Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download | Embed Subscribe: RSS

On this episode of Building Local Power, host Jess Del Fiacco is joined by Neil Seldman, Director of ILSR’s Waste to Wealth initiative, and Captain Charles Moore, author of Plastic Ocean: How a Sea Captain’s Chance Discovery Launched a Determined Quest to Save the Oceans. Their conversation focuses on Moore’s latest article, Mine Landfills Now!, which describes his vision for turning landfills into “resource recovery parks.”

They also discuss:

- The benefits communities can gain from recognizing all waste is, according to Moore, “a resource waiting for recovery.”

- How Moore’s scientific and political background informed his reaction to discovering the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in the late 90s.

- Why a global grassroots political movement is needed to address climate change and plastic pollution and save the oceans.

- Moore’s upcoming projects, including determining a methodology for measuring plastic in drinking water.

“The goal is to use technology to liberate mankind. It has that potential. There’s no question that liberating technology is already in place and has helped millions of people. The question is ‘What about the billions that haven’t been helped by it?’ We can’t ever lose sight of that.”

Contact Captain Charles Moore:

captain-charles-moore.org

cmoore@algalita.org

Algalita Marine Research and Education

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Hello, and welcome to Building Local Power, a podcast dedicated to thought-provoking conversations about how we can challenge corporate monopolies and expand the power of people to shape their own future. I’m Jess Del Fiacco, the host of Building Local Power and communications manager here at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. For 45 years, ILSR has worked to build thriving, equitable communities where power, wealth, and accountability remain in local hands. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Today I’m here with Neil Seldman, who’s the director of ILSR’s Waste to Wealth initiative, as well as Captain Charles Moore, who’s the author of Plastic Ocean and a long-time zero-waste advocate. So welcome to the show, guys. |

| Neil Seldman: | Thank you. |

| Charles Moore: | Thank you. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Yeah. Neil, if you want to get us started? |

| Neil Seldman: | Yes. I will, and it’s a pleasure to have Charles here. Known Charles for many years, and we both coordinate the Save the Albatross Coalition, which is a grassroots organization, and I’ll just let people know that Charles has been a pioneer researcher. He’s continuing his research through several research organizations, which we’ll hear about, and he is an international leader, but he’s also a national leader involved in all aspects of retaining plastic, protecting the oceans, and helping the country as well as the world get to zero waste. |

| Neil Seldman: | Having said that, I’d like to ask Charles to start us off by just indicating what led you to inquire about the garbage patches that you discovered now some 25 years ago. |

| Charles Moore: | Well, it was an accidental kind of discovery, although I hesitate to call it a discovery, because it was just a feeling of unease about seeing so much anthropogenic debris as far from human civilization as you can get. This Eastern North Pacific Subtropical Gyre is huge. It’s probably the largest climatic feature on the planet, and I crossed it in 1997 during the largest El Niño on record, and it was very calm, and that allowed whatever trash was there to float to the surface, and I couldn’t come on deck without seeing some form of human-made debris pass by the vessel, and that happened for a whole week. So as a self-described marine mammal, growing up here on the ocean in Long Beach, California, it just rubbed me the wrong way to have trash be there out in the middle of the ocean. |

| Charles Moore: | So I was involved in researching bacteria in our ocean for the fact that our beaches were beginning to be closed for coliform bacterial levels getting so high that it was a danger to recreate in our local waters, and so I have connections with the research community, and I presented them with this conundrum of “How do I determine how much stuff of any sort is in the middle of the ocean?” because it’s not a fixed place. It’s always on the move, and it’s not like sampling near shore where you can set up a geographical location and go back there and expect to have the same sorts of conditions. These are constantly changing. |

