Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

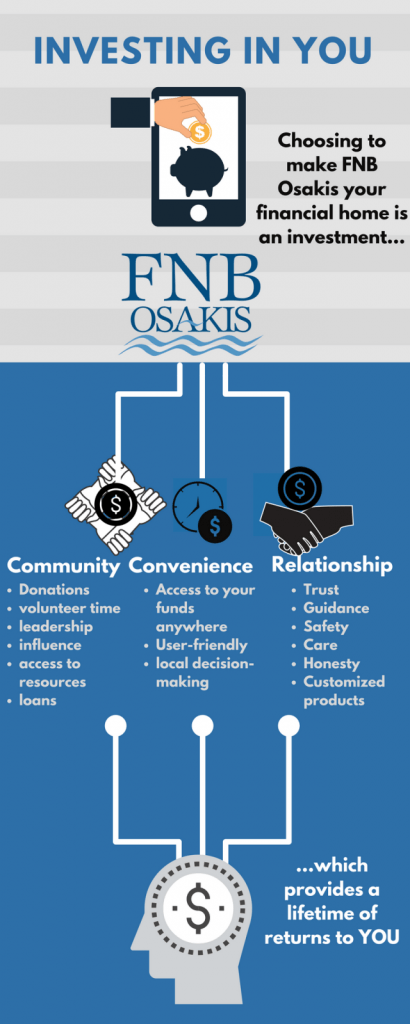

Welcome to episode sixteen of the Building Local Power podcast.In this episode, Christopher Mitchell, the director of ILSR’s Community Broadband Networks initiative and Stacy Mitchell, the co-director of ILSR and director of ILSR’s Community-Scaled Economies initiative interview Building Local Power’s first guest outside of ILSR. Our guest this week is Justin Dahlheimer, the President of the First National Bank of Osakis in west-central Minnesota. The trio discuss the benefits of community banking and how banks that have a vested stake in their community lend in ways that increase the vitality of communities like Osakis.

“We’ve got a stake in every customer’s personal financial livelihood. It should be that way. It’s embedded transparency. It’s accountability,” says Justin Dahlheimer of the relationship community banks have with the people that they serve. “We want to weather the community risk and be able to charge off loans, not come back after customers and ruin financial lives and move on to the next thing… [We want to] work together and leverage dollars to bring more wealth into the community versus just recirculating or poaching wealth from other banks. We want to create that wealth.”

Get caught up with the latest in our community banking work by exploring the resources below:

From our guest, Justin Dahlheimer:

From Chris Mitchell:

| Chris Mitchell: | Hey, Stacy, what’s happening with community banks around the country? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Well, in 2010 the U.S. was home to about 7,000 small locally owned banks. Today we’re home to about 5,000, so a pretty dramatic drop in just 7 years. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Yeah. I would assume that we haven’t lost a lot of need for local banks. Today we brought in the president of First National Bank of Osakis, Justin Dahlheimer. Welcome to the show. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Well, thanks for having me on. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Stacy, do you remember this voice? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | I do. Justin used to work for us. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Right. Founder David Morris said that if we were going to have you on the show we had to remind people that you did the mapping that really put our North Dakota pharmacy map over the top, and actually is back in the news again. The report that showed that North Dakota’s local pharmacy law really has led to superior coverage and access for people in North Dakota. Welcome back. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Thanks. I have been kind of keeping abreast to that issue and all the things that we did look at here. I tune in every time I see the North Dakota pharmacy law come under fire, and I’m always pleased to see your guys’ research. It seems to never die. It’s a good thing for pharmacies, and I was really proud of the work I did here and really proud of the relationships I made. Glad to be back. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Well, we’re thrilled to have you back. For people who have listened to Building Local Power before, you probably recognize Stacy Mitchell, the person who runs our independent business work. I’m Chris Mitchell, the guy who does a lot of the broadband work around here. Actually, I should say I run the broadband program. I take credit for all the work and I don’t do most of it.

