Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Economics writer Brendan Greeley has a thought about the role ‘economics’ play in our politics: “economists think that they’re physicists, but they’re actually just sociologists watching things and observing them“.

To suss this out, Building Local Power hosts Christopher Mitchell and Stacy Mitchell sat down with Greeley. He is a writing alum of Bloomberg and The Economist and currently writes his daily economics newsletter, All We Know So Far (subscribe at the link).

“I think the thing we’ve lost sight of in America is that we don’t understand that healthy competition creates all the things we love about capitalism. The irony of that is businesses don’t like competition. They hate it. It drives them crazy. They can’t do what they want. And so the most successful businesses will do everything they can to avoid healthy competition,” says Brendan Greeley of the issue he is trying to solve in his All We Know So Far work.

Our guest recommended the following items:

- Debt: The First 5,000 Years by Henry Graeber

- ProMarket Blog: The blog of the Stigler Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business

- The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine by Michael Lewis

- The Big Short film

Related Resources:

Institute for Local Self-Reliance: Monopoly Tag — All of the stories tagged with “monopoly” on our website details the — mostly — unchecked power that vast corporations and firms enjoy in our economy and democracy. Get the latest information on monopoly power in retail, broadband, energy, and waste stream issues.

Institute for Local Self-Reliance: Monopoly Tag — All of the stories tagged with “monopoly” on our website details the — mostly — unchecked power that vast corporations and firms enjoy in our economy and democracy. Get the latest information on monopoly power in retail, broadband, energy, and waste stream issues.

Podcast: The Rising Anti-Monopoly Movement (Episode 36) — ILSR experts Christopher Mitchell, Stacy Mitchell, and John Farrell sit down to tackle the reality of increased corporate consolidation in the economy and what it means. They also knit together their research focuses and connect them into how an anti-monopoly movement is brewing where everyday Americans are standing up and saying “enough”.

Podcast: Beating the Monopolies: Barry Lynn Explains How We Will Win (Episode 30) — This podcast episode with the Open Markets Institute’s Barry Lynn discusses how we got to here in our monopoly economy and how he has hope that we will win against the monopolists who are robbing our political economy.

Policy Brief: Comcast’s Anti-Municipal Broadband Election Investments — In the Fall of 2017, this ILSR analysis details just how much money telecommunications giant Comcast Corporation is pumping into its efforts to scuttle pro-Internet access competition efforts in Fort Collins, Colo. and Seattle, Wash. Why? Because if these communities actually attained some measure of competition, Comcast could lose millions.

| Christopher Mitchell: | Welcome everyone to another episode of the Building Local Power podcast from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. I’m Chris Mitchell, once again having commandeered the hosting position for this show. We have Stacy Mitchell, one of our regular hosts, back on.

Hi, Stacy. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Hi, Chris. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Stacy directs the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, and I run a program on internet-type broadband access improvement-type stuff.

Today, we’re talking with Brendan Greeley. Welcome to the show Brendan. |

| Brendan Greeley: | Thanks, guys.

I would say thanks to Chris who I like to think of as an internet friends because we tweet at each other, but I remember that we met each other a very long time ago before we were internet friends. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Right, and that’s something that I hope to get to at the end, which was one of my favorite stories, which I still google on a regular basis from when you were a staffer at Business Week, which was a story entitled Pssst … Wanna Buy a Law?, and it pulls it up every time from 2011.

But you, more recently, you do an economic research note called All We Know So Far, which I really enjoy. I have to note your Twitter feed’s a little behind because I wanted to share the most recent one, but I’ve not been able to yet. |

| Brendan Greeley: | Oh, you know what? Actually, I borrowed some of that data from other economic research notes, and I felt okay putting it in the note, but I didn’t feel okay putting it online. I didn’t want to tempt fair use. I felt that I was within the bounds of fair use, but sometimes you shouldn’t poke the fair use bear. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Well, it was very good, and it was about where the money from the tax cuts are going, and how that’s okay, but it was very well done. I encourage people to check it out because it describes itself as an economic research note for people. And as a people who has taken macroeconomics but struggled through it, I can say that this is for people, and it’s helpful. |

| Brendan Greeley: | Thank you. The great irony is that I too struggled through macroeconomics. No, actually, got a good grade in macroeconomics. I struggled through micro, but I haven’t actually taken any macro or micro anything since. I do not have a degree in economics. I have a degree in German literature.

