A selection of recent news stories with an ILSR insight into “The Public Good.”

A selection of recent news stories with an ILSR insight into “The Public Good.”

A Thoroughly Modern Way to Fleece the Customer | Protecting Communities From Gentrification | Punishing Corporate Criminals | The Hell With the 6th Amendment | Corporate Parasites

A Thoroughly Modern Way to Fleece the Customer

A Thoroughly Modern Way to Fleece the Customer

In the beginning there were no fixed prices. Every transaction involved a negotiation between buyer and seller. Then, in 1861, as Guardian reporter Tim Adams informs us, Philadelphia retailer John Wanamaker introduced price tags along with the slogan, “If everyone was equal before God, then everyone would be equal before price.” Wanamaker’s stated intent was to establish “new, fair and most agreeable relations between the buyer and the seller.”

For the next 150 years fixed pricing became the norm. Companies determined prices either by pegging them to those of their competitors or by calculating the cost of a good or service and adding a profit, with an occasional white sale or going-out-of-business sale, or discounted day-old bread.

In the 1990s came the Internet and in the 2000s on-line shopping and smart phones. Prices could be changed remotely and frequently. Initially businesses changed their prices largely to take advantage of a shortage of supply (e.g. Uber with its surge pricing) or an increased demand (airlines, in essence, auctioning off tickets to last minute customers).

Big data emerged and with it the ability for businesses to know their customers in a most intimate and detailed fashion. Initially sophisticated algorithms allowed businesses to individualize ads. Now as they’ve gathered even more of our personal data they’ve begun to individualize prices. As Adams notes, the travel site Orbitz calculated that Apple Mac users would pay 20-30 percent more for hotel rooms than users of other brands of computer and adjusted its pricing accordingly. Jerry Useem in the Atlantic maintains the price of Google’s headphones may depend on how budget-conscious our web buying history reveals.

Electronic price tags may soon allow dynamic pricing in brick and mortar stores. Such tags are already in stores in France and Germany and parts of Scandinavia.

The Guardian reports that B&Q, the largest home improvement and garden center retailer in the UK and Ireland, has tested electronic price tags that could change the price of an item, based on which customer is looking at it, something it can derive from the Wi-Fi connection to the customer’s mobile phone. Not yet in stores, but that may be just a matter of time.

Dynamic pricing strives to maximize the seller’s profit by raising the average price he receives. Economists believe that is simply good business tactics. The rest of us remain unconvinced.

We don’t like being taken advantage of. More than half the states have anti-scalping laws, a response to brokers buying up thousands of concert tickets, shrinking supply, and allowing them to charge concert goers far more than the face value of the ticket. Last year Congress got into the act, passing a law that makes it illegal for brokers to use software that bypasses online systems designed to limit the number of tickets an individual can purchase. But these laws target only a small slice of the retail sector and aren’t vigorously enforced.

We’ve also taken action to stop sellers from taking advantage of a scarcity imposed by natural disasters to charge exorbitant prices to desperate customers. Over 30 states have enacted laws against such price gouging.

But as Ramsi Woodcock, Professor of Legal Studies at Georgia State University observes, those outraged by Delta’s reportedly asking $3,200 for a ticket out of Florida as Hurricane Irma approached should be aware that dynamic pricing enabled Delta to charge the same price to last minute customers two weeks before.

We’ve imposed no limits on dynamic pricing, although we’re nibbling around the edges of imposing some constraints on the sale of our personal data. Woodcock believes dynamic pricing could have anti trust implications. Anti-trust is justified by many as a way to stop or break up monopolies that could artificially raise prices and reduce total consumer welfare. In a detailed article, Woodcock argues that big data enables “price discrimination (that) extracts more value from consumers than uniform pricing, by tailoring price to the maximum level tolerated by each consumer.” And thus warrants anti-trust enforcement.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Protecting Communities From Gentrification

Protecting Communities From Gentrification

witnessing an in-migration, often of people with greater means. Rising housing prices spurred land speculation and new developments, threatening existing neighborhoods and reducing the number of affordable housing unit.

Some cities have tried to do right by their long term residents. But the vast majority embraced strategies that in one form or another, bribe developers to set aside a portion of their high rise condos for those with an income below the median. On the whole, this has proven, largely ineffective and unsustainable approach.

