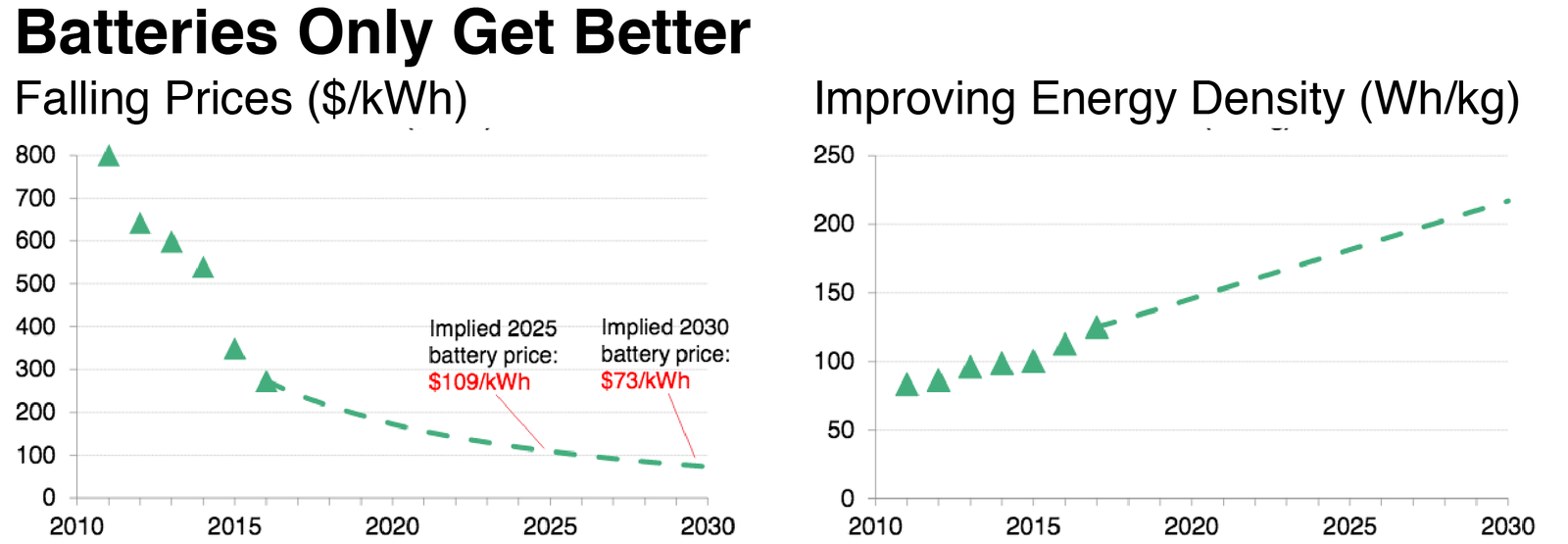

Finally, the MISO evaluation ignores the potential for energy storage. At 2016 prices, it’s no surprise that transmission offers a much more cost-effective tool for managing variable power supply and demand. But battery cost and energy density are improving rapidly, and to assume they will not have an impact in the 34-year study period makes the transmission-only analysis almost meaningless.

Narrow Studies Provide Poor Context

There’s a reason that in regulated utility markets, Public Utilities Commissions require utilities to conduct an alternatives analysis to determine the “least cost” method of meeting grid needs (unless the utility uses its lobbyists to avoid it). These assessments are intended to reduce the likelihood that electric customers overpay for electricity.

The MISO study provides an interesting slice of data, suggesting that it’s cost-effective to decarbonize the regional power grid. Its most useful lesson may be that managing demand within MISO’s zones is only incrementally more expensive than a massive transmission expansion, offering state policy makers viable options for focusing on local generation rather than long-distance imports.

Due to its omissions, however, the MISO study is totally insufficient for assessing the least cost method of decarbonizing the regional electricity system. Too many changes are bubbling up from the local distribution grid, and substantial technological innovation is likely to fundamentally alter the economics.

Photo Credit: Michael VH via Flickr (CC 2.0)

This article originally posted at ilsr.org. For timely updates, follow John Farrell or Karlee Weinmann on Twitter or get the Energy Democracy weekly update.