How does a growing, national nonprofit organization help homeowners complete the circle between clean energy ownership and policy advocacy? ILSR’s Energy Democracy Initiative director John Farrell talks with Anya Schoolman of Solar United Neighbors in this October 2018 recording about two major clean energy policies before the Washington, D.C., city council. Support for the policies comes from the advocacy efforts of many residents enabled by Solar United Neighbors to become solar owners by banding together, a model that has spread to over 10 states.

Podcast (localenergyrules): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

John and Anya last talked in 2015, when local residents were opposing a bid by the nation’s largest utility to takeover the incumbent investor-owned utility in D.C., Pepco. The D.C. Public Service Commission had rejected the merger, but the city and utility were back with a settlement agreement that had plenty for utility shareholders, and little for customers. The first ever Local Energy Rules podcast also features a conversation between Anya and John about the precursor to Solar United Neighbors.

| John Farrell: | How does a growing national nonprofit organization help homeowners complete the circle between clean energy ownership and policy advocacy? Anya Schoolman is the executive director of Solar United Neighbors, a national nonprofit organizing solar buying cooperatives in nine, soon to be 12 states. I spoke with her in October 2018 about two powerful new local energy policies under consideration in Washington D.C. and of the role of Solar United Neighbors in connecting solar owners to solar policy. I’m John Farrell, director of the Energy Democracy Initiative at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance and this is Local Energy Rules, a podcast sharing powerful stories about local renewable energy.

Last time we talked, it was a different issue. It was about monopolies and about the proposed merger between Exelon and Pepco in Washington D.C. We’re back because there’s some new and interesting policy things happening in Washington D.C., some great news in terms of growth for Solar United Neighbors. Anya, welcome back to the program. |

| Anya Schoolman: | Thanks for having me, John. |

| John Farrell: | So, I just have to start with a disclosure. I’m a volunteer board member of Solar United Neighbors. So, I’m working with Anya in a lot of different respects. But I would like to say that it’s out of mutual admiration or each other’s work, certainly on my part, for what Solar United Neighbors is doing. We’ll get into that a little bit. A key focus of Solar United Neighbors, of course, is connecting solar customers to ways to support solar policy. So, I did want to ask you about these two really interesting bills in front of the D.C. city council, which is your legislature.

The first one I was interested to ask you about, it’s called the Clean Energy D.C. Omnibus Amendment Act of 2018. It’s a mouthful. But there are a lot of different pieces in there. But one of them is 100% renewable energy standard by 2032, which is very aggressive. There are some other really interesting things, including some targeted energy assistance for low income customers. So, I’m just interested in getting your perspective. Is this bill a good thing? Are you excited about it? Are members working it? Tell me more about what’s going on here. |

| Anya Schoolman: | The bill’s a great thing. We’re excited about it and really, the broader community in D.C.’s really excited about it. But it’s really fascinating to see what happens when you try to go to 100% because it opens up a different set of can of worms. In some ways, it sounds incredibly aggressive, like 100% by, whatever it is, 2030, 2035. |

| John Farrell: | 2032. |

| Anya Schoolman: | 2032. In some ways, that’s not very aggressive at all because D.C. is a very small island within the larger PJM. We could actually decide to go 100% tomorrow because there’s enough renewables in the grid and enough recs around and you could just do it. It wouldn’t even be that expensive because our small size compared to the larger regional grid. So, the devil’s in the details. So, there’s been incredible arguments about the definition of what’s 100%. Is that new renewables? Is that existing renewable energy credits? Is that within the grid? Is that a local thing? Can you buy recs from Texas and will that count?