I do think, and this is to our broader conversation today, one of my frustrations when I became a correspondent who wrote about economics was that so much of what we remember from school is not really true. If you got a degree in economics or if you took micro and macro in college in the ’80s, or the ’90s, or the early 2000s even, everything you learned then is not really … it’s only a framework that is missing details. Sometimes, I think when we talk about economics more broadly we’re all horrendously misinformed because a lot of stuff has come up, particularly since the recession we’ve learned a lot. Before the recession, there was some experimental research being done that has been borne out by the actual empirical data we have now. So it’s almost as if, when we look at economics, it’s as if we are studying biology as a culture, but we don’t know that it’s possible to sequence the genome. We’re that far behind in economics. And so, one of the things that I’ve noticed is that economic research for people in finance is very good. It tends to be pretty good because if you get it wrong, you lose even more money. So I’m trying to take that spirit of being completely on top of things for finance and bring it to citizens as well because we tend to be misinformed about economics for a ton of reasons. But I think the debate over economics is much worse than the debate over climate, and the reason it’s much worse is I don’t think most of us even know how polluted the atmosphere is, how little what we’re talking about resembles the cutting edge of the actual social science. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Yeah, I think that resonates with me. I’m very curious to ask Stacy whether she studied economics. Just before we get into the actual meat of the discussion, this is actually a lot of what we’ll be talking about, I think, how the economy works, our understanding of it, how to make it work for more people.

Stacy, before I find out how you did in economics, I just want to say I did really well in micro. I really liked micro. I found that it actually is somewhat useful mostly because it’s a really great idea that seems never to be really particularly practical, but nonetheless, it’s sort of this ideal that I can understand how some people might think things should work even though they don’t because of obvious discrepancies. But, one of my challenges with macro is that I was on Percocet for most of it because I’d had a major surgery. And three courses in a row and I had to take a Percocet in the middle of the first one, and I would be riding that halfway through the third one. Macro is mostly gone because of this surgery I was recovering from, so it was bad timing, and I blame that. Stacy, how did you do in economics? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | You know I dipped into economics class and a little bit in college, but mostly I sort of decided based on that experience that it wasn’t really going to answer the questions that I have. So I went and moved to history and studied, actually, labor history, which I found to be a good way to understand the economy, particularly how it’s changed and how people can change it through policy. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Yeah. |

| Brendan Greeley: | I think that’s really interesting, and I think that one of the things, and then Chris I promise I’ll let you move onto the thing you actually wanted to talk about, is that you know there’s this idea that economics should inform other social sciences. You know there’s this Freakonomics idea that the things we learn about, human motivation, can be applied elsewhere. What I think that misses is that economics every time it takes in another social science, it gets better. You know people like Daniel Kahneman and Richard Taylor who won their Nobels for behavioral economics, Robert Shiller they took in the lessons from psychology, and it turned out that it helped them understand their actual profession better.

Often, I talk to … I like to call sociological economists or anthropological economists … or, sorry, economic anthropologists because they study the way we use money as groups of people and that turns out that all those traditions about how we use money are every bit as important as the marginal cost benefits that economists would have us calculate. So I think that there’s a lot missing when we just talk about economists. And I think you’re absolutely right, reading back in history longer than the Great Moderation helps us understand a lot of the things that we’re experiencing now as we look back to the late 19th, early 20th centuries. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Right. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | I’m curious, Brendan. You mentioned that you think since the financial crisis that our understanding of economics has really changed in fundamental ways and maybe behavioral economics you sort of intimated just now maybe is one of those ways. But I was going to ask you; I’m kind of curious what you think some of those big shifts have been? |

| Brendan Greeley: | Yeah, I think the biggest one is something that economists call heterogeneity, and that’s a really fancy way of saying people are different. To make the math easy … Yeah, it’s true. It sounds insane that we didn’t know this already, but economists are sort of just learning this over the last five years or so.

