In 2011, the neighborhoods of Highland Park, Mich. went dark. The utility company had repossessed streetlights to collect on the city’s debt. Unwilling to stand idly by, the people of Highland Park organized to light the streets themselves using off-grid, renewable energy.

In this episode of Local Energy Rules, host John Farrell speaks with Maria Thomas, Outreach and Organizing Coordinator for Soulardarity. The two discussed energy democracy, and Soulardarity’s work in Highland Park, live in Milwaukee at the RE-AMP annual meeting. Highland Park, home to the first Ford Model-T assembly line, is suffering from economic downturn. As industry departed, the Detroit suburb shrank – along with its tax base. This left the city indebted to the monopoly utility company, DTE energy. To collect on this debt, without any notice, the utility pulled more than a thousand streetlights from residential areas.

Listen to the episode to hear how the community fought back against monopoly power, and see the episode notes and transcript below for more.

Podcast (localenergyrules): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

| Maria Thomas: | There is a slogan that DTE uses, that they want us to know our energy. We feel that we have the right to own our energy. |

| John Farrell: | What would your community do if the electric utility suddenly repossessed the city’s streetlights? Maria Thomas works with Soulardarity, a community nonprofit that’s been restoring light and power to residents of Highland Park, Mich. We talk about how Soulardarity has crowd financed new solar-powered streetlights, but more importantly how the advocacy group has given life to a movement for energy democracy in Highland Park. I’m John Farrell, director of the Energy Democracy Initiative at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance and this is Local Energy Rules. A podcast sharing powerful stories about local, renewable energy.

Maria, thanks so much for joining me. |

| Maria Thomas: | Well, thank you for having me, John. It’s a pleasure. |

| John Farrell: | Yeah, my pleasure to have you. Let’s start with the most visible project that Soulardarity has worked on, which is managing this city takeover or this, this installation of solar streetlights. What was the impetus behind Soulardarity and others in Highland Park working on solar streetlights? |

| Maria Thomas: | Well, as you mentioned, Highland park has an infrastructure that can support 70,000 people, including commuters. It’s the city of innovation. It is the city that Henry Ford chose to create the assembly line. So, the Model T was built in Highland park. However, due to decline, due to systematic racism, due to a number of factors, the population of Highland park now is estimated to be below 8,000. So you can easily figure out that the tax base was eroded. So consequently, some bills were not able to be paid. Highland Park had, um, accumulated a bill with DTE, our local, monopoly energy provider who provides gas and electric to our service area. So they had accumulated over 3 million, close to $4 million electric bill with DTE, for their administration costs. They were paying about $70,000 a month. So, because they couldn’t pay the bill, DTE in its benevolence decided to repossess two thirds of the street lights of the city.

So the industrial corridor and the commercial corridors were lit. However, the residential corridors were the areas that they chose to repossess. So, if you were walking to a friend’s house on a residential street from an industrial street, once you got into the block, say maybe 20 feet, it was as dark as it would have been during the blitz in London. If you entered the block further about 50 feet, you could hardly see your hand in front of your face unless you had some type of illumination. So at the time that this occurred, no one was notified. So it was a surprise to most residents of Highland Park. Jackson, my boss, who is the ED of Soulardarity, happened to be in Highland park for training. He had just been in, I believe it was Virginia, and had witnessed, the explosion, the blowing off of the tops of mountains to extract coal. So he became really rather engaged in environmental justice at that point, came to Highland park, realized what was going on, met with some people, as Jackson does. Very few people who are around Jackson leave without knowing who Jackson is and having at least the basis of a relationship with him. That’s the type of person he is. Brilliant beyond his years. But he met with, and started organizing with people from Highland park and concerned residents in the area and they began to crowd fund the solar lights. Number one, to advise, visually and physically the administration that this is an alternative. And secondly, to advise of the residents that there were alternatives as well. |

| John Farrell: | I have another question here about why community owned solar streetlights were the solution, for example, as opposed to trying to work something out with the utility. But I suspect even in just what you’ve already told us here, that the utility didn’t even notice the community it was going to remove the streetlights. And that it didn’t seem like it would be a very productive strategy to try to engage with the utility about fixing this problem. |