So, it’s really the first time where the debate within the community is about the implementation details rather than the goal. There’s big repercussions for that. So, that’s been really hard. Then there’s this really weird thing that happens. Tell me if I’m talking too long. But when you go to 100%, all of a sudden, these questions come up like, well, if we’re 100%, do we still need to do energy efficiency? Because it’s all renewable in theory, right? |

| John Farrell: | Right. |

| Anya Schoolman: | Do we still need this local solar? So, there’s been this whole other cascading series of arguments about what does that mean to the local programs? Because D.C.’s been leaning in really hard on local efficiency, low income solar, locally, rooftop solar for a long time. Does that suddenly mean we don’t need to do that anymore? Of course, the local community says absolutely, we have to do it all. But it’s really opened up a weird philosophical debate. |

| John Farrell: | So, I’m curious. Correct me if I’m wrong, and obviously, I have a perspective, being from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, about this notion. But it seems that energy efficiency or local solar really serves a different purpose to some degree. Obviously, those things can contribute to meeting 100% renewable goal by reducing the amount of energy you have to buy and also by producing some of it near at hand. But you’re also giving people a chance to have an investment in the energy economy to reduce their energy bills. Isn’t there a lot of upside to that? |

| Anya Schoolman: | There’s a huge upside. There’s been thousands and thousands of jobs created in D.C. with the local solar program and the local energy efficiency. There’s also a huge equity impact because the big thrust of D.C. spending on both solar and energy efficiency is for low income households. We have this incredible program called Solar For All, which we passed a year ago now. No, two years ago now. 2017. That law requires D.C. to build local rooftop or parking lot solar to offset the bills of every single low income household in Washington D.C. by 50% by 2032 or ’35. It’s the same date.

So, the question is does this new bill endanger the existing program? Because if you don’t continue to have a strong solar carve out, which is what financed the program, do you lose funding for the program? I think it’ll all come together in the end. But you caught us right in the middle of the scrum of the details of exactly how this is going to work out. |

| John Farrell: | Well, I’m really glad you brought that up, though, because number one, there is such a strong movement around the country right now. I’m hearing this in almost every state that’s talking about community solar or solar energy programs is how do we let everybody participate? So, I think it’s great that D.C. has already put a stake in the ground around that. But it really does raise this big question because we’re going to see, and we’re seeing in the Midwest, some utilities going, “Oh, we’re going to 50 or 60 or 80% renewable,” one in Iowa saying, “We’re going to go 100% renewable.”

So, to what degree are those economic benefits going to be shared? Because is the utility does it, they’re going to pay a few big project developers to build wind farms and solar farms. We’ll get clean energy, and maybe we have to pay a little extra for the transmission lines to get it to where we are going to use it. But what we’re talking about here really is the tension then between can we get to this larger goal, but also can we do it in a way that respects the opportunities, the jobs creation, etc., that comes from distributed energy? |

| Anya Schoolman: | That’s exactly right and we’re literally having that debate once again. We built a consensus for rooftop solar. We built this huge constituency for it. There’s all these local D.C.-based companies employing D.C. people. I don’t remember the number, but it’s thousands and thousands of people employed. Then there’s this other side, which has come in, especially people that haven’t been involved in this last 10 years of building this local market and they’re like, “Well, it’s more efficient if we just buy it out somewhere else. If we want to get to 100% faster and cheaper, why muck it up with all this local stuff?”

So, we’re revisiting that debate. But I think in the end, D.C.’s going to do what’s best for the people who live in D.C. We have the luxury of being a city-state. So, it gives us a little bit more democratic control over what happens. There’s not a bifurcated sort of rural-urban kind of issue or anything. It’s just the city. |

| John Farrell: | You don’t have different metro stops warring against one another. |

| Anya Schoolman: | We don’t. It’s not regional. D.C. has eight wards and all eight wards want local rooftop solar. That’s a unanimous viewpoint. |

| John Farrell: | So, I wanted to say for people who want to dive deeper around this notion of the scale of energy and efficiency, ILSR does have a report called Is Bigger Best where we dive into some of that economic argument. But I wanted to also ask you then about, because it’s actually related to this notion of scale, the second big bill that’s in front of the D.C. council, looking over here at my notes, it’s called the Distributed Energy Resources Authority. This is really fascinating because it’s not just going a big step further in terms of how far we’re going to get in terms of renewables in the way that 100% is setting this big, audacious goal. It’s really about market structure.