So a lot of … Most economic models rely on a single agent. Sometimes that single agent is also immortal. Right? So, we’re assuming there is one person in the economy making decisions and that person will never die, right? So we’re modeling on somebody who’s god, and that’s not how the real world works. So when you start to build models that have two or three different agents in them, people who are motivated in different ways, you start reflecting the actual economy and the way people respond, in a more accurate way. I’ll give you a specific example of what I’m talking about. People who have access to credit behave differently than people who don’t have access to credit. So if you have access to credit, you’re not really worried about the present because you can borrow in the present to sort of meet your needs. And so for example, we carry out an austerity policy. The old models didn’t really think about who had access to credit, who could borrow money or not. They assumed that everybody had access to credit because there is credit in the economy and economists have access to credit because they have excellent credit rating scores. Who doesn’t have access to credit? And so they assumed that in an austere policy gives you confidence about future returns and you base your own decisions right now about future bond market prices in the country that you live in. That’s perfectly rational for an economist. It’s not how any of the rest of us actually think. When you model people, who are wealthy and have access to credit and people who are not wealthy and don’t have access to credit they respond very differently to austerity. It turns out that if you add a little extra money to the economy people who don’t have a ton of money will spend that money immediately. You get very different results. And so the IMF actually apologized. You know, when the IMF imposed its austerity program on Greece the IMF didn’t want to do as brutal an austerity as Germany did. But the IMF looked at its results and discovered that Greece was not thriving, right? People were not responding as predicted. They did not suddenly feel more confident in future bond prices for their economy and future tax policy [crosstalk 00:09:39]. They felt awful because everything had been drained out of the economy, and nobody was spending any money because nobody had any extra money, and nobody had access to credit. Right? So, this stuff makes sense intuitively, but the models are very complex, and they make a lot of assumptions. The assumptions, I don’t think they’re maligned, but they do tend to be the same assumptions that economists have for themselves. Right? We model the world. We remake the world in our image. And so that for me is the biggest distinction, which is that if you think about different people responding differently to the same stimulus you get a very different policy prescription, in some cases, massively different. And so this is stuff that we just didn’t think about before the recession. We just didn’t think about it. I think that economists are recognizing that finance place an important role. Economists used to be disdainful about finance. They thought it was this sort of dirty thing that happened in London and New York and they didn’t have to really about it. They were in Chicago, or Berkeley, or in Massachusetts and you know things were going to be financed however they needed to be. And so long as there was the same amount of capital in the economy how it moved around was not really important for their model. Of course, that turns out not to be true. You can allocate capital in very destabilizing ways. And so the Fed actually had to teach itself finance. You know starting at about 2010, so it could figure out what it had gotten wrong. So economics is changing. The problem is our popular perception of economics is not changing. And so I don’t think that the recent tax policy was a smart move, the changes that we made. It’s not because it was a mean, it’s because there’s very little, in fact, there’s zero empiric evidence that says it will work, and there’s a ton of empiric evidence that says it won’t work. And so what you have right now in economics is actual experience. You have economists who have used data of things that actually happened, and they are fighting against a much older kind of economics, which makes assumptions about things that will happen. And those two economics are fighting right now. The kind of economics that says, “cut taxes, and they’ll pay for themselves,” that’s not born out with any actual empiric experience of the real world. It’s a thought experiment from a blackboard from 40 years ago. But there’s certain people who want to do it that way and so that why we end up having this fight. Anyway, the short version of all this is that economists think that they’re physicists, but they’re actually just sociologists watching things and observing them. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Well, and I think one of the things that I think about when I’m about to rage-tweet about something regarding economics, and economists, and the Chicago school or something like that, I send that [inaudible 00:12:24] to pause to remind myself that most economists don’t think like the Wall Street editorial board. Despite the fact that- |

| Brendan Greeley: | None of them do. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Well, exactly, exactly. And sometimes I get this, I’m like, “Oh, these economists are just so arrogant, and this, and that.” And I have to remind myself, no those are just the ones that have a megaphone, and they have a megaphone for a very specific reason because they are serving the interests of the people that can afford to have lots of megaphones it seems like. |

| Brendan Greeley: | There’s such a small number of people who do this for a living, really small who write for the Wall Street Journal editorial board. I’m coming up with a term for this.

But there’s the academic profession of economics, which is fascinating and varied, and people are having really honest and open discussions about data, this huge movement towards using bigger and better datasets, more computers. They are trying to figure out what they got wrong, and they’re not doing a terrible job of it. Right? If you go to the American Economists Association Conference, I go every year, there are really vibrant, fascinating discussions about how to get this right in the future. Then we have this parallel discussion of something called “economics,” which is a thought process from about 40 years ago, and that’s the one we legislate by. I don’t know what to call that one, but it’s driven by think-tanks in Washington. It is not driven by academics, and there are a small number of people who have academic degrees, who work in those think-tanks, and they’re the ones … It’s really like five people who write all of these op-eds who actually have PhDs, a very small number of people. And they’re a very small minority within the profession of economics. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | We brought this up in a show back, beginning of January, I think, about Paul Krugman had called them the difference between conservatives who are professional economists and professional, conservative economists, the latter being that small group of people. |

| Brendan Greeley: | I think that’s a good distinction. I think Paul Krugman himself has some things to answer for.

Stacy, you asked earlier what are some things that are changing about economics. I think the other thing that is changing is economics for a very long time relied on the mean, they relied on aggregate numbers, and there’s no such thing as an average person. We all do things differently. It turns out that the distribution of the effects of a lot of things that happen in economics are really painful and very targeted. So when you look at things like immigration, yeah, it’s really good for an economy overall, but it can be very expensive for certain, targeted populations. It turns out schools in areas with a lot of immigration end up being strapped for funding. So I think it’s very easy … It has also been easy for left-wing economists to say, “Look, immigration is good.” Of course, it’s good in the aggregate, but ignore the distributional effects. I think trade is another one. Paul Krugman has always been a strong proponent of trade. We’ve only had the data and the incentive to look at trade having very bad consequences in very specific areas. You know, none of us thinks of ourselves as the average person. We’ll all think of ourselves as a certain person who is doing a certain thing in a certain town, and if that gets taken away because of trade, we don’t really feel any better that the country as a whole is better off. And so I think that another thing that economists got wrong, that economists, by the way, are fixing but politicians haven’t quite figured out yet is that things that are good for all of us, in general, are often bad for some of us in specific. There’s no politics to address that thing that economists have slowly faded out. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Well, this is something that Stacy has talked about before on the show. And that’s, I think this is relevant, which is that you may take a person who runs a store, a local retail store, and that person … Let’s say that store is driven out of business in part because of Walmart, and that person goes and becomes a manager at Walmart. I think a lot of economists might think, “well, that community is simply the same. Maybe it’s better off for having lower prices for certain items from Walmart.” I’m not going to say anything about the quality of those things or other impacts. Whereas, we look at that, the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, and we say that’s a community that’s in some way’s lost some leadership. It’s lost some prestige. There’s different impacts that have not historically made it into the equation. |