I think we wanted to talk about what’s happening with local banks. Justin, I wonder if you could just start by talking about what a local bank is. You had noted when we talked previously that you have a lot of experiences and have a real good sense of what’s happening but some of the stuff we’re talking about might be more specific to more rural or non-metro community banks. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Yes, and that’s exactly where I come from. We’re a small community northwest of the Twin Cities about 120 miles in a population about 1,700 people. A local bank is very much the livelihood of that community. We’ve been around since 1903. That’s a lot of economic cycles that you rely on financial institutions to keep everything steady and to keep these small communities on the map and to keep reinvesting dollars into them. That is what we believe community banks should be in the independent community banking world and why we feel very passionate about the range of products and the range of roles that we have to play. I think there’s a stark difference between the ways a lot of these rural community banks are operating for their communities and the way banks and financial institutions are operating in the urban environments. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Clearly the context that you’re operating in is a bit different from a city, but it’s also true that urban areas have a lot of great community banks and credit unions. It’s a different environment but equally vital in those neighborhoods, wouldn’t you say? |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Yes, I would agree. We like to look at our role as community bankers and the amount of hats that we wear and organizations we touch on a daily basis. The same happens in these urban areas and the ideal of knowing our customers and having a long vested relationship with them and the stake of their business or them as just their families. Where they’re headed on their financial journey matters whether that’s in a city, small or big, and they can equally play a large role. I just feel management’s relationship to their customers in the locality is very important. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Yeah. I think one of the reasons I just brought up that dichotomy was to get a sense of, I think, there’s a continuum of banking. On one side are the giant fee-driven banks that, I think, crushed our economy 10 years ago. On the other end are very small local community banks. I just wanted to make sure that our listeners know that although Justin has experience with all kinds of local banks, I think we’ll be talking about your perspective largely coming from one of a smaller community bank. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Before we got together to do this episode, I went to the FDIC’s website and I pulled up the balance sheet for your bank, basically your financial … Where are all your bank’s money is going and what it’s going to be used for. I did the same for Bank of America, which of course one of the largest banks in the country. I think they have about $2 trillion in assets and they’re enormous. What’s really striking is I think a lot of people think that local banks are just smaller versions of big banks, but when you look at the numbers it’s two completely different businesses. The one that really jumped off the page to me is when you look at Bank of America, they have just 2% of their assets going to small business and farm loans. When I look at First National Bank of Osakis, it’s 23% of your loans going to small businesses and farms. That’s a really dramatic difference. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about your role in the local economy and why that difference is so stark. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | On the micro level that we … In our balance sheet it looks at loan volume and loan size. That’s really what it comes down to is loans are costly to put on. When you’re a large bank like Bank of America and you’re in a volume-driven world, you’re going to gravitate towards those larger loans because the costs advantages, the ability to offer a lower rate, and just in general the overhead is lower.

For small community banks that are doing small loans like we are; under $100,000 for the most part, even under $50,000 on mortgages, the time invested in those relationships it’s not cost effective for Bank of America to build a business model on that and provide value to its shareholders, whereas for us it’s a necessity. We have to do those loans. It’s vital for our community and our market share. We’re going to spend our time doing those things and spend our relationships with very small loans versus you could talk to a Bank of America customer who probably has a line of credit unsecured that’s $75,000 to $100,000. I would say I put on more mortgages for $75,000 to $100,000 in the last 3 months than I would ever put on unsecured. My board would be a little concerned if I was putting on unsecured loans for $75,000 to $100,000 with the customer base that we have. It’s at that level you’re building those businesses and keeping them in your communities, and that’s where we have to be. On the other side there’s the rate difference. When you try to have a discussion and negotiation, Bank of America stated rates in the Wall Street Journal are going to be a lot lower because they’re dealing with large loan customers, large companies. We’re dealing with small customers, smaller scale relationships, and we’ll have a little bit higher rate. On a nominal level it’s obviously much less in interest they’re paying. It becomes that discussion to the general public, why are small community banks charging a higher rate. Well, the scale is a very misleading factor and it becomes too simple, I guess, to report the rates for each institution and not consider the fact that there’s a lot of costs that goes into these relationships. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Well, one of the things that I’m always interested in is this idea of a fee-driven bank. I wonder if you can just talk a little bit about the difference in business model between a bank like yours and what we think of as a fee-driven bank like a Wells Fargo or Bank of America. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Yeah. I think the best way to sum that up is banking in a sense has become a commodity-driven industry. The mortgage and products we offer … They want that marketing scheme to make it look as a transactional relationship. You’re going to go out to get a mortgage like you’re going to go out to get a loaf of bread. Everybody’s going to compare their costs, and you’re going to buy the cheapest one.