| Maria Thomas: | Unfortunately, in my opinion, DTE is not a very good neighbor, period. I live in Detroit. I love Highland park. I’ve always traveled to Highland park since I was a child, and I saw the decline of Highland park. I’ve seen the decline of Detroit. I’ve seen the quote-unquote renaissance of Detroit. It has not impacted very many long-term residents of the city of Detroit. I see now the gentrification that is moving into Highland park. However, to address your question, DTE not being a very good neighbor, does not see solar as being an alternative in certain situations. So even though we crowdfunded seven different streetlights at seven different times, all of these lights are still working, we’ve done a feasibility study, we’ve done surveys. We have submitted a proposal to the administration of Highland Park entitled “let there be light” that actually informed Highland Park with statistical data that the city would save a significant of money by installing the solar lights, owning the solar lights and not being subject to repossession because they would not be owned by DTE they will be owned by the administration. And as you may be aware, the wheels of bureaucracy – I say it all the time – spin ever so slowly. So after the proposal was submitted, there was some high level discussion, nothing of great significance. But the most significant action that I’ve seen with the administration is that in the fall of 2018, Jackson actually was graced with an opportunity to present to the administration the council of Highland park. And at that time several of the residents of Highland park, as well as Jackson, made presentations to the council and the council responded favorably. However, we have noticed that there are grid-tied streetlights being erected in Highland park as we speak without again, any notice to the residents. And the reason there has been no notice is because a loophole was used. DTE provided a voucher basically to the city of Highland Park’s mayor to get them to be encouraged to reinvest in streetlights that are grid-tied. And will be subject again to repossession. We have seen some of those streetlights erected. However, thankfully it is an election year in Highland park. So we are hopefully going to be able to educate residents of the city to work to seek favorable administrative replacements for those that are not favorable to, what I see is the next great thing to save the earth and also to help lift up the city of Highland Park and its residents. |

| John Farrell: | Well, it’s really clear that you have this, I think really stark lesson from the interaction with the utility that makes it awfully silly to go right back down that road of putting up grid-tied street lighting again. I’m curious to know if there’s some lessons from this. Highland Park’s issues with DTE came out of severe economic distress as you as you mentioned, but lots of other cities have utility owned street lighting. I’m curious, this is even a money saving opportunity for the city as well as an issue around ownership and control over the street lighting. I remember reading in preparation for this about some of the other potential uses for those streetlights. Once you have the infrastructure, for example, cities can rent out that infrastructure to mobile companies are trying to put up infrastructure for telecommunications. So they want to rent those poles. You could do citywide Wifi. So I guess one of my questions is would it make sense for other cities to stop paying their street lighting utility bill to kind of push this issue, knowing that there’s an opportunity here in some ways, both in terms of the economics of operating street lighting, but also in terms of the control and opportunities for deciding how that infrastructure is used. |

| Maria Thomas: | I would think that it would be a great opportunity for most municipalities to do so because, most municipalities, most governments are under stress. I don’t know about other areas of the country, but part of the depression of economic concern in Detroit and Highland park is the fact that the state used to share the wealth with the city and it would support some of the issues that needed to be supported in the city. Well, they no longer do. And when that money was removed, there was nothing to replace it. So, whatever a city can do to cut their costs, to reduce their costs, also to reduce their carbon footprint, it is not only good economically, it’s also good for the residents as far as health is concerned. Because you don’t have to worry about the transmission lines and you don’t have to worry about so much of the fallout from the infrastructure that DTE uses to tie to the grid.

If the utilities don’t want to be good neighbors, if they don’t want to be concerned about people, if they want to think of people as beings to be counted by an accountant, then we need to walk away because the business model is very archaic. It is not sustainable. And as well as the earth, we need to be able to sustain the earth and we can’t do it if they will not join us in that battle. And there is a slogan that DTE uses that they want us to know our energy. We feel that we have the right to own our energy. We should all be able to take advantage of it, no matter what our economic status, ethnicity, religion, whatever, we’re all human beings. It will remove a lot of the stressors of poverty. It will create new living wage jobs. It will decrease the carbon footprint. We need to reduce all of that so that we can all live peacefully and seek to obtain, as was mentioned earlier today, the American dream: own a home, send a child to a good school without having to fear the child being attacked or go to work if you have to take the bus and have a lit street, be assured that there’s no energy insecurity in your home because you’ve been able to reduce or remove your obligation to the utility and your being able to garner a great gift that was given to us – whether you believe in the Creator or not, it’s a great gift. The Sun is an obviously fantastic and a blessing to us and we need to take advantage of, I believe it was put there for us to take advantage of it. |