This thing is saying, if I read it right, instead of the utility company deciding how we might deploy infrastructure to support the grid, we’re going to have this independent authority demonopolizing that decision making and letting people bid in with other solutions that might include rooftop solar and storage. So, first of all, do I have that right? Tell me a little bit more about why that’s exciting. |

| Anya Schoolman: | I think you basically have it right. It is a radical bill and it’s meant to be. Depending on who you talk to, some people are seeing it as a shot across the bow of the utility, Exelon, and the public service commission. We have a grid reform or a grid modernization proceeding going on. It’s moving less than the pace of molasses. So, part of it is democratic counter push to that. But the people who introduced this bill and who’ve been working on it are serious about it. It’s not just for show.

We do have a case in D.C. right now. It’s a big infrastructure case, it’s the Mount Vernon Square, where the utility’s proposing to build a big substation and it’s actually going to go on top of a neighborhood community garden. The D.C. Department of the Environment has paid for an analysis showing that a non-wires alternative would be cheaper for rate payers and a more effective and more resilient solution. So, we are actually in a docket fighting that particular case right now. Then along comes this DERA bill and the DERA bill requires a non-wires alternative analysis for every infrastructure upgrade. |

| John Farrell: | It’s funny because we talk about this like it is some massive change in the way the utility system does business. But I think it would surprise a lot of people to realize we don’t actually require utility companies to study alternatives to big infrastructure projects already, given that the technologies have been at their fingertips now for a decade when it comes to rooftop solar and you’ve got affordable energy storage and lots of other things. Yeah. I just don’t know how to express enough surprise, I think, on behalf of people who aren’t in this business at the notion that we just let them say, “Well, this is the way that we do it.” |

| Anya Schoolman: | As a utility, they get a guaranteed rate of return on every penny they spend. 12% or so. But the builders want to address an incentive problem that also addresses the utility’s monopoly on data. Normally, when you say you’re countering the utility and you’re saying no, you could do a non-wires alternative there, the answer’s always you got your data wrong. You don’t have the right analysis. You don’t have the facts. So, what this is really saying is that there’s going to be essential data authority that anybody could have access to.

Obviously, they wouldn’t have individual records. They couldn’t find John Farrell’s bill and see how much he’s spending on electricity. But they can get system analytics, they can get block analytics, and that means that it’s really forcing open the market for microgrids, non-wires alternatives, alternative infrastructure, peer to peer, all kinds of potential things that fundamentally, the utility holding on to the data with iron fists is what’s preventing … One of the main things, not the only thing, but it’s one of the main things that’s preventing those kind of markets from flourishing. So, the data, it’s like our data and this bill is really saying it’s our data and give it to us. So, that’s really, again, it seems like that shouldn’t be that radical. But in the world of utility and management, it’s a crazy, freaky idea, I think. |

| John Farrell: | I think I feel like I always have a few terms in a glossary I want to introduce people to when I start talking about this kind of utility market stuff. The word “proprietary” comes up. Utilities love the term “proprietary” or “trade secret”, things that are meant to shield information from being shared. I think it’s such a great illustration here, as you say, Anya, about how if that data is available to other entrepreneurs, to the public, that there are so many different ways that we could approach solving the energy issues that we have on the grid.

The utility will say, “Oh, we just need to build a big substation, this big piece of infrastructure.” As you point out, they’ve got an incentive to do so. They make a huge profit on it if they’re able to build that piece of infrastructure. I think that’s what’s so great about this bill is what it says is we’re actually going to look for the solution that’s best for the grid, best for the customer. If that ends up being something that the utility builds for us, that’s fine. Then they can still get their profit on it. But if not, then we have a chance to save everybody money and to be more efficient and to encourage local solutions that create local jobs. So, it seems like a win-win-win. But I can understand why, having fought monopoly utilities in a lot of ways, it can be an uphill fight. |