In the 1960s some far reaching thinkers and activists developed new concept: a Community Land Trust. The first incorporated land trust was established in 1969. New Communities was a 5,700-acre land trust and farm collective in southwestern Georgia owned and operated by approximately a dozen black farm farmers from 1969 to 1985.

In 1972 Robert Swann, one of the creators of New Communities, published Community Land Trust: A Guide to a New Model of Land Tenure in America. It explained how a land trust differed from conventional ownership. The trust separates the ownership of the land from the ownership of the building. A nonprofit organization, with a board usually composted of representatives from tenants, the surrounding neighborhood and professionals in real estate professions, owns the land and leases it to the homeowner for a designated period, often 99 years. The homeowner has the right to sell the land at any time, but the return to the homeowner is limited.

Keeping the land out of the real estate market holds down housing prices, as does limiting the equity gains that accrue to the homeowner.

In 1984 Burlington, Vermont established the first urban CLT. Burlington offered fertile ground for testing the concept in an urban setting. A rapidly inflating housing market created the need to maintain affordable housing. A new mayor, Bernie Sanders, who was receptive to the concept of social markets afforded the opportunity.

Initially Sanders viewed a land trust with skepticism. “The mayor feared the restrictions on reselling properties would create a form of second-class home ownership,” Jake Blumgart reports in Slate, “If middle- and upper-class people could build wealth off their houses, why should the working class be limited to shared equity? Sanders’ preferred methods of ensuring housing affordability were rent control…and providing direct subsidies to low-income residents who wanted to buy homes.”

But in 1982 Burlington voters rejected rent control in a referendum. And direct subsidies to low income households, to be effective, would have to increase as real estate prices increased, eventually overwhelming the municipal budget.

Bernie eventually embraced the land trust concept as a long term solution to displacement and the loss of affordable housing. In 1984 the city midwifed the creation of the land trust with a $200,000 seed grant and municipal staff support. Later, it made a significant loan from its pension fund to the land trust and raised additional funds from local businesses and federal resources. In 1988, the Burlington Housing Trust Fund was established, bankrolled by a small increase in property taxes.

Municipal sponsorship of a land trust was not universally supported. In his 1996 PhD dissertation, Reinventing Real Estate: The Community Land Trust as a Social Invention in Affordable Housing, James Meehan recalled, “An opposition group upholding property rights organized and picketed the Board of Alderman. One realtor said, ‘If you believe that one of the most precious rights we, as individuals, have in our country, is the right to own land, a right protected by our Constitution, then you should take a long, hard look at this land trust.’”

Advocates prevailed.

In 1984, the same year the Burlington land trust was created, a community in Boston applied the concept on a neighborhood scale. At the time the Dudley Street neighborhood was characterized by burned out and abandoned houses. “(T)he per capita income of the Dudley Square residents was one of the lowest in the nation, on a par with the poorest counties in Mississippi, or Indian Reservations of the West,” noted to Peter Medoff and Holly Sklar note in their book, Streets of Hope: The Fall and Rise of an Urban Neighborhood,

With the support of local foundations, the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI) held a series of meetings. Over many months, hundreds of residents developed a plan that included business development, affordable housing, human service provision, youth development, education, playgrounds and public space. The city adopted the plan, but its implementation required one more innovation.

The “Dudley Triangle” consisted of a tangled web of city-owned land interlaced with tax-delinquent properties, and vacant private lands. The neighborhood pressed the city for the authority to demand that the owners sell the trust the parcels, an authority, called eminent domain, that heretofore had only been exercised by governments. In 1988, the Boston Redevelopment Authority granted that request.

As Harry Smith, DSNI’s director of sustainable economic development told Blumgart, writing for Next City, “we never really used the actual power of eminent domain. We used it more as a stick, so if there were absentee owners who weren’t coming to the table and weren’t engaging we could send them a letter and say we are going to exercise the power of eminent domain. That would get their attention.”

In 1987 the Institute for Community Economics convened the First National Conference. Twenty-four CLTs attended. A year later the number doubled. By 1990 the number attending had reached 120. After plateauing in the 1990s, the number of CLTs again began to grow rapidly, reaching more than 280 today.

Member organizations of the National Community Land Trust Network (which in 2017 merged with Cornerstone Partners to become the Grounded Solutions Network) now host around 25,000 affordable rental units and 13,000-15,000 affordable owner-occupied homes.