| John Farrell: | So you’ve kind of highlighted this already. If you could just briefly talk about Soulidarity’s role in the streetlight project specifically? So it sounded like you, the organization helped to do the community financing of the streetlights that had been put back in. Talk a little bit more about some of the greater mission. There’s also this thread about owning energy. What would the outcome be? What would the community look like if Soulardarity could be successful in restructuring the energy system in the way that you envision? |

| Maria Thomas: | I believe it would be a very prosperous community if all of these factors align. There is, as I mentioned before, a committee that is working fearlessly to seek that outcome. They are endeavoring to be 100% clean using all types of alternative energy with a focus on solar, but also using water, also using geothermal. Not too much with wind, because we do have quite a bit of land, but we see the land as a possibility to provide us with community solar because there are a significant number of renters in the city with an average income in the city of less than $20,000 per year. And, as you may know, the poverty level is estimated at $24,500 for a family of four. So imagine a single mother who’s working two jobs, as Donny says, unemployment among Blacks and African Americans is the lowest it’s ever been. Well, if you’re working three jobs with no benefits to keep a roof over your head, that is not a positive advancement and fun with numbers has been played with unemployment for decades.

So we see and envision businesses coming back to Highland park. We see a Henry Ford’s original factory being rehabilitated and used for small businesses and larger businesses. We see the public school system coming back, and us being able to assist in educating those children about the advances and the opportunities that are bound in sustainable energy. We’ve had the opportunity to do it already. And with Soulardarity and outside of Soulardarity, I’ve introduced young people to sustainable and alternative energy and they have soaked it up like sponges. Occasions where I thought I would get maybe 200 students to come by and see a veggie truck, where they were using recycled vegetable oil to run an F350, but instead I got almost the entire population of a high school. 1200 children plus their parents. So I envision that we will be prosperous and that there will be peace and that the city will begin to repopulate so that it can actually support that infrastructure. |

| John Farrell: | We’re going to take a quick break. When we come back, we’ll take a short tangent to talk about Hawaiian shirts, before asking Maria about the challenges facing Soulardarity’s Highland Park work, how they pursue a more equitable energy system, and how other communities can get on board the energy democracy bandwagon. |

| John Farrell: | Hey, thanks for listening to Local Energy Rules. If you’ve made it this far, you’re obviously a fan and we could use your help for just two minutes. As you’ve probably noticed, we don’t have any corporate sponsors or ads for any of our podcasts. The reason is that our mission at ILSR is to reinvigorate democracy by decentralizing economic power. Instead, we rely on you, our listeners. Your donations not only underwrite this podcast, but also help us produce all of the research and resources that we make available on our website and all of the technical assistance we provide to Grassroots organizations. Every year ILSR’s small staff helps hundreds of communities challenge monopoly power directly, and rebuild their local economies. So please take a minute and go to ILSR.org and click on the donate button, and if making a donation isn’t something you can do, please consider helping us in other ways. You could help other folks find this podcast by telling them about it, or by giving it a review on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. The more ratings from listeners like you, the more folks can find this podcast and ILSR’s other podcasts — Community Broadband Bits and Building Local Power. Thanks again for listening, now, back to the program. |

| John Farrell: | I just have to ask, because it was in his bio, but what is with Soulardarity’s executive director and Hawaiian shirts? |

| Maria Thomas: | I am the wrong person to ask that question. Jackson does have a significant and diverse Hawaiian shirt collection. We had a coworker last year and they had contests as to whose Hawaiian shirt was most vibrant and was the best shirt of the day. Jackson enjoys the comforts and the vibrancy, I believe, of a wonderful Hawaiian shirt. And if it is above 30 degrees, you’re subject to see him in one. |

| John Farrell: | Well, I noticed that he had one on today, for example. I’m sorry he wasn’t able to join us, but that’s a good question. A follow-up question for him then. |