| Anya Schoolman: | Yeah. We’ll see how this one goes. It’s got a lot of organized support. But it is arcane and it’s hard for some people to understand. Why would you be fighting for this if you’re not already immersed in it? It’s not as easy to communicate to general public 100% renewables or something like that. |

| John Farrell: | Right. I wonder if that’s what some of the beautiful simplicity of, in Nevada, on the ballot next week, they have this question three, which essentially says let’s destroy the utility monopoly and create retail competition. It’s hard because I have to say from my perspective, the reviews I’ve seen of retail competition aren’t always in favor of promoting the social goods we want to see, like energy efficiency or renewable energy. Yet, I can see how people, having watched how the utility acted in Nevada to fight rooftop solar, to end that rooftop solar market and finally seeing it reversed, have a lot of built up anger about it.

So, it seems to me like this is a good compromise, in a way. It’s like instead of going down that road of blowing open the whole market in a very big change, here’s a way that we can incrementally look toward introducing some level of competition in a way that allows the utility to continue to play, but allows innovative solutions as well. |

| Anya Schoolman: | Yeah, and frankly, the data’s important for other thing too, not just infrastructure. For example, D.C. spends over 20 million a year on energy efficiency upgrades and we have a big contract and it’s supposed to lower our total energy use by 1% a year. It’s been going on for six or seven years now and no one can, with a straight face, tell you exactly how much impact it’s had because we don’t have system measurements of how much energy we’ve used. We don’t have a good baseline.

So, we’re doing all these, spending millions of dollars on climate planning and all these other things and nobody has the basic data to measure the impacts of the program. So, there’s a lot of good public policy reasons to do this. |

| John Farrell: | Hey. Thanks for listening to Local Energy Rules. If you’ve made it this far, you’re obviously a fan and we could use your help for just two minutes. As you’ve probably noticed, we don’t have any corporate sponsors or ads for any of our podcasts. The reason is that our mission at ILSR is to reinvigorate democracy by decentralizing economic power. Instead, we rely on you, our listeners. Your donations not only underwrite this podcast, but also help us produce all of the research and resources that we make available on our website and all of the technical assistance we provide to grassroots groups.

Every year, ISLR’s small staff helps hundreds of communities challenge monopoly power directly and rebuild their local economies. So, please take a minute to go to ilsr.org and click on the donate button. That’s ilsr.org. If making a donation isn’t something you can do, please consider helping us in other ways. You can help other folks find this podcast by telling them about it or by giving it a review on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. The more ratings from listeners like you, the more folks can find this podcast and ILSR’s other podcasts, Community Broadband Bits and Building Local Power. Thanks again for listening. Now, back to the program. I know that policy work is only one leg of the stool for Solar United Neighbors. I’d love you to talk a little bit more about how is it that you bring people into the fold and get to talk to them about policy? That’s usually not the first thing that you’re talking to them about. I’ll just say again as a thing of disclosure, I’m not only a volunteer board member, but I’m a participant in a solar co-op in Minneapolis right now- |

| Anya Schoolman: | Oh, that’s so exciting. |

| John Farrell: | … the Minnesota Solar United Neighbors division. So, we’ll be hopefully getting solar in my house next week as part of participating in that group purchase. I do have to say, I feel a little bit like those old Hair Club for Men advertisements, right? I’m a participant. I’m not just the president. |

| Anya Schoolman: | Yeah. So, we have gotten about 3,000 people, helped them go solar. The numbers change every time I talk, so I always forget them. I know it’s more than 26 megawatts of rooftop solar. We’ve added a bunch of states, so this year, we added Minnesota and we added Pennsylvania and we added New Jersey. That was real excited. We’re just about to add three more states. So, we’re adding Texas, Indiana, and Colorado.