Well, going back to the financial meltdown and the mortgage crisis, a lot of people assumed that every mortgage was the same. Well, it’s not the same and that’s why Dodd-Frank came [in vogue 00:08:27] and that’s why a lot of the regulation came was to weed out what different mortgages really cost. When you’re in the business of making a lot of loans and keeping rates low, you’re going to have to make money somewhere, and it’s going to be on the fee side and that’s where the large banks lived. It was putting fees into their contracts, into their mortgages, into their lending relationships, deposit relationships to pay for the overhead to do these types of loans versus a bank that has a long lasting relationship with a customer that has a deposit account that has been there since they were a child. The products become a relationship based where you’re going to price into that relationship more on the rate side because it’s an ongoing relationship versus the large banks, which are trying to securitize these mortgages and sell them off the investors. They’re not holding them locally on their balance sheets and to do that they’ve got to get to the lowest cost point but they’ve got to make money to keep in the doors. The more they can do, the more money they can make, and they’re going to do that on the fee side. I actually was curious on this topic. The way I look at it as a banker is on my gross income for the year; how much is coming, what percentage is coming from non-interest income, which is fees, and what percentage is coming from interest income. I tend to look at things in our industry as small maybe being $1 billion versus the legislation says a $10 billion bank is a small bank. I would say under $1 billion. Banks under $1 billion, as a percentage of total income have 16.5%. Banks over $1 billion are at 21%, 5-6% more of their income is coming from fees. We’re charging less fees but a marginally higher interest rate. We feel that is a better way to price a relationship. We’re saving them money on the cost side. |

| Chris Mitchell: | I know Stacy wanted to jump in but I also wanted to say I’m willing to bet that you have not lost any of your customers’ paperwork and foreclosed on them because of your mistakes. Stacy, what did you want to add? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | There was something that really struck me about what you just said, Justin, which is the different motivations for big banks versus local banks. Essentially if the big banks have this fee model, they want to make money on the fees and the churn and so every mortgage they do they get fees, every mortgage they securitize they get fees, and then they sell it off and they have nothing else to do with it. Every loan and so on, they just want to collect those fees. They want to open checking accounts. They charge higher fees typically on checking accounts.

When you talk about your bank, what you’re saying is we want to make money on the interest, meaning that we want to have customers who are able to pay back their loans. We’re going to have a long term relationship with them because over time as they pay back those loans we’re going to make money on the interest. It’s really striking because that essentially means that your bank can’t be profitable and do well unless your customers are doing well. Whereas a big bank, and we saw this spectacularly in the financial crisis, they can collect all those fees and blow up the economy and their customers can lose their homes and have every bad thing happen to them financially and the banks are still fine because they’re not tied to those customers anymore. Whereas you have this very connected relationship to your customers’ well-being. I imagine, especially being in a small community, if the town is doing well you’re doing well, and if the town is doing badly you’re doing badly. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Exactly. We’ve got a stake in every customer’s personal financial livelihood. It should be that way. It’s embedded transparency. It’s accountability. Like you said, Stacy, the bank’s doing well when the community’s doing well and vice versus. It’s a duty, I think, as a local financial institution to be forward looking enough to price into your business model the fact that we do have economic cycles. We want to weather the community risk and be able to charge off loans, not come back after customers and ruin financial lives and move on to the next thing that the community needs to happen and have those ongoing relationships with community leaders to motivate local resources to do good things for the community and work together and leverage dollars to bring more wealth into the community versus just recirculating or poaching wealth from other banks. We want to create that wealth.