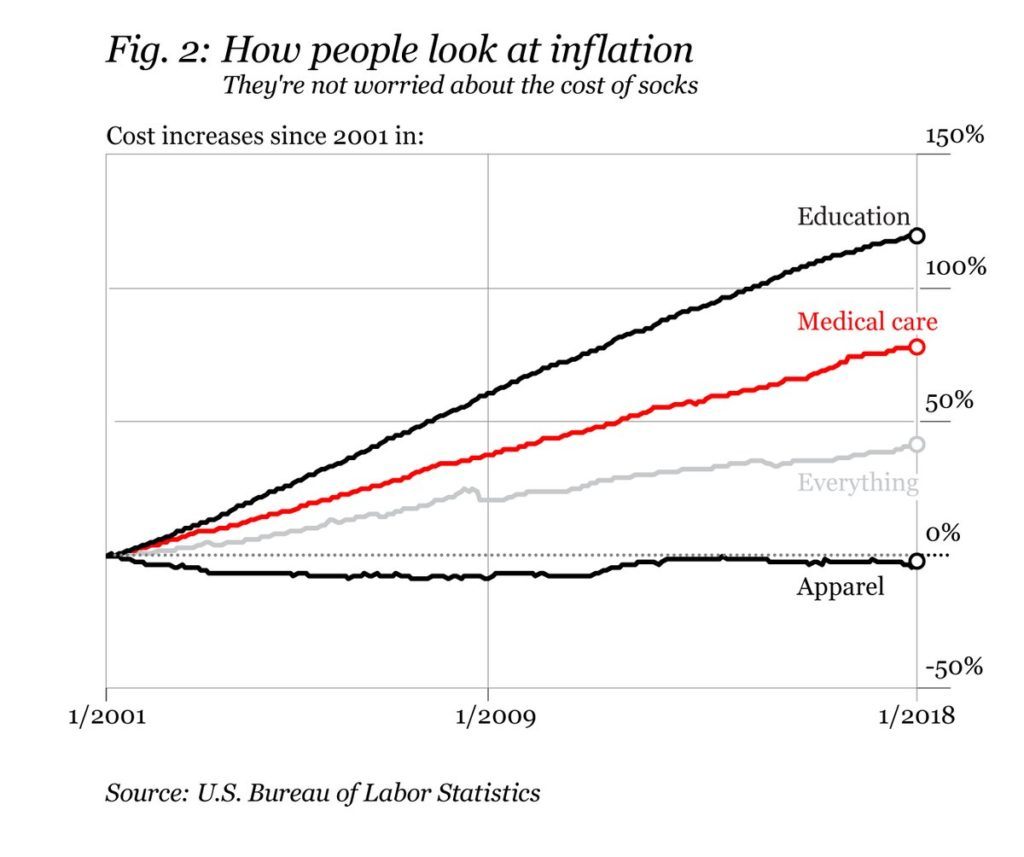

| Brendan Greeley: | Yeah. I think it’s a tyranny of measurements. I think we’ve chosen a few things to measure, and we’re learning that we were measuring the wrong things. Maybe we weren’t measuring the wrong things. Maybe it’s that systems adapt to create what’s being measured, so if what we’re creating is low consumer prices, we did a great job. But, one of the things that we’re recognizing is that even though inflation is down, it’s up a ton in a couple of things that we really care about, healthcare and education. So, even though we’ve done a really good job of managing inflation in the aggregate, our socks are a lot cheaper than they used to be, our TVs are a lot cheaper, so is our furniture, but the stuff that really matters that helps us flourish is not cheaper.

And so to get back to specifically what it was that you got in touch with me about, you had this idea of monopoly, you know, we changed what we were going to measure. In the early ’80s we decided it was no longer necessarily true that monopoly in and of itself created restraint of trade, it prevented new entrance, it drove down labor prices. It has a bunch of bad consequences. We thought, well the only thing we really care about is consumer prices, so if we can prove that consumer prices are going down then monopoly is okay. And so we measured that, and it kind of works, and it turns out to have had all sorts of other consequences. That’s a discussion that I only just now see moving into, I wouldn’t even call it the mainstream, but it is moving into policy circles and out of economic circles. The word, monopsony, a single buyer of labor was something that you only heard in academic papers starting about two years ago. They started to think, “Well, what’s going wrong? What’s going on? It might be monopsony. You think?” And now, it’s starting to show up in think tank papers, which is a real improvement. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Yeah, one of my colleagues actually corrected a paper in which I had written, or some blog post or something, because she thought that that was not a term. She had never come across it before. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Brendan, I love this phrase that the tyranny of measurement that you used. I’m really struck, as a lot of people are now, by how different the economy feels for many Americans than what is reported in the numbers. I mean, I think many Americans feel very precarious in their economic situation like they’re working a lot, struggling to their heads above water, and yet we’re in … You know we’ve had … We’re in an upswing in terms of being in a real sweet spot in the economic cycle, and you know stock market has been soaring and so on and so forth.