We’re still fundraising to try to fill out the funding for the programs, but we’re pulling the trigger. So, we’re super excited about it. We’re doing co-ops in all those states. I think, was just talking to Aaron Sutch, who’s our Virginia program director, and he said that they’ve done almost 30 co-ops in Virginia since he started. |

| John Farrell: | That’s amazing. Now, could you just walk us through really quick, what does a solar co-op look like, how does it get organized, and then what are people trying to do together? |

| Anya Schoolman: | Sure. A solar co-op is, to some people, might have heard of Solarize, and it’s similar, but it’s different. So, it’s a group of people that gets together. We help organize them, but we almost always are working with a community partner. We help them go solar from beginning to end. What we do is do the education, screen the roofs, teach people about solar, answer 10,000 questions, have community meetings, get together. Then when the group forms, we issue a single RFP for one installer for the whole group.

Then we work with the installer to make sure people are getting really good service. Sometimes, that means going to the permitting authority and getting something fixed or going to the utility to get the interconnection. So, all the way through, all the things that make solar sometimes complicated, we address as a group with group power to address that. It really makes a difference in terms of building markets. So, that’s the basic process. We’ve also started a new offer, in which it’s just single memberships. So, if you live in a state or a location where there’s not a co-op, we can support you. You have to pay because then we can’t afford to do it all for free. But it’s an $85 membership. You sign up and then we basically handhold you through the process. So, it’s like a mini version of the same thing. |

| John Farrell: | That’s awesome. I think one of the things that’s great about it is not only are you helping individuals walk through something that is new to them, different from buying a car or other thing like that, if nothing else, it’s one of the few things you’re ever going to put on your house that will make you money back is what I keep telling people. But I think one of the other things that is exciting about it from more of the solar energy market perspective is that when we talk about the cost of solar and people want to keep driving down the cost of solar, this is one of the great techniques for it because of course, one of the big costs that I keep seeing talked about for the solar companies is finding customers.

Here, Solar United Neighbors can not only help them find customers, but help their customers understand some of the basic issues around solar before the installer even has to have a conversation with them. |

| Anya Schoolman: | Yeah. One of the reasons that our approach works, that we think it works a little better than the Solarize model is that we are organizing customers in a fairly tight location and we usually do it in consultation with solar companies. So, is it one permitting authority or how far would you drive? So, we try to get a perimeter that makes sense for a company to optimize their costs. Then we screen the roofs and educate the customers. So, by the time we’re giving a group to a solar installer, it’s a very winnowed down group. It’s people that have good roofs that they’re in good shape, that know what the cost, that know what they’re getting into.

So, they have a very high close right. They close usually 35% of the leads that they get from us. So, that saves them, usually it costs an installer about $3,000 per person to find a customer. So, that’s saving them a lot of money and a lot of those savings get passed on to the homeowner, depending on the market and stuff. |

| John Farrell: | So, we’ve walked through the way that people can participate, the way that they can get solar on their roof through Solar United Neighbors. We talked at the beginning about energy policy. Now let’s connect the two a little bit because that’s one of the things I think that’s so brilliant about this model, speaking as a board member, is this notion of how we take people who are participating in the market and doing some exciting for themselves and get them engaged in the broader public policy discussion about clean energy. |

| Anya Schoolman: | Yeah. So, we start at the beginning. So, if you go solar with an installer, they’re going to skip the policy stuff. They’re going to skip all variables and they’re just going to be like, “This is what it costs, sign here. I’ll make it easy,” and they don’t want to get into the details because they don’t want to scare people away or get them bogged down. What we do is really deliberately educate people about what the market is and how it works right from the beginning.

So, when we present about solar, we don’t just tell them what it costs. What we say, this is what net metering is. This is the policy that enables you to get compensation for your excess generation and how it works. This is how it works in your state and this is how it works in other states. We talk about interconnection, we talk about RPS, we talk about all the value and all the policy that impacts them. So, by the time they’re done going solar, they’ve been introduced to a lot of new concepts. Then we stay in touch with them. So, we have a monthly newsletter for each state where we’re working that tries to keep up to date on cool projects, things that are happening, Solar 101, but also big policy developments. Then we do the advocacy, like a lot of other groups. But we really do it from the perspective of the solar owners. So, what do you care about? What impacts you? What’s going to motivate you? Then we also work with a lot of volunteers and have the volunteers directly educate their elected officials. So, they’re often meeting with, sending emails, sending pictures to their congressman or their city council member, their local legislator and saying, “I have solar. It saved me money. This is why it’s important to me.” So, we really build a feedback loop that really empowers a lot of people to have a really high level of impact on building this rooftop solar revolution. |