Today the 30 acre Dudley Land Trust boasts 225 units of affordable housing, a playground, a mini-orchard and community garden, and greenhouse, as well as commercial space and office space.

The Champlain Housing Trust (CHT), a merger of the Burlington Community Land Trust and the Lake Champlain Housing Development Corporation, which serves three Vermont counties. Today, according to Blumgart, the CHT holds about 565 homes in a land trust plus 2,100 rental and cooperative units. Half are within the city of Burlington. They constitute about 8 percent of the city’s housing stock. In the last two years, CHT has expanded its portfolio by purchasing several hotels and apartment buildings and converted them into housing and lodging for the homeless. Its operating budget is over $10 million.

Some land trusts have expanded to include commercial space. The Anchorage Community Land Trust, founded in 2003, focuses exclusively on commercial development. Vermont’s CHT manages 14 commercial properties in Burlington.

Evaluations have shown that land trusts are viable and effective. They stabilize neighborhoods, keep housing costs affordable, and through the neighborhood’s participation, energizes and revitalizes the community.

The Urban Institute, found that 90 percent of low-income households remained homeowners five years after buying a shared equity, CLT home, far exceeding the 50 percent average home ownership retention rate among conventional market, low-income homeowners, as reported by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Reviewing the resale of 205 housing units in land trusts between l988 and 2008, analysts found that, on average, a Champlain Housing Trust homeowner who resold her home after five and one half years, recovered her $2,300 down payment and earned an additional 412,000 net gain in equity.

The housing collapse in 2008 tested the viability of CLTs. They passed with flying colors. A report by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Outperforming the Market based on data from a 2010 survey of CLTs conducted by the National Community Land Trust Network concluded that homeowners who took out conventional mortgages were over 8 times more likely to be in the process of foreclosure than those with CLT mortgages. That disparity soared to more than 25 times if the homeowner had a subprime mortgage. Similar disparities occurred in the comparative rate at which homeowners were delinquent in their payments.

Comparatively low rates of foreclosure and delinquencies were an inherent result of the structure of the land trust. The non-profit acts as the steward, helping low and middle income residents to buy and stay in homes. In the pre-purchase stage, the non-profit organization protects homeowners from predatory mortgage lenders. After purchase it intervenes where necessary to make mortgage payments current or preclude foreclosure completion via a variety of strategies: financial counseling, direct grants or loans, arranging the sale and purchase of less expensive unit, and working with homeowners and lenders on permanent loan modifications.

For policy makers the Lincoln Institute had an important message, “ CLT home ownership appears more sustainable than private market options for low-income homeowners”

Despite the overwhelming evidence of their success, community land trusts are still on the margins of urban policy, a result of at least four factors.

First, banks continue to be wary of financing units where ownership is divided. Blumgart reports that the North Camden (New Jersey) Community Land Trust collapsed in 2007 because local banks would not allow it to refinance its loans after the Great Recession.

Second, many cities tax CLT property the same as conventional property, despite the fact that its unusual ownership structure gives it a lower market value. Some states have adopted legislation requiring that CLT property be assessed at a lower value than unrestricted property because of its unusual ownership structure. (e.g Florida, North Carolina, Vermont).

Third, new land trusts in a number of cities are confronting rapidly escalating real estate prices that outpace their ability to finance expansion. When the Dudley Street Initiative was born, land in that part of Boston could be had for a song. Now its price is rising rapidly. In 2015, the nascent Chinatown Community Land Trust was thwarted in its first attempt at acquisition when it came short in a bidding war with a developer. (Undaunted, this past March, an a dozen local neighborhood groups formed the Metro Boston Community Land Trust.)

Fourth, cities remain lukewarm, at best, to the concept despite the evidence that the city as well as its low income residents benefit. Foreclosed properties significantly diminish nearby housing values. Depreciation leaves remaining homeowners vulnerable to foreclosure and the neighborhood to increased crime. Foreclosures also impose costs on municipalities. The costs of administrative fees attendant to foreclosure, demolition of vacant properties, declining property taxes can run into the tens of thousands of dollars per house.

One reason cities largely remain on the sidelines is that a significant percentage of their revenue comes from property taxes and they have a self-interest in maximizing the market/assessed value of real estate.

Gentrification has already made deep inroads into cities like New York. According to a recent report by NYU’s Furman Center, only 9 percent of homes on the market in 2014 were affordable to the 51 percent of New Yorkers earning less than $55,000 a year.