I think that comes from having a stake in the game. I think that’s why the interest margin and that profit focus has always been a much more trustworthy relationship but large marketing and misleading fees and what you can control of what the customer sees can make that … Big banks say we just charge lower rates. It’s compelling but it’s on us as a small financial institution, a small community bank to change that discussion by educating our customer base and marketing based on education and put a real focus on financial literacy. I think that is where our industry is really failing. That’s an opportunity for us to really get into schools, get into households, and educate because it’s not being done properly. |

| Chris Mitchell: | I asked my wife, who worked for a local bank out of Walker and one of the regional … It had 5 branches and she worked for one of the branch banks about her experiences. Her eyes almost lit up talking about the manager who she said just did everything she could for the community. She said something that I just thought was amazing, I’d never considered before and that’s that they made these loans of $100, $200 to people to help them to build up credit so that they could get experience borrowing and the bank would have an experience knowing that they would pay them off. I’m willing to bet that Bank of America has zero loans for $100. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | It’s all credit card based in the big companies. They’ll give you a credit card and some would say with a pulse and now it’s up to you to sink or swim, rather than structuring transactions with cash flows, doing the prudent underwriting at a micro level that they feel is not worth their time because of the cost effectiveness of it versus a community bank which has a duty as a financial educator to do these sorts of things and to build strong financial wherewithal. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | I guess going back to the statistic that I mentioned at the start of the episode about the decline in the number of community banks, a lot of them are being bought up or merged into bigger banks. I’m curious, Justin, about what the pressures are there for local banks to do that and what your sense of why we’re losing so many local banks despite how important they are to communities, to local economies, and to job creation. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | I dwell on this often because I’m periodically in a room full of bankers, and the first thing that they complain about is regulation. It’s important to understand that the Dodd-Frank laws, while I believe a lot of that regulation was necessary, the scale of that regulation was to include banks that very much are living with the accountability I just discussed. We live with our business relationships on our sleeves, so the added regulation of showing our work is almost blasphemy to this group of banking and bankers that have been around for hundreds of years in family generational banks or independent banks. They lose the optimism. We have to go through regulatory exams. We’ve always had too. Now they’re adding layers of regulation and another regulatory body, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which I do feel does good work and they’re in the right areas but sometimes they creep into areas and include small banks into things that they doing need to be doing.

A good example is the Civil Service Member Relief Act, where we have to pull a report on any consumer customer to verify they’re not in the active military. I could have somebody I went to high school, somebody I know very well, maybe my next door neighbor come in and if I don’t pull a report verifying that I looked that he’s not an active military member, I will be written up and could face a violation. That is ridiculous, in my opinion. Should it be done in certain communities, in certain localities, and with certain scale of banks and did they abuse it? I bet they did, but for us it’s tiring and when you add more and more regulation like that that includes us small independent banks that we’re very much not the problem, board rooms get exhausted, strategies get co-opted, and they feel the pressure to sell because they just don’t feel the liability and the profits that are being siphoned off for regulation is worth it. A good example of how much regulatory cost is I’ve seen surveys out there that say banks are facing 5 to 8% more in regulatory costs. Our bank alone, I did this math off our budget last year, 20% more of our net income I think is gone due to increased regulation. That’s a large figure to explain to a board. Then we have to make up for that in other areas and trying to get into niche lending, which I think you’re confining yourself to more of a type of loan that makes you more susceptible to economic turns and even more so you get into the fact that a lot of our products are being co-opted out of us so we’re less diversified in our portfolios than we’ve ever been because the regulation is forcing those products to bigger banks that have more economies of scale. |