| John Farrell: | One of the things that I was curious about in the way that you work, since it’s very different, I feel like, from a lot of the policy groups that approach this from more of an environmental perspective, do you feel like you have seen any kind of conventional wisdom about working in solar energy overturns, some interesting alliances that you’ve made in your work that don’t seem as common when you come at this from a climate or an energy or environmental perspective? |

| Anya Schoolman: | Well, one of the thing, we don’t talk to people about why they want to go solar at all. We never try to convince them to go solar. We just start from the premise that if you’re talking to us, you already want to go solar. It turns out that’s true about 90% of Americans anyway. So, we never talk about values. We have people bring their own values to the process. Because we’re very pragmatic, and very action oriented, it’s a place where, for example, in West Virginia, we have people from the oil and gas industry and the coal industry participating in our groups and they’re really excited about it.

They’re energy people, often they’re engineers, maybe they care about the impact of their job on the environment, they want to do something. Whole range of values. Maybe it’s just saving money in private property. But because we really create room for a whole range of values to come together, we get a lot of just interesting alliances and networks of people. I think it helps underscore the pragmatic aspect of solar, that it’s like there’s no reason not to do it, I guess. |

| John Farrell: | Right. So, I wanted to finish up with a question for you about, we’ve been doing this Voices of 100% special series in our podcasts where we’re talking to elected officials and we’re talking to grassroots advocates in cities that have made commitments to get to 100% renewable energy, sort of like D.C. is considering with this legislation.

I’m just curious, what advice would you have for them about reaching that goal? Because you’re on the ground implementing. You’re talking to people every day who want to go solar, who want to do something that would help reach that goal. What practical advice do you have for people who are approaching this? They’re at the visionary stage. They maybe haven’t really wrestled yet with what are the particulars of how to get there. What do you see as the route for them to be successful? |

| Anya Schoolman: | I don’t know if I have good advice on this. I do think that you really have to be serious and real about the impact on people’s bills. You just can’t pretend that energy’s free or that going to 100% doesn’t cost money. So, equity is really a serious thing that needs to be taken seriously in a number of ways. It needs to be taken seriously in terms of who’s at the table, who gets to weigh in on it and help design the program, and also in terms of programs that you set up that mitigate impacts if what you’re doing is going to raise bills.

So, I think that’s the most important thing is really being, not getting too idealistic and really staying more grounded in the pragmatic, who does this impact and how and trying to figure out, there’s so many solutions now on the table as the cost of renewables and storage and all that have gone. There’s so many win-win solutions on the table. So, being real and pragmatically embracing, what’s the impact going to be, and therefore, what’s a pragmatic solution and not be in the ideological realm where people tend to get polarized. |

| John Farrell: | You said you didn’t have good advice, but that sounds like terrific advice to me, Anya. So, thank you. Thanks again for taking the time to talk with me. It’s always a pleasure to have you on the podcast. |

| Anya Schoolman: | Yeah. It’s delightful to talk to you. Thanks a lot for inviting me. |

| John Farrell: | This is John Farrell, director of ILSR’s Energy Democracy Initiative. I was speaking with Anya Schoolman, executive director of Solar United Neighbors, about two pending clean energy policies in Washington D.C. and how Anya’s organization helps folks go solar and connect with the policies to defend solar rights. You can hear two previous interviews with Anya in our Local Energy Rules archive at ilsr.org.

You can hear about other communities taking the 100% renewable energy plunge in our Voices of 100% special podcast series and see them on our newly upgraded company power map. While you’re at our website, you can also find more than 50 past episodes of the Local Energy Rules podcast. Until next time, keep your energy local and thanks for listening. |

100% Renewable Energy by 2032?