Undaunted, in late October, the multi-partner Interboro Community Land Trust was launched, funded with several million dollars from various sources, including from New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. Its units will largely be drawn from within the partners’ existing portfolios. Interboro’s first project will convert 250 units into permanently affordable housing.

While opportunities for land trusts are disappearing rapidly in cities like Seattle and San Francisco, they are still significant in the many cities where in-migration has just begun and gentrification is reserved to only a tiny portion of the city.

Consider that in 2015 Detroit had some 45,000 empty homes. Thousands more face tax foreclosure. In 2015 the Detroit Land Bank was auctioning off more than 20,000 vacant houses.

A coalition of housing activists asked the Detroit Land Bank to transfer some of its properties to a community land trust. After it refused, the newly formed Detroit Community Land Trust Coalition turned to crowdfunding, raising more than $108,000 in 10 days and an additional $30,000 from other funders, enough to purchase 15 houses at tax foreclosure auctions.

Detroit can do much better. Consider what they’ve done for their hockey team. Michigan and Detroit subsidized the construction of a new hockey stadium with $300 million in bonds backed by property tax revenue. The bonds could have financed the purchase for land trusts of about 30,000 homes.

In Buffalo land trust activists are focusing on the Fruit Belt neighborhood around the Buffalo Niagara Medical campus. The expansion of that complex has led to vigorous land speculation and proposed development. Responding to activist pressure in late 2015 the city council imposed a moratorium on the sale of any of the over 200 city owned lots in the Fruit Belt neighborhood until “a duly approved strategic plan” had been created, a plan that must protect Fruit belt residents from “the adverse effect of development.

In Baltimore, which has two small land trusts and some 30,000 vacant homes owned by the city, a coalition has proposed a $40 million investment in CLTs. Mayor Catherine Pugh has endorsed the proposal.

Vermont, with a population about the size of Baltimore’s and some 7 percent the size of NYC remains the pacesetter. In June its legislature enabled the issuance of up to $35 million in revenue bonds dedicated to housing that is permanently affordable.

Punishing Corporate Criminals

Punishing Corporate Criminals

Corporations, like people, commit crimes but unlike people they do not face jail time if caught. The chances their executives will face prison time for their corporation’s malfeasance is vanishingly small.

The penalty for corporate crime is almost always financial. So far the evidence is that financial penalties have not effectively deterred corporate misconduct is manifest.

As I’ve written before, a New York Times analysis of enforcement actions during 1995-2010 found at least 51 cases in which 19 Wall Street firms had broken antifraud laws they had agreed never to breach. Forbes reports that Pfizer paid $152 million in 2008; $49 million a few months later; a record-setting $2.3 billion in 2009 and $14.5 million in 2010. Each time it legally promised to adhere to federal law in the future. Each time it broke that promise.

A recent comprehensive study concludes, “(t)he evidence fails to show a consistent deterrent effect of punitive sanctions…”

The sad truth is that corporate crime pays. In 2006, Morgan Stanley entered into a complex swap agreement with the New York electricity provider KeySpan that enabled the two companies to push up the price of electricity. The Times reported the total cost to New Yorkers of this collusion came to $300 million. Morgan Stanley was paid $21.6 million for handling the swap agreement. The financial penalty imposed on Morgan Stanley came to $4.8 million.

Could a financial penalty ever effectively deter corporate crime? In theory, yes, but only if there were a high degree of certainty the crime would be detected and the penalty would truly severe.

But the federal government has too few resources, and even in the best of times, insufficient motivation, to successful prosecute corporate criminals. Thus the financial settlements. Adding insult to injury, enforcement authorities often fail to even collect fines they’ve imposed. As Benjamin van Rooij and Adam Fine, of the University of California Irvine have noted, collection rates have been well below 50 percent across different enforcement agencies, with the Department of Justice collecting only 4 percent of the penalties imposed.

Not surprisingly, the Trump Administration is proving far more lenient to corporate offenders. In its first six months, the Wall Street Journal reports, “[p]enalties levied against firms and individuals by the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority…were down nearly two-thirds compared with the first half of 2016.”