You know, when you look out there I’m curious what you see in terms of the economy’s structural issues that aren’t working for a lot of Americans? And I guess as part of that question I’m also curious if you think we’re at risk for another kind of economic or financial crisis? |

| Brendan Greeley: | I don’t think that we’re at risk of something like what we had in 2000 and 2009. Debt crises are worse than business-cycle collapses. Business-cycle collapse is usually what happens is a bunch of companies that had inflated stock prices lose their value, so people feel less confident about the future. They no longer have those companies as buyers, they no longer have those companies in their stock portfolios, even their 401(k)s, the half of Americans who have 401(k)s, and so they buy less. Right? So there’s an expansion in hope, and there’s a contraction in hope. That’s a normal process.

What we had in 2008 was a collapse in credit, which is something else entirely, and it was centered around people’s houses. And so when you’re borrowed to the hilt on your house, and you lose it, there are all sorts of consequences. A house is not like any other asset. You know, when you hand off those keys you don’t have a place to live. It sounds obvious, but that’s a much bigger deal than declaring a bankruptcy on your credit cards. So I do think that most of the economic indicators that we see say that we are on the backside of this expansion, but not that there’s a recession looming around the corner. But there’s one coming in the next two or three years. To answer your question about what still feels wrong about this economy, I think if we look back over the last 20 years we have been in a process of replacing wages with credit. We can talk about why wages aren’t growing, but wages are not growing. We’ve seen very little growth in the last 20 years. Median income in the US has been in the mid-50’s. I think it’s $57,000 now, this year, for a household, for decades now. And you know, we’re animals. We’re apes with thumbs. We’re not rational. When we see other people around us getting richer, and we are not we get resentful, and so we took that missing wage growth and replaced it with debt. So before the crisis, that debt manifested itself in very expensive houses and home equity loans. Since the crisis, we have paid down a lot of our household debt on housing, and we have replaced it with car loans, to some extent credit cards, and definitely student debt. So there’s some evidence that debt is fungible, that you can move it around between accounts, that if you can’t get a home equity loan you might, you might, get a student loan instead. Or, you might get a car loan and use that money that you would have put down on a car to pay for something else. And so what we’re seeing is debt levels approaching where they were, but they consist of different kinds of debt. So the good news is, if that collapses people lose their houses, they lose their cars, and they can’t pay back their student loans, that’s not good, it’s super bad news, but it’s not as bad as news as jingle mail where they don’t have a house anymore. So, that’s to answer to your question about the potential for another crisis. The problem is we’ve never gotten rid of the fat. We took all that missing wage growth and we replaced it with debt. We’ve never gotten over that. And so, again, rational economists say, “Well, you shouldn’t live beyond your means.” But, you know, we aren’t rational. We’re people, and so we see a certain standard of living. We see a certain growth in our standard of living, and we when we can’t meet that growth that we came to expect, particularly when we’re told the economy’s booming around us even if we aren’t getting wage increases, then we replace those wage increases with credit. And so that’s your answer, I think. The reason things feel precarious is that debt causes physical stress, and we are at a debt level, fairly recently, I think in the last two or three months, we reached a debt level that is the same as the total debt level that we had as households right before the crisis. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Hey, this seems like a good time for a reminder. We support local businesses and hope that you do, too. Think about that when making purchases and whether you’re helping to centralize power or decentralize it.

We also need your support to do research, to provide technical assistance, and record these interviews. Please donate to help us at ILSR.org/donate. That’s I-L-S-R dot org slash donate. Now, let’s get back to that interview. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | How much do you think this increase in debt, that you’ve been describing, in recent decades was driven by changes in the financial industry? I mean to the extent … Is there a connection between the fact that the financial industry is less composed of local and regional community banks that are really tied in their own well being to the well being of their borrowers versus larger financial institutions that may have more incentive to be loose with debt and push debt? Or does that have nothing to do with it? |

| Brendan Greeley: | So, I’ve looked into the difference between small banks and large banks a little bit. It doesn’t sort out, I think, the way we’d prefer it to.