| Chris Mitchell: | It seems like the other half of the equation is that it’s harder than ever to create a new local bank and community bank. Stacy, you probably have a statistic on this in terms of how many new banks there are. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | I think we’ve only had one new bank approved in the last 5 or 6 years and that’s it. It’s a striking change because before that we would see banks close every year, a local bank, or merge into bigger banks but we would also see lots of new banks started. That made up for a certain amount of the losses. After the financial crisis, regulators just essentially stopped approving new banks. I think the low interest rate environment has also made it less attractive or harder to start a local bank than it used to be, but there’s clearly something going on with regulators not allowing new banks to form as well. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Exactly. You’re seeing less all-inclusive local community banks the way I described my bank than you would see from a new bank perspective. They’re going to be more targeted in industries and niches that serve a common purpose. For example, financial tech companies looking for banking charters eventually because they have great software products that make a certain type of banking more convenient. That’s probably where you’ll see more new charters in the future, and it’s not going to be doing community style banking where they’re rolling up their sleeves and doing the necessary things from a short term and long term perspective for the community and for the consumers that they do business with. |

| Chris Mitchell: | One of the reasons that we invited you to the show actually comes from you commented on our Facebook page. This is about that tension between credit unions and banks. I think someone was basically saying everyone should go to a credit union and you responded that you need to recognize that local banks are incredibly important and that credit unions are part of the ecosystem but shouldn’t be the only option. Can you talk a little bit about that tension between the banks, particularly smaller banks, and credit unions? |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Credit unions have morphed into a world that looks a lot like the large bank, the Wall Street bank that we as independent community bankers don’t like. Even worse, they don’t have to pay taxes the way we do. They have a lot of money to divert into lobbying to expand their market areas and to expand their customer base in ways that weren’t originally intended. It’s another moving part that we’re competing against that isn’t dealing with the same factors but yet they have the perception that they’re populists on those large credit union waves, that they’re for the people, that they’re owned by the people. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Right. If I could just break in for a second, if I’m understanding correctly, there’s some credit unions, I think, that are getting very big and aggressive but not all credit unions necessarily. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Exactly. I think most bankers would say as originally intended, those credit unions dealing with common affiliations, unions, trade associations, even the military, they do great things. They’re dealing with under banked folks and they’re leveraging community dollars in those types of communities to help do great things. Those are great credit unions.

The ones that are operating like large banks are the ones that are giving credit unions a bad name and are the ones that are really causing the local community banks, which in my opinion my community bank operates a lot like the way credit union is intended. Everybody who’s a customer of my bank is somebody from my local community. They have a common affiliation. We’re in a lot of ways like the original credit unions were intended, but as we get nameless and faceless and we get more profit motivated and more scheme motivated the legislation has allowed the large credit unions into areas like commercial lending where they don’t have, number one, the expertise and, number two, the jurisdiction. They’re not intended to be there. They’re only there because it drives more profit for them to in some ways give back to their members but now their members are probably more vague than you and I. We have more in common than probably a lot of the credit union members in the large credit unions. That is the issue that drives us. We started things with a fee-based motivation or an interest or long term relationship based, those statistics that I cited on percentage of gross income coming from non-interest income, credit unions beat banks far and ahead. The large credit unions have 30% of their gross income coming from fees. My small bank that I work for is 3.5% of our gross income comes from fees. That’s a commodity-based relationship. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | It’s really interesting what you just said because it speaks to something that comes up all the time in our work here at ILSR, which is that scale really matters. When you’re talking about these giant credit unions that now span multiple states or in some cases even are national, ostensibly they’re customer owned but at that scale they’re not really … It’s not really a democratic institution. They’re not connected to place and community. They don’t have the kinds of relationships that a local financial institution has. In the same way we’re talking about the difference between a local bank versus a big bank, it’s the same idea with credit unions and just because they have this different, in theory, this different ownership structure doesn’t necessarily make them any different because that scale is so huge and they are disconnected from place. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | I think geography really matters on how legislation is crafted and how regulation applies. The closer geography you have to your customer base, the more accountable you are, and I think that credit unions, banks, all of the above should operate under that mantra. As the general industry gets independent community bankers angry is the fact that we’re painted with the brush of a financial crisis that we very much have nothing to do with. Whether I know the causes of that financial crisis or not, I know it came from the fact that they allow the bigger to get bigger without a lot of control and yet the lobbying includes the smaller into those legislative discussions because they know they have economies of scale. If they’re going to get more regulation, we’re going to get more regulation, and it’s going to hurt us disproportionately more. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Yeah. It’s really interesting this point about geography and also I’m thinking back to what you said about the regulations that you’re entangled with and how difficult that makes it to operate now. Its striking, back from the ’20s and ’30s all the way until the big changes in banking law in the 1990s, we used to have these laws in place that said you have to stick close to your community. You can’t just spread all across the country. You have to have a geographic focus to what you’re doing and really be rooted in place. We limited the ability of banks to grow big by just spanning the country.