| John Farrell: | One of the things I would love to give people a sense of in this conversation is about both the successes and the challenges. Clearly the solar streetlight itself is a high point in the ability to raise some money and to install those streetlights as well as making some inroads with the city and considering investing in more of them. What do you think has been one significant challenge for Soulardarity’s work? |

| Maria Thomas: | Money. Resources, time, capacity. We need more people on the ground to do the work. I’m a person of faith, so as the Word says, the harvest is great, but the workers are few. So consequently, we have a lot of work to do. There are not enough people in the movement. There are not enough people of color in the movement. There are not enough people who have been impacted by the oppression and the oppressive nature of energy providers or other polluters, that are directly suffering because of various components of the corporate conglomerate – that seeks to extract as much money and resources from the earth as they possibly can no matter what the outcome is with people. So those are the challenges that we face. We have climate deniers, we have corrupt politicians that we deal with. We have a Republican and regressive legislature in the state of Michigan.

We just elected a democratic governor and the attorney general, so they are making some very progressive moves to bring us into the 21st century. But we are not aware of, all the time, where the resources will come from. And we also are fighting diligently for energy democracy amongst our community so that we can own the power and we can lift the community and we need more engagement from the community. But it’s specifically to educate people and allow them to create a vision of what they want to see. So as an energy democracy, we want our members, because we are a member driven organization, we want our members to tell us, do you want this number one and how do you envision it number two. But that’s not as much of a challenge as just getting folks to come to the table. So I would say getting people to come to the table and resources. So money and in kind contributions are gladly and happily welcome to Soulardarity. |

| John Farrell: | It’s interesting in terms of the solar streetlights have really, I think caught the attention of a lot of other folks. There’s quite a few stories already that have been written about that work. And I think that is a powerful example of how doing something concrete is really helpful in inspiring people and in and in giving people something to act around. What advice do you have for folks in other communities who might be starting down this path? Maybe they’re also working on this 100% renewable energy idea. Maybe they’re simply focused on this notion of energy ownership and energy democracy. Where should they start? What, what important lessons could they learn from the work you’ve been doing in Highland park? |

| Maria Thomas: | That it’s not easy. That it’s not going to happen overnight. It may be easier if you have money to do so. Say an angel funder drops out of the sky and just gives you a couple of million dollars to fund the groundwork to fund the foundation of creating such a movement. There is a lot of interest in solar street lighting in particular. We’ve had a suburbs of Detroit that have requested that we do an assessment of the areas that they would like to invest in. And the ones that we’ve been working with are also closely working with the governments of their city. So consequently, assessments that we did in the spring of 2018 have yet to make it to the table so that we’re notified of the fact that we could bid on what we assessed in 2018 in the spring. If you intend to do it privately, you need to be educated on how you can proceed, because you don’t have to have a permit generally to put the light up on private property. But you do have to have permission if it’s in the easement between the sidewalk and the street. If you have those in your area. You need people, so that you can educate your community. And the more people that you educate and the larger your organization or your movement becomes, the easier it is to attract money. Especially if you have a good grant writer. And there’s always opportunities such as the fact that we are here at the REAMP annual meeting discussing equity. So we need equity in a lot of communities that are oppressed and don’t have those resources.

So anyone that has those resources that is listening, please contribute to those movements that are seeking to level the playing field and become involved in an equitable, fair, and just transition away from fossil fuels. If you want to donate to Soulardarity, I’ll tell you right now, the check should be made out to Soulardarity, s o u l a r d a r i t y . 21 Highland Street in Highland Park, Michigan. Zip code is 48203. |

| John Farrell: | Well done, I think my development director is probably gonna listen to this podcast and ask me why I haven’t been including that kind of donation request at the end of each one. I wanted to wrap up by noting that Soulardarity is hosting an energy democracy convening in July. I don’t have a lot of time to go into a lot of detail, but I think it would be great to tell people who follow this podcast and who are very interested in the concept of energy democracy, what’s the goal for that? Why is this convening happening? Why should people come? |

| Maria Thomas: | The urgency of now, it was discussed here during the REAMP annual meeting. The urgency of now is, everyone that I speak with that’s in our circle agrees that it seems like there’s a bubble or a window of time that people are more aware, more woke. We have an inter-generational span of people from teenagers to seniors who are becoming more and more interested, more engaged, and more passionate about saving the earth, meeting certain standards by in the next 10 years. Because of the fact that science is stating that if we don’t change the trajectory of the heat of the earth and the carbon footprint within the next 10 years, we’re going to actually kill ourselves. So we will damage the planet. The planet may survive, but people and the millions and millions of creatures that live on this earth probably won’t if we don’t change.