One of the problems is Dodd-Frank, which I thought was very good legislation. I mean it could have been better if it were simpler, but we just don’t do simple legislation anymore. But one consequence of all that complexity is that compliance costs for small banks rose comparatively. So, if you’re Wells Fargo, you don’t really care about the compliance cost because you’ve got a lot of people already doing that sort of thing and you can apportion it out among your branches. If you run a small bank, lower than a $1 million in assets somewhere out in America, you only have five people in your back office. You add two more to meet compliance and that’s a real expense for you. Perversely, the things that we did to make the system safer have hastened the decline of small banks. That was happening already anyway. Weirdly, there’s a lot of mixed evidence on small banks and loan quality. We find that small banks in rural areas have higher loan quality than small banks in urban areas. I think that the assumption is that might have something to do with that trust ties are bigger in rural areas than they are in urban areas. But I would not lay the increase in debt at the feet of consolidation in the banking industry. I think it is possible to regulate banks in a way that even if we get that natural consolidation that there’s still responsible funding. I do think that what happened is something that we have no control over, but I wish that we would recognize it for what it is, which is that a ton of money is coming into America from other places. You had, at least in the early 2000s enormous oil wealth coming, looking for a place to safely invest, and that place was America. You had a lot of brand new money from China looking for a place to safely invest. That place was America. So we’re sitting with all of these liabilities, all these loans. People just doing anything to buy a treasury debt from the United States. There’s just always a willing buyer for American debt, and that makes you crazy. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Just very briefly, I think people might not get why the fact that there are people with a lot of money outside the United States that want to bring money into the United States may lead to a person like me taking on more debt. Could you just spell that out for a second? And then we are going to get to some of the politics around this, but I want to make sure we make this connection first. |

| Brendan Greeley: | If I show up with a suitcase full of money that I earned in another country and I want it to be safe I’m going to go to a bank. I’ll deposit it at a bank. The bank has what it considers a liability. It’s got my deposit. So I’m a foreigner. So now the bank’s got to go and create some new assets to match those liabilities. The bank considers a loan that it makes to a consumer an asset. So it get these deposits, that’s a liability because it might have to give the deposits back. What it can do is make loans based on these deposits. Right? So money comes in from abroad as a liability, shows up on the bank’s balance sheet. The bank’s got to create assets.

Here’s the problem. There were not enough good, high-quality assets in America to meet the demand that was created by all the liabilities that showed up on banks’ balance sheets. So then, you had this search for any asset whatsoever of any questionable quality. That’s why we got all these crummy mortgages because banks were desperate to get any kind of asset on the books to match the liabilities that they had. One of the reasons why all the German regional banks, all the [inaudible 00:28:34] got caught up in this in 2007 was for a technical reason that I won’t get into. They were about to lose their AAA rating, so they had to go out and create a bunch of assets while they still had their AAA rating, had to with European law. So they got caught up in this too for a completely different reason. If you have a bunch of money coming in, that money wants to make money. Right? You want a return on the money that you’re investing in America, but there just aren’t enough high-quality assets in this economy even though it’s the biggest economy in the world, to create the returns for people coming in from the outside. So that’s a long process. Right? So when we talk about everything that’s happened over the last 20 years, we saw the sub-prime crisis. Right? So that disappeared. And now, you know that money is going to go into other things. One of the things that we’ve seen in the financial markets is that there’s an increased interest in what we used to call junk bonds. Now we call it high yield debt. Basically, there’s not enough high-quality corporate debt to meet all of this money that’s coming in, to become an asset for this money. So they’re moving up the scale to what we used to call junk bonds, we now call it high-yield because more people are interested in it. This gigantic flood of money coming into America funded a bunch of terrible investments. Just the fact that we had the housing crisis didn’t change the flood of money. It just changed the nature and the makeup of these assets that are being created. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | I think that’s a very helpful way to describe some of the pressures. It gets to a different way of thinking about the problem because I think a lot of people think about this problem the same way that led to the establishment of the Tea Party, which the problem was my greedy neighbor, not these larger trends. But I think in some ways, the way that we try to deal with larger trends is by having a political system that has adults in it that are dealing with it.

One of the things that I know I’ve really picked up on your twitter feed and moved you in part from someone that I casually follow to someone that I followed a little bit more closely, so I could respond to you in snarky ways sometimes, was when you made this point that neither political party, the Democrats or the Republicans, and I think we could probably say the Greens and Libertarians also, none of them combine a pro-competition focus with a distrust of big government in maybe overregulation. I’d like you to just talk a little bit about that and how, I think, neither party really has good solution for these issues that we’ve been talking about. |

| Brendan Greeley: | I’m obsessed with the idea of competition because, again, it was one of those things that was missing in economists’ models. You know when we make predictions about what’s going to happen in the future for the economy we rely on these models, and those models rely on certain assumptions. We get so used to using the models that we forget that they contain assumptions. One of the assumptions that these models contain because they were all developed originally in the early ’80s is the assumption of perfect competition. No single company can pay its employees less or gouge its suppliers or gouge its customers because no single company has the market power. They’re assuming that you’ve got a good regulatory state that’s going to prevent that from happening.