We also limited the ability of banks to mingle different kinds of businesses, so if you were a commercial bank with FDIC insurance, that is the government taxpayers were protecting your deposits, you couldn’t engage in like Wall Street gambling. You couldn’t do all of the securities trading that you see big banks doing now. We had this strict separation, so if you want to be an investment bank and do Wall Street stuff, great but you’re not going to have an insured deposits. If you want to be a commercial bank, then you can’t be messing in that kind of stuff. Those two policies really kept banks much more regional or local in their focus, much safer over the long term, but the other great thing about that structural approach is that we then didn’t have to write all these nitty gritty rules governing every little bit behavior because we just kept created the right kind of structure to align banks with their communities. Obviously we had some consumer protections. We need those kinds of things, but we didn’t have to have just this crazy mass of rules because we weren’t trying to govern these really institutions in the case of Bank of America, Wells Fargo that have become so big and complicated that they’re really ungovernable. It seems to me when we talk about regulation that part of the problem is it’s not more or less regulation, it’s smart regulation is the issue. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | I think it’s more a human focus on a banking a relationship. I will go back to that periodically but that is really what we’re doing now to combat our larger competition is we’re breaking down that wall of what a banker is. It’s not that mean person who caused the financial crisis. It’s that person that is involved in city council, a firefighter, a coach that you know, somebody you can trust. |

| Chris Mitchell: | To be clear, I think you’re most of those things but if you’re also a firefighter I’m very impressed. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | I am. Yeah, volunteer firefighter. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Oh, wow. You’re all of those things. That’s very impressive. You’ve been busier than I have since you left. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Small community, got to wear many hat. That’s something that we should publicize as a banking community because I know a lot of community bankers who do just as many interesting things. If we can get into kids’ minds that that matters and that’s more trustworthy because you know more about that person, it’ll pay long term dividends, and that’s what we’re in the business for, being there in 10 to 20 plus years to see the rewards and them doing well financially so our community is. |

| Chris Mitchell: | You said you wanted to end with a message of hope. I actually wanted to prompt perhaps a different message of hope and then you can sure your other one but that is you came from a county that voted heavily for Trump. In describing it, you’re someone everyone knows you’re not a Trump supporter, that you’re not a Republican but it sounds like you bring a message that rural America still gets along even among different political perspectives. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | I think geography matters, Chris. I think when it comes down to discretion, no matter what you are; blue, red, or purple, being able to have a stake in the decisions that matter in your community matter to just everybody who lives there. We can unite on that and on that level make change happen that is good for the community. That’s what we focus on and that’s what I’ve focused on in our community. We want to bring people together and realize that we may not line up on all these other issues that the national media wants us to that galvanized the social issues but living next to one another has always mattered a lot and will continue to, and we’ll continue to fight for that.