The first part of the conversation covered two big policy proposals in front of the D.C. city council, starting with a 100% renewable energy commitment by 2032. Anya emphasized that the plan seems more ambitious than at first blush:

“In some ways it’s not very aggressive at all because DC is kind of a very small island within the larger PJM. We could actually decide to go 100% tomorrow, because there’s enough renewables in the grid, and enough RECs around. You could just do it. It wouldn’t even be that expensive…The devil’s in the details.”

It’s a juicy debate: Should the 100% commitment result in new renewable energy deployment? Should it be local energy? Can you buy renewable energy credits from Texas? Does the District still need investments in energy efficiency if electricity is 100% renewable? (John and Anya had a few thoughts on the benefits of energy efficiency and local energy development that persist even with 100% renewable electricity). Interestingly, the debate has been more into details than the goal itself, about which there’s significant agreement.

Few advocates want to take a shortcut to 100% renewable energy. Instead, the debate has centered on how the 100% bill will align with the District’s existing commitments to reduce energy use and to increase low-income access to solar energy. The Solar for All program, for example––the centerpiece of the District’s focus on energy equity––requires D.C. to build local rooftop or parking local solar sufficient to cut the energy bills of every single low-income customer in DC by 50% by 2032.

John noted that several utilities in other regions have proposals to go beyond 50% renewable electricity already, but that the models include centralized, utility ownership that limits the local economic benefits (and doesn’t necessarily save money). Anya emphasized that thousands of local jobs hinge on the debate, but she’s confident that policy makers will retain the focus on local:

“D.C. is going to do what’s best for the people who live in D.C. We have the luxury of being a city-state, so it gives us a little more democratic control over what happens…D.C. has eight wards and all eight wards want local, rooftop solar.”

De-Monopolizing With A Distributed Energy Resources Authority

“It’s a radical bill and it’s meant to be,” says Anya, because of the “slow as molasses” pace of the grid modernization process. Catalyzing the bill is an Exelon-proposed project near the Mt. Vernon Square metro station. The “utility is proposing to build a big substation on top of a neighborhood community garden.” The D.C. Dept. of the Environment has paid for non-wires analysis showing it’s cheaper and more resilient. This new bill would require a similar analysis for any utility infrastructure project costing more than $25 million.

This policy may sound radical to people familiar with grid planning, noted John, but may sound almost banal to utility customers that would expect public regulators already require the lowest cost method of meeting system needs. Anya explained that when the utility makes a nearly-guaranteed 12% return on money invested in infrastructure, it has little incentive to examine alternatives. The Distributed Energy Resources Authority would remove the utility (and its conflict of interest) from the planning process by taking bids for the best solutions to grid needs.

The Authority would play another important market-opening role: sharing anonymous, aggregated electricity system production and use data. Anya noted the significance of the bill:

“The utility holding onto the data with iron firsts is…one of the main things that’s preventing markets from flourishing…This bill says it’s our data and give it to us…it shouldn’t be that radical.”

Anya emphasized that this benefits advocates that have long played at a disadvantage when challenging utility proposals: “When you’re countering the utility, the answer is always ‘you’ve got your data wrong.’” The Authority’s openness with data would also ensure that non-utility companies could make effective counter-proposals to utility infrastructure upgrades. Finally, the data will help the District effectively evaluate its $20 million per year energy efficiency investments:

“It’s been going on for six or seven years now, and no one can, with a straight face, tell you exactly how much of an impact it’s had.”

The bill has a lot of organized support, says Anya, but it’s arcane. It’s not as easy to communicate to the general public as 100% renewables.