So, we don’t have that anymore. We changed what we were measuring. We decided we were going to measure consumer prices, and then we kept consumer prices low, and we allowed monopolies to form. Now we have a situation where the models are no longer accurate. The reasons the models are no longer accurate is companies now have market power to do bad things. What’s fascinating about this, and this is the reason Chris that you and began talking and talk online, is that I started thinking about this problem when I was a tech reporter. I wrote about tech policy, and the reason I moved from tech policy to economics is that I kept on banging up against the exact same problem, which is that tech policy in America is so messed up because we don’t have enough competition. This was insanely difficult to explain to people because I kept on saying, “Prices for all kinds of digital products, prices for fixed internet access, prices for mobile internet access, they’re so much cheaper in Europe.” And people would say, “Well yeah, that’s because they’re socialists. They subsidize them.” And I would say, “No. It’s ’cause they’re capitalists, and they actually create market competition, and market competition drives down your prices, and it also improves your experience.” One of the things that frustrates me is that internet service providers will do all this analysis and say no, prices really aren’t that different here and elsewhere in the world. One of the things that ignores is that the experience is abysmal. Right? They make it really difficult to compare prices. The support is awful. You know when I tried to change something with T-Mobile, which is one of the more benign of the carriers we have in America, they got a fast-talker on the phone to try and shame me out of the change that I was going to make. This is not things that happen in competitive markets because in competitive markets people are scared of pissing off their customers. And so, my frustration, you know, I guess seven years ago when you and I first started talking was that I couldn’t do anything about this industry that I was covering because there was much a bigger problem. Which is that the industry that I was in and covering was so crummy because we have a bigger problem in America. Which is we don’t know how to think about competition. Democrats don’t tend to think about that. They think about fairness. Is the economy fair? Does everybody have a fair shake? They just don’t have a framework to think about it. Republicans think, “well if businesses want something then it must be good because businesses want to make profits, and they want to compete.” That’s just not true. That’s the frustrating thing. I, again, I don’t even think it’s malign-intent on the part of the Republicans. Let’s give them the benefit of the doubt. They want commerce to go forward. I think the thing we’ve lost sight of in America is that we don’t understand that healthy competition creates all the things we love about capitalism. The irony of that is businesses don’t like competition. They hate it. It drives them crazy. They can’t do what they want. And so the most successful businesses will do everything they can to avoid healthy competition, but there’s no framework for that. I keep talking to my friends who actually are in politics that I want to start a party called the Markets party, or the Competition party. They always say, “You’ll be lonely.” ‘Cause there’s no way to talk about this stuff. That’s what drives me crazy. So the thing that you follow so closely, the market for internet access, is crummy for the same reason that so many things are crummy because we can’t talk about competition in this country. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Competition is miserable for businesses. You stay up late at night. I run a small business, and I’m not even in a particularly super competitive industry, and it’s not even something where if I lost my business my family would miss a meal or anything. But nonetheless, I worry about losing clients, and it’s nerve-wracking, and hard. I just want to note that we have to keep that in mind when we’re talking about a more competitive economy. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Yeah, I mean I think you see small businesses actually, you know the ones really sweating it to compete, and big companies have kind of rigged the rules in a lot of ways that insulates them from actually having to face that competition.

I think one of the problems in our … and I think Brendan’s … You’re really right about this whole point you’ve made. I think one of the problems in our politics is that Democrats are nervous about the idea of competition and they’re nervous about business. I think there’s a sort of vaguely held idea that competition is actually the root of the unfairness, and in reality, it’s the centralization of power that’s the root of the unfairness, and that the markets aren’t structured in ways that even the playing field and create opportunity, of course, with an appropriate safety net and regulatory structure and the rest of it. So I think some of it is that Democrats really have an opportunity to rethink how they think about business and the economy, and not just sort of cede a lot of ground to Republicans who’ve really carried a lot of water for big business. |

| Brendan Greeley: | What I want is growth Democrats, and I think that you’re absolutely right that they’re missing language to talk about growth. And then there are very old terms that we used to have that we’ve lost. And in order to use them, we have to reintroduce them and explain them to people. Things like monopsony, single buyer. Right? We have single buyers of labor in some towns, and that produces distortion. It’s a very old term. We just haven’t thought about it in a while, and we need to reintroduce it. Restraint of trade is another one. All that trust law that we got in the late 19th century and the early 20th century, it wasn’t about protecting consumers, it was about protecting other market participants who wanted to trade but were restrained from doing so. But nobody talks about that. You certainly don’t get Republicans talking about that.

There’s a very effective defense against that that large businesses have, which is that they have convinced America that regulation is bad. I think the way we talk about regulation in America is that Republicans say regulation is awful, and it curbs growth. And Democrats try to not say the word regulation. When what of course, we need, a regulation is just a law. There are good regulations, and there are bad regulations. What we really should be having is a conversation about what are the good regulations? The ones that encourage competition. The one that discouraged externalities like carbon. What are the good regulations and what are the bad ones? What are the regulations that say if you want to open a hair salon in a town it’s prohibitively costly for you to get licensed? And there is no political language to make that distinction in America. So let’s take the thing that Chris I know you hold near and dear, which is competition in the telecoms industry. Net neutrality is the smallest concession that you could possibly imagine. Right? Other countries are so far beyond us in terms of requiring that service providers compete. So rather than force them to compete, we’re just asking them for this basic thing where you at least other people to compete over your wires. They say that’s regulation, regulation is bad, ergo we can’t have it. So we don’t have the language to talk about this, and I don’t really know of any Democrats who even know how to have this conversation. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | It’s worth noting too, and I think you’re right about we don’t know how to talk about regulation good versus bad, but it’s also true that anti-trust in some way is really a police function. It’s not a regulatory function. It’s about making sure behavior is appropriate and that the market is structured in a way that facilitates competition. You know in the same way that our banking laws for a lot of the 20th century didn’t have to have a lot of incredibly complex regulatory rules, and so forth, and compliance rules because they were more simple and more structural. And said, “Here, banks need stick to their knitting and there’s going to be some geographic restrictions and so on.” And it seems to me that’s there’s a lot to be gained by thinking about the ways in which policy can structure markets as opposed to minutely regulate them. |