And we need to understand, no matter what your socio-economic status or racial status, religious background or not, whatever your status is, the time is now to make a change and do the right thing because it’s the right thing to do. And we need to get over ourselves. As far as all these little differences that we have. I believe that 90% of what people are concerned about is the same thing that someone across the country is concerned about and the 10% that’s a difference we need to celebrate and get to know people better, and as was stated, to love each other. We’re all human beings, we’re all in the same boat. The boat has numerous holes in it, so we need to get to work to save the boat as an analogy. So that’s some of the work that we’re doing with the energy convening. |

| John Farrell: | Well, Maria, thank you so much for talking with me and sharing the story of Soulardarity’s work. I hope some people take you up on that opportunity of writing you a check. |

| Maria Thomas: | 21 Highland street, Highland park, Michigan, four eight two oh three. And if you have any questions, call me. (313) 422-3242. It’s been my pleasure. John. Thank you so much for the opportunity and I hope that this meets your goal and that you all can continue to successfully produce these. I believe it’s an important aspect of spreading the word and bringing people that have interest into the circle. Thank you so much. |

| John Farrell: | There’s certainly been no shortage of stories to tell, so we’ll keep at it. And as always, there’ll be more information about Soulardarity’s work on solar streetlights, their work on energy democracy, and this convening on our show page. So thanks again Maria. |

| Maria Thomas: | Thank you so much. Have a great day. |

| John Farrell: | This is John Farrell, director of ILSR’s energy democracy initiative. I was speaking with Maria Thomas of Soulardarity in Highland Park, Mich, about their efforts to restore local power. Learn more about policies and actions communities can support energy democracy by digging into ILSR’s interactive Community Power Map and Community Power Toolkit — both available at ilsr.org — that is I – L – S – R – dot – org. While you’re at our website, you can also find more than 80 past episodes of the Local Energy Rules podcast. Until next time, keep your energy local and thanks for listening. |

Building a Coalition

After DTE took the streetlights, Maria Thomas describes the difficulty of seeing one’s own hands in the darkness. The repossession, which Thomas jokingly calls “benevolent,” left Highland Parkers more vulnerable when outside at night or walking to the bus stop at dawn.

To respond, a local initiative grew with an idea to replace the streetlights. Thomas notes that in order to prevent a second repossession of the lamps, they had to be independent of DTE’s grid. One way to do this was by installing street lights that generate their own electricity through solar.

Through community crowdfunding, Highland Park was able to install its first off-grid, solar streetlight in 2012 – near the old Ford factory. To capture this momentum and install even more streetlights, the group Soulardarity was formed. Thanks to both local fundraising and a partnership with the 100% Project, Soulardarity has installed a total of seven solar lights in Highland Park.

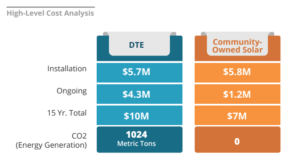

Realizing the cost-saving potential of buying the lights in bulk, Soulardarity began to think bigger. In a proposal to the Highland Park council, entitled “Let There Be Light,” Soulardarity outlined the benefits of ditching DTE and drawing the city out of the dark with solar. By replacing all of the grid-tied streetlights with their solar superiors, Soulardarity found that the city could save three million dollars over 15 years.

Data from Soulardarity

If the cost-savings weren’t enough, community-owned streetlights bring many other benefits. Thomas emphasizes their role in reducing carbon emissions and creating jobs, both of which facilitate greater peace and stability in the community. Having local control over streetlights in Highland Park would build up energy democracy, an energy system where everyone has a say. As Thomas says in the interview:

There is a slogan that DTE uses, that they want us to know our energy. We feel that we have the right to own our energy.

Energy democracy is key to the mission of Soulidarity: they want stakeholders to have a place at the table. Thomas says that “we should all be able to take advantage of [renewable energy], no matter what our economic status, ethnicity, religion, whatever, we’re all human beings.” Energy democracy is part of energy justice, an important framework in Highland Park. As a predominantly black and African-American city, redevelopment without democracy could mean gentrification and the displacement of a community with deep ties to the area.