One might inquire, isn’t a multi-billion dollar fine a deterrent? Not for global corporations, for whom it is simply an unwelcome inconvenience, a cost of doing business, like bribing officials in other countries. Purdue Economics Professors John M. Connor and C. Gustav Helmers examined the market impact of over 280 private international cartels from 1990 to 2005 and the fines imposed on them by various governments. They estimated these criminal conspiracies in restraint of trade raised prices by $260-$550 billion. The median overcharge was about 25 percent of affected commerce.

A fine of about 25 percent of revenue would repay the financial damage done. But that’s assuming wrongdoing is caught every time. The Economist suggests that catching one in three violations would constitute a good track record for regulators. That would translate into a fine of 75 percent of revenue simply to compensate for the total global damage and it would be even higher if punitive damages were imposed. The study found actual fines ranged between 1.4 percent and 4.9 percent.

In the waning days of the Obama Administration, the federal government took steps to impose a much higher penalty on serial corporate offenders, threatening them with the potential loss of billions of dollars in government contracts.

In doing so they relied on a 2013 report by Democrats on the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee that found “58 of the 200 largest penalties for violations of the health and safety standards, or the largest back pay awards, were assessed against large government contractors …”

“Forty-nine (of these) federal contractors amassed a startling 1,776 separate enforcement actions in six years,” the report continued. “These 49 companies, which received $81 billion in federal contracts in fiscal year 2012 alone, were assessed a total of $196 million in penalties for neglecting to pay workers earned wages or failing to uphold safe working conditions.”

In 2014, Obama issued an Executive Order requiring government contractors to report violations covering 14 workplace protections, although in typically liberal haste-adverse fashion the Order was only implemented on October 1, 2016. Four months later Trump countermanded the Order.

If the federal government will not step in to hold corporations responsible, states and localities must do so. The hundreds of billions of dollars states and localities spend collectively on contracts could prove a potent weapon to combat corporate criminality.

If states and localities do step up to the plate they will be immeasurably benefited by the years of painstaking data gathering done by the Corporate Research Project, an affiliate of Good Jobs First. Several years ago the Project launched the Violation Tracker, the first easily searchable database on corporate misconduct. This includes violations of consumer protection, environmental, wage and labor, health and safety laws. It covers price fixing and bribery and cases brought by 43 federal regulatory agencies and the Justice Department. This September Project staff nearly doubled the size of the database to 300,000 entries detailing more than $394 billion in fines and settlements going back to 2000.

Photo Credit: Good Jobs First.

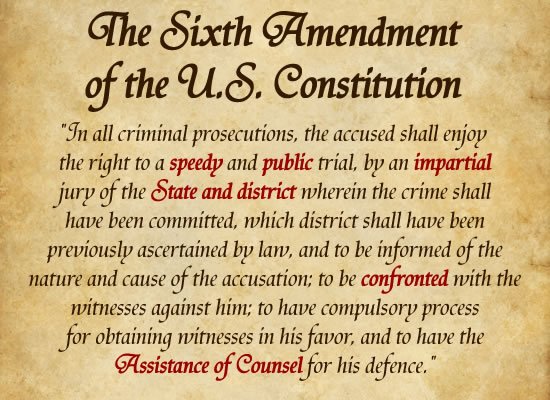

The Hell With the 6th Amendment

The Hell With the 6th Amendment

In 1963, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a right to an attorney is Constitutionally mandated by the 6th Amendment. Writing for a unanimous court, Justice Hugo Black declared, any person “who is too poor to hire a lawyer cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him.” “Lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries,” he announced. The Court ordered every state to provide lawyer for accused felons. Over the following years the right was extended to anybody facing the possibility of detention.

Anyone familiar with cop shows knows one outcome of the 1963 decision. Miranda warning that advises those apprehended, “You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you.”

States have rarely, if ever, willingly financially supported the rights of poor people of color to an adequate defense. In the decades following the Court decision, after the country began arresting and incarcerating people at a rate unprecedented in any nation with an independent judiciary, public defender budgets stagnated even while the number of cases they had to handle soared.

As John Oliver explained in a recent typically hard hitting commentary, 60 to 90 percent of criminal defendants need publicly funded attorneys, depending on the jurisdiction. The system is collapsing under its growing caseload. Today in Fresno, California each public defender annually must represent a staggering 1000 clients. State guidelines recommend a maximum caseload of 150.

The lack of public defenders results in some detainees end up staying in jail waiting for attorneys for longer than the potential sentences for the crimes of which they were accused.