The other hopeful message is I just feel community banks, in general, have a nice opportunity to drive financial literacy and to do very interesting things to build trust in their communities, they just have to focus on that aspect of it and have the wherewithal that they’ve had for over a hundred years to be there and be the consistent presence. These other banks and these other institutions will be in and out. If we stay invested truly in our customers we’ll be there and be profitable. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Great. I just wanted to say as we do wrap up, I think some advice for people would be to definitely switch away from the big banks. Don’t go to the big credit unions. Support your local banks. Part of that doesn’t just mean having a checking account with the local bank, it means using the credit card from the local bank rather than some kind of American Express card that gets you lots of points but harms local merchants. There’s a lot of things you can do to really make sure that you’re supporting that local bank being a thriving institution.

Justin, I’ll just put you on the spot really quick. Is there anything you think people should read; an article, a book that would give them a better sense of this industry? |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | I don’t have anything that’s real topical, but I do think they should spend more time really getting to know where management decisions are made in their community. If you’re banking, like Chris said, there’s a lot of ways to do good things for your bank but the number one question that should drive your decision is, is my relationship purely a data point with my bank or are they actually having humans make those decisions and is the information they have about me less about an algorithm and more about knowing what I need to do in my life or what I want to do in my life and where I’m headed?

I wish I had a lot of great articles and a lot of good things for people to read. I don’t just because our industry is pretty much obsessed with being delved into our individual communities. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Great. Stacy, do you have any recommendations? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Well, I would say that when it comes to moving your bank account, we have some great resources on our site at ILSR.org. If you go to the banking section we have 5 reasons you should bank with a locally owned bank or credit union. We also have a great step-by-step guide to actually moving your accounts because that’s a little bit more complicated than just switching grocery stores. We have some good tools that we point you to how to find a local bank or credit union that’s actually part of your community and doing good stuff in your community. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Wonderful. I would just recommend a book that I have on my bookshelf. I haven’t read yet. The Slate Money podcast had recommended it and discussed it a bit. I thought it sounded brilliant. One of the ways it ties in is it talks about why low income folks actually tend to prefer the loan services, the payday loans that many of us are concerned about for have rapacious interest rates. One of the reasons is they’re used to being gouged to death by the fees from the big banks, and so they prefer these loan terms in which they can get them. The name of that book is How the Other Half Banks: Exclusion, Exploitation, and the Threat to Democracy by Mehrsa Baradaran, I believe. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | I’d be remised to say we aspire to … On our blog, on our website, fnbosakis.com, called Financially Literate to take consumers through these topics on a very consumer level, basic level to build financial literacy in our own customer base. It’s digitally available to everybody, and we’re going to probably update once a month as we get going. Financially Literate at fnbosakis.com is our blog. |

| Chris Mitchell: | That’s O-S-A-K-I-S. |

| Justin Dahlheimer: | Yes. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Thank you everyone for listening. This has been a really fun discussion. |

| Lisa Gonzalez: | That was Justin Dahlheimer, president of First National Bank of Osakis in Minnesota, joining Christopher Mitchell and Stacy Mitchell for episode 16 of the Building Local Power podcast. Stacy is one of our co-directors and runs the Community-Scaled Economy Initiative, and Christopher heads up the Community Broadband Networks Initiative.

As a reminder, check out fnbosakis.com. If you scroll down, you’ll see the Financially Literate tool that Justin mentioned in the interview. Also, don’t forget to go ILSR.org for the tool Stacy mentioned to help you make the switch to a community bank. We encourage you to subscribe to this podcast and all of our other podcasts on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever else you get your podcasts. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter at ILSR.org. Thanks to Dysfunction Al for the music license through Creative Commons. The song is Funk Interlude. I’m Lisa Gonzalez from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Thanks again for listening to episode 16 of the Building Local Power podcast. |

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

If you have show ideas or comments, please email us at info@ilsr.org. Also, join the conversation by talking about #BuildingLocalPower on Twitter and Facebook!

Subscribe: iTunes | Android | RSS

Audio Credit: Funk Interlude by Dysfunction_AL Ft: Fourstones – Scomber (Bonus Track). Copyright 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license.

Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and, for monthly updates on our work, sign-up for our ILSR general newsletter.