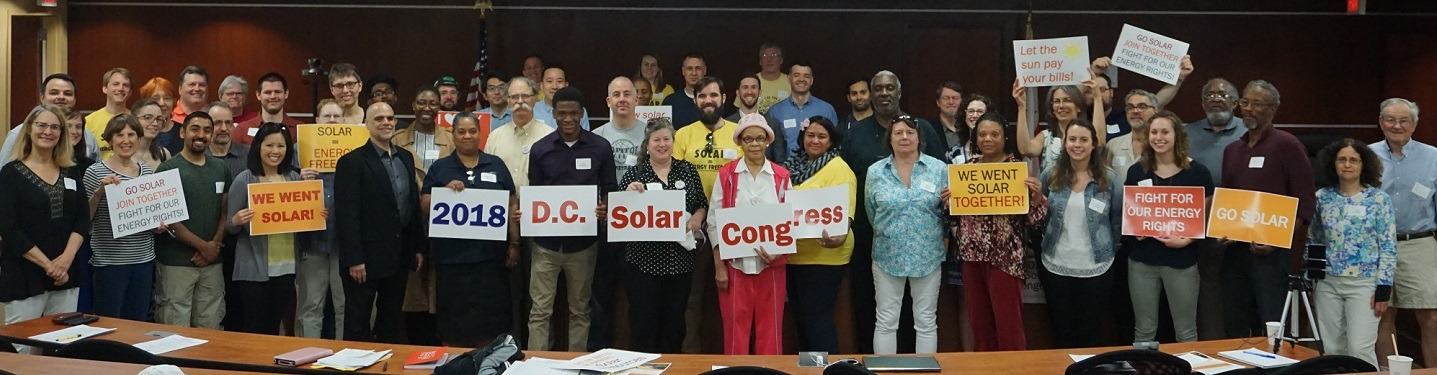

The Pipeline to Policy––Solar United Neighbors

Solar United Neighbors (SUN) has been building more than a couple good policy ideas in D.C. The organizer of solar buying cooperatives has now served over 3,000 customers that have installed a collective 20 megawatts of solar. In addition to six states already served, solar co-ops were launched for the first time in Pennsylvania, Minnesota, and New Jersey this year, with launches planned in Texas, Indiana, and Colorado in 2019.

The strategy is simple. Group solar people together to simplify the process of identifying an installer, smooth the permitting process, improve customer service, and negotiate group discounts.

“All the things that make solar complicated, we address as a group…by the time we’re giving a group to a solar installer, it’s people that have good roofs…know what they’re getting into…usually it costs an installer $3,000 to get a customer…a lot of the savings are passed on to the customer.”

For individuals outside the area served by SUN cooperatives (or that already have solar), it’s possible to receive similar services by joining Solar United Neighbors for a fee.

The cooperatives build on the relationships established in the process of going solar to talk to members about policy. In fact, unlike most installers who are focused on closing a deal, Solar United Neighbors explains the policies behind the solar opportunity––like net metering––from the beginning. They help solar owners communicate their solar interests to elected officials and build community.

The secret sauce to Solar United Neighbors may be in the agnostic approach to solar.

“We don’t talk to people about why they want to go solar…we have people bring their own values to the process…we’re very pragmatic. In West Virginia, we have people from the oil and gas industry and the coal industry participating in our groups and they’re really excited about it…it underscores the pragmatic aspect of solar––there’s no reason not to do it.”

Advice for Ambitious Cities?

John wrapped up asking Anya what advice she has for cities that are pursuing 100% renewable energy goals. Her main point was to avoid being too idealistic:

“You really have to be serious and real about the impact on people’s bills…equity needs to be taken seriously…in terms of who’s at the table, who gets to weigh in and help design the program, and programs set up to mitigate impact in terms of bills.”

Despite the need for pragmatism, Anya says, there are so many win-win solutions on the table. Her organization will be out helping people find those win-win opportunities, now in 12 states in 2019.

This is the 64th edition of Local Energy Rules, an ILSR podcast with Director of Democratic Energy John Farrell that shares powerful stories of successful local renewable energy and exposes the policy and practical barriers to its expansion.

This article originally posted at ilsr.org. For timely updates, follow John Farrell or Marie Donahue on Twitter, our energy work on Facebook, or sign up to get the Energy Democracy weekly update.