| Brendan Greeley: | Yes, I think you are absolutely right about that. I think that we need to think about why do we have markets? Because they give us growth and prosperity. Why do we have politics? Because they protects us from markets. You know Germans have an understanding of this. Right? This idea of ordoliberalism. In Germany, it’s the idea that the government has to create the market so that the market actors can function properly and productively. We don’t have any sense in America of how it is we create good markets.

And the thing you said about simplicity I think is really crucial. This is the reason why Dodd-Frank frustrates me is that I think the aims of it are very good. I’d rather keep it than let go of it. Right? Given the alternative, I’ll take Dodd-Frank. But one way in which Dodd-Frank could have been much better is if it had just been really simple, but we don’t do simple rules in America. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Well, if we wrote simple rules big companies wouldn’t have any room to evade them, and you know. |

| Brendan Greeley: | Oh, yeah. I mean this is a favorite trick that companies do, which is that they lobby for complex regulations. Their lawyers lick their chops, and then they go to the press and say, “Look how many regulations there are. Look how many pages of complex regulation there is. We need to get rid of it.” |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Aside from your economic research note, what do you recommend that a person read or listen to to learn a little bit about this stuff? |

| Brendan Greeley: | So the Chicago Booth School of Business has done a really amazing site called ProCompetition. I think that’s what it’s called. Luigi Zingales- |

| Stacy Mitchell: | I think it’s actually ProMarket, maybe. |

| Brendan Greeley: | ProMarket, thank you, ProMarket. So Luigi Zingales at Chicago, and this is fascinating that it’s the Chicago school that’s doing this, although it’s a business school and not the economics programs. I think what they’re doing is amazing because they are all hard-headed PhD economists who understand that markets need rules to function, and are going through market by market, and saying this is why this market doesn’t work. And so that to me, is an approach that we need, but again I’m going to say the same thing, I’m waiting for a politician to read that, pick it up and say this is my program. This is the thing that we’re missing in America. That I have not seen yet. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Well, thank you so much, Brendan for coming on. Really enjoyed this conversation. |

| Brendan Greeley: | Thank you, guys. It was great to talk. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Brendan had to run, but I wanted to just note a couple of things that popped into my head over the course of the interview in terms of recommendations. One was that people should both read and watch The Big Short, the Michael Lewis book and movie. I thought it touched on some of the areas that we just talked about. The other is from the beginning of the interview, a book by David Graeber that was pretty popular recently called The History of Debt. The first few pages of that talk about some of the issues that we talked about right at the very beginning.

Did anything occur to you, before we wrap up? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | I’m glad he mentioned the ProMarket site. That’s a really great read, and I’m really glad to see that initiative going, but I’ll just double-down on your suggestion of watching The Big Short. That’s one of my all-time favorite movies in recent years, and it captures so much in such an entertaining and in some ways, moving way. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Yes. I agree.

Well, thank you, Stacy. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Thanks, Chris. This has been fun. |

| Christopher Mitchell: | Thank you for tuning in to this episode of Building Local Power. You can find links to what we discussed today by going to our website, ILSR.org, that’s I-L-S-R dot org. Look around for the Building Local Power show page. While you’re there, you can sign up for one of our newsletters or all of them, and connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

Please help us out by rating this podcast, sharing it with your friends, or maybe hire a local pilot to fly one of those airplanes with the message dangling behind it over a beach. I’m sure that’s really great for carbon dioxide emissions. This show is produced by Lisa Gonzalez and Nick Stumo-Langer. Our theme music is Funk Interlude by Dysfunction_AL. For the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, I’m Chris Mitchell. I hope you’ll join us again in two weeks for the next episode of Building Local Power. Now get out there and do something. Thanks. |

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

If you have show ideas or comments, please email us at info@ilsr.org. Also, join the conversation by talking about #BuildingLocalPower on Twitter and Facebook!

Subscribe: iTunes | Android | RSS

Audio Credit: Funk Interlude by Dysfunction_AL Ft: Fourstones – Scomber (Bonus Track). Copyright 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license.

Photo Credit: Data Center Journal.

Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and, for monthly updates on our work, sign-up for our ILSR general newsletter.