The backload of cases sometimes only allows public defenders minutes on each case. One result is that 90-95 percent of criminal defendants “cop a plea”, pleading guilty in return for a reduced sentence even they are innocent.

In Louisiana, the Guardian reports, the backlog has become so bad that in the 16th judicial district, up to 50 poor defendants are convicted and sentenced all at once, for major felonies while the single public defender representing all of them struggles to present any of the fact sand arguments in their separate cases.

In an attempt to make ends meet, the beleaguered public defender office in New Orleans resorted to a crowd funding appeal. Thanks to its appeal being publicized by John Oliver, it met its $50,000 goal.

A 2013 report by the National Juvenile Defenders Council cited by the lawsuit found that 60 percent of state’s young defendants come before its courts without legal counsel. Since 2014 Missouri’s public defender program has lost 30 staff members to funding cuts yet their case load has increased by 12 percent to more than 82,000 cases a year.

A frustrated and angry Michael Barrett, director o f the Missouri Public Defender Office tells the Intercept, “poor persons in this state, including poor children, are being pushed through the criminal justice system, fined excessively, and deprived of their liberty.”

Public defenders in Missouri are funded entirely by the state. After Barrett delivered a well-documented report on the dismal, unconstitutional situation the state legislature appropriated an additional $3.47 million. In the Atlantic, Dylan Walsh describes what came next,

“Persuaded by the case, Missouri’s General Assembly approved a $3.47 million funding increase for Barrett’s office. But Governor Jay Nixon vetoed the legislation when it arrived on his desk. When the legislature overrode his veto, Nixon used executive authority to simply withhold the money. The next fiscal year, he reduced the budget of the public defender’s office by—exactly—$3.47 million. Then he signed off on $4 million in State Fairground improvements, $52 million for a new state park, and $998 million for a new football stadium.”

In Missouri the public defender office can draft attorneys if needed. In 2016 Barrett exercised that authority to compel Nixon to represent a 50-year old indigent white man. “Given the extraordinary circumstances that compel me to entertain any and all avenues for relief, “ he explained to the citizens of Missouri,” it strikes me that I should begin with the one attorney in the state who not only created this problem, but is in a unique position to address it.” Within days a state court ruled he lacked the authority to draft a sitting Governor.

Some states have systems that willfully or not, encourage defenders not to represent their clients best interests. Utah’s public defenders are entirely funded at the county level. All but 2 counties contract with outside attorneys who are paid a fixed fee per case. That gives them a perverse financial incentive to minimize the time they spent on each case.

Louisiana uniquely funds the majority of indigent defense costs through fines and court fees. Local revenues constitute almost 70 percent of the system’s budget, the bulk generated from traffic tickets. Anyone found guilty is assessed an additional court fee. Defendants who can’t pay the fees, which can be more than $350, can be jailed for contempt of court. Dylan Walsh writes, “for public defenders, reliance on these court fees places them in the questionable position of drawing a salary from the guilt of those they represent; defendants who are found innocent pay no court costs.”

The catastrophic nature of the public defender system has generated numerous lawsuits. The ACLU has sued the city of New Orleans and the state of Louisiana for “indefinite denial of counsel”, along with the states of California, Michigan, Montana, Idaho, Washington and Missouri.

Some suits have borne fruit. A legal challenge by the ACLU in Idaho ultimately led the state to increase aid to its counties’ public defender offices by $5.4 million.

A lawsuit against the state of New York filed in 2007 ultimately resulted in the state legislature agreeing to pay 100 percent of public defender office’s expenses through 2023, a cost estimated at $460-480 million. Governor Andrew Cuomo vetoed the bill. The legislature revised it to halve the state payment to $250 million to the counties. Cuomo signed the revised bill in April 2017.

Jennifer Early, Professor of Sociology at the University of Arizona proposes another source of funds that would generate a more positive feedback loop: civil forfeitures. Police have the right to seize property they believe was involved in a crime, even if they don’t actually charge the owner of the property with a crime! The proceeds from these seizures, which nationally run into the billions of dollars a year, largely go to local law enforcement bodies. Not surprisingly, this has led law enforcement bodies to be more than zealous in seizing private property. Public outrage has convinced some states to shift the revenues to the general budget. Professor Early argues that these funds should be used, at least in part, to support public defenders. This would curb the perverse incentive the police now have to expand seizures while funding attorneys who can keep their actions in check.