Soulidarity wants to engage those most affected by energy decisions, Thomas explains. “There are not enough people of color in the movement.” There needs to be more people “who have been impacted by the oppression and the oppressive nature of energy providers or other polluters, that are directly suffering because of various components of the corporate conglomerate.”

Soulidarity does this work through outreach and education. Thomas describes her work teaching children about sustainable energy, which she hopes will soon be a part of the public school system. She also engages in outreach to adults to grow the movement, but sees this as another challenge.

As an energy democracy… we want our members to tell us ‘do you want this?’ number one, and ‘how do you envision it?’ number two. But that’s not as big a challenge as just getting folks to come to the table.

Click here if you would like to support Soulardarity’s work through a donation.

Utilities as Bad Neighbors

Thomas describes how DTE Energy found a loophole to install grid-tied streetlights again. By giving the mayor a voucher, the utility is encouraging the city to reinvest in the expensive infrastructure that was just taken away. Now, DTE has begun to put utility-owned streetlights back in, without notifying Highland Park residents. Thomas decries this activity as yet another crooked tactic.

If the utilities don’t want to be good neighbors, if they don’t want to be concerned about people, if they want to think of people as beings to be counted by an accountant, then we need to walk away because the business model is very archaic.

For more on the shady practices of monopoly utilities, listen to this Building Local Power podcast entitled “Energy Monopolies: The Dark Side of the Electricity Business”

Not Confined to Highland Park

There’s no need for financial troubles to push the switch to solar lighting. In fact, many cities and communities are beginning to evaluate the benefits of solar. The city of Beaumont, Calif. passed an ordinance in 2015 that all new street and park lights must be solar. More recently, a company is testing out four streetlights in Las Vegas that are powered both by solar and by kinetic energy captured from pedestrians.

Where communities already own their public lighting, many are turning to LED bulbs. Los Angeles has replaced its conventional streetlights with LED versions, which significantly reduce energy use and can charge electric vehicles.

Switching to smarter technology is not just happening in eco-friendly California. The cost-effective switch to LED streetlights has been happening quietly all over the country, in cities large and small. According to a report led by The Climate Group, “converting all US street lighting to energy efficient LED lamps would save US$2.3 billion and prevent approximately 15 million tons of CO2 from entering the atmosphere. This is equivalent to taking more than 3 million cars off the street.”

Always Looking Forward

Although Thomas seemed disappointed in the re-installation of grid-tied streetlights, she looks ahead to alternate plans of action. She mentions that it is election year in Highland Park; she hopes to organize support around candidates who will act in the people’s interest.

Another project of Soulardarity is the “PowerUp Program,” which has facilitated the installation of over 100 solar lights by arranging group purchasing.

Soulardarity is also planning outreach on many types of renewables, not just solar. Thomas voices a desire for 100% clean energy and describes her ideal version of a thriving Highland Park. To get there, they need resources, community engagement, and plenty of hard work.

I’m a person of faith, so as the word says, the harvest is great, but the workers are few. So consequently, we have a lot of work to do.

Thomas also looks forward to an Energy Democracy convening Soulidarity is hosting at the end of July. Through the conference, the group hopes to harness “the urgency of now,” find common ground, and take actual steps toward a more democratic energy system.

Episode Notes

For more on the Soulardarity story, check out this video produced by the organization. Also, listen to this podcast by Cool Solutions featuring Jackson Koeppel, Executive Director of Soulardarity.

For concrete examples of how cities can take action toward gaining more control over their clean energy future, explore ILSR’s Community Power Toolkit.

Explore local and state policies and programs that help advance clean energy goals across the country, using ILSR’s interactive Community Power Map.

This is the 81st episode of Local Energy Rules, an ILSR podcast with Energy Democracy Director John Farrell, which shares powerful stories of successful local renewable energy and exposes the policy and practical barriers to its expansion.

This article originally posted at ilsr.org. For timely updates, follow John Farrell on Twitter, our energy work on Facebook, or sign up to get the Energy Democracy weekly update. Energy Democracy Director John Farrell assisted with editing the summary post for this episode.

Featured Photo Credit: Marcelo Braga via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Photo Credit: Thomas Hawk via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)