I hope Ms. Early’s proposal gains traction.

Corporate Parasites

Corporate Parasites

In the 1980s, leveraged buyouts became financial engineering’s newest invention. Corporate raiders would use the assets of the target corporation to collateralize the debt required to take it over. The resulting large debt payments burdened the target business. Some went bankrupt. But Wall Street firms made a handsome profit by extracting hundreds of millions of dollars in cash from the business in management and other fees.

Leveraged buyouts have been rebranded as private equity investments. The name has changed. The cannibalization of corporations is the same —

Pam and Russ Martens report that since January 2015, 43 large retail or supermarket companies have filed for bankruptcy. Private equity firms owned eighteen or 40 percent of them. Meanwhile, according to Nabila Ahmed and Sridhar Natarajan in Bloomberg Markets, since 2013 private equity firms have extracted more than $90 billion in debt-funded payouts. Since 2012, these firms have generated 14 percent annualized returns after fees, double the 7.4 percent returns on high yield bonds in about the same period.

In late September the 69-year old retailer, Toys R Us filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, the second largest US retail bankruptcy ever. Wolf Richter notes that at the end of fiscal year 2004, the last full year before its private equity buyout, Toys R US had $2.2 billion in cash, cash equivalents and short term investments, By the first quarter of 2017 that had shrunk to just $301 million. Over the same period, long-term debt surged from $2.3 billion to $5.2 billion.

Richter observes that over the same period the annual revenues of Toys R Us remained essentially flat at just over $11 billion. Since 2013 overall toy sales have been growing by a compound annual rate of 5 percent. Toys R Us certainly faced significant challenges from companies like Amazon and a changed retail environment. But it might well have had the flexibility to adjust to changing market conditions without the burden of hundreds of millions of dollars in debt payments that put it at a competitive disadvantage to less highly leveraged competitors. (Instructively, smaller, independent toy stores never attracted corporate raiders, continue to cater to their customers, not Wall Street, are not burdened by massive debts and are doing fine.)

In October 2012 Payless experienced a leveraged buyout that increased its debt from about $125 million to about $400 million. Within two years the Martens write sponsors siphoned over $400 million out of the company. In 2017, Payless declared bankruptcy.

Early in 2017, 102 year-old discount retailer Gordmans Stores filed for bankruptcy less than 4 years after Sun Capital borrowed money to pay itself a special dividend.

In 2008, four years after, private equity firms bought Mervyn’s from Target Corporation the chain was forced to shut its 175 locations and shed 18,000 jobs. Its workers and suppliers and dozens of small to towns on the West Coast suffered grievously. The private equity firms did not. They paid themselves $200 million in special dividends from borrowed money. Mervin Morris, 96, who founded the chain in 1949 sadly recalled, the stores “couldn’t sustain the additional debt they put on.” “They were after the dollars and evidently came out well,” he observed and added, “They broke my heart.”

Eileen Applebaum and Rosemary Batt, authors of the landmark book Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street describe the way one private equity firm cannibalized the ice cream chain Friendly’s. As Bob Kuttner summarizes in a 2014 review of their book, “First it loaded the company with debt, then paid itself special dividends, then laid off workers, and ultimately took Friendly’s into bankruptcy. But then ‘a second Sun Capital affiliate announced its intention to acquire the restaurant chain. A third Sun Capital unit came forward to provide a loan to finance the chain’s operations while it was in bankruptcy.’ Such maneuvers enabled Sun to strip assets from the operating company and shed debts including pension obligations—yet retain control.”

Even a leveraged buyout many would consider successful in that a failing firm survived, when the cost-benefit analysis goes deeper, may be viewed with considerable skepticism.

Wilbur Ross, who after a stint as a bankruptcy specialist at Rothschild Inc. set up his own private equity firm, WL Ross & Co acquired several bankrupt steel companies in 2002 and 2003, paying $90 million in cash and assuming $235 million in debt. One condition of the purchases was that health coverage for retirees would be eliminated and pension liabilities shifted to the federal Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation where workers would receive substantially lower benefits. When Ross cashed out in 2005, Appelbaum and Batt note, “his three year investment netted him $4.5 billion—just equal to what retirees lost in their health and pension plans.”

Wilbur Ross is now Secretary of Commerce.

Sign-up for our monthly Public Good Newsletter and follow ILSR on Twitter and Facebook.