| Charles Moore: | So this high-pressure system, this great North Pacific Subtropical Gyre was a problem for us to determine how to sample it. I got the help of some statisticians at the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project and some scientists there, and we designed a sampling strategy. I wanted to understand it and sample it carefully to get some kind of a feeling for how much is out there, because when I did a back-of-the-envelope calculation, and this was … Still, I was interested in waste at the time. I calculated that if there was a half a pound in a hundred square feet of ocean, it would be equal in the system, this subtropical gyre system, to a year’s deposition in Puente Hills Landfill, which is the largest landfill in California, probably the largest in the United States. If this much trash was floating in the ocean, I wanted to quantify it. I wanted to get some science onto it, because that’s what people listen to. |

| Charles Moore: | I did go back two years later with sampling equipment, and that’s when the discovery was really made, the fact that we had a garbage patch, because what we found was six times as much plastic as zooplankton in the surface waters out there. That means there was more trash than life in the area as far from human civilization as you can get anywhere on Earth. |

| Neil Seldman: | Let me interrupt right there and ask you, because I know that was your originals findings back in the ’90s. What have your most recent findings shown about that ratio, six to one? |

| Charles Moore: | Well, we’re a small research lab, and we don’t have a big staff, and I’m not part of an academic institution, so I can’t tap some undergraduates on the shoulder and say “Go into the lab and look at my samples and tell me how much is there.” So we’re still analyzing our 2019 sample set, and that was a 20-year time series. We’ve seen it going up, but to really establish trends over the 20-year timeframe, we need to finish our 2019 expedition samples, and we haven’t done that yet. But everyone knows that looks around them that trash in their neighborhood wherever they are is going up, and it doesn’t take a scientist to point that out. So the question is “How much?” and “What is it doing?” and we have this new invader of the biosphere. It’s synthetic polymer, which defeats natural decay organisms. That is the real issue to me. |

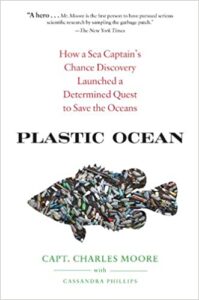

| Neil Seldman: | Well, I just want to point out two things that Charles has written describing his early years in this area, Plastic Ocean: How a Sea Captain’s Chance Discovery Launched a Determined Quest to Save the Oceans. It’s Penguin USA, 2011. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | We’ll have that linked in the post for this episode, so- |

| Neil Seldman: | Oh. [crosstalk 00:06:23]. |

| Charles Moore: | That’s the hardback, Neil, and- |

| Neil Seldman: | Yes, and- |

| Charles Moore: | … the paperback as an extra chapter on the health effect. |

| Neil Seldman: | Yes, which I haven’t seen, but I look forward to it. I also want to point out that just yesterday the Institute published a new important article by Charles called Landfill Mining, which we’ll be talking about in a moment. I just want Charles to let us know before you … What was your education and training that prepared you so that when you saw this garbage patch back in ’97 you were alerted and you knew what to do? If you could just give us a couple of sentences of how you were trained to do this. |

| Charles Moore: | Well, I was trained by my father, who was an industrial chemist. We don’t hear too much about chemistry sets these days as a recreational toy for children, but our family had a laboratory in a used washroom. My childhood was taken up with chemical experiments, and I was a chemistry major at UC San Diego. But I was also aware of our situation, as a political animal, and being part of the world, I realized in the 1960s, the late ’60s, that this war in Vietnam was evil and untenable, and rather than pursue a continued degree and get a PhD and become a chemist on some corporate chemistry staff, I decided to break away from academia and go out on my own with a political agenda, which was to stop the war in Vietnam and exercise some vocal control over what happens in our community. |

| Charles Moore: | I was equipped with science, but I was also equipped with a political consciousness that allowed me to put two and two together and say “This is a political problem that we have trash in the middle of the ocean, not just a scientific study problem.” That’s kind of where I came from, and then I just … The ability to see the need for a new field of science, and that’s what we’ve developed over the years truly. When I started out I could not find one paper a year on the subject of plastic pollution in the ocean. Now we have a thousand papers per year, plastic in the ocean, so we really did develop a new field of science. |

| Neil Seldman: | Well, this is a great statement for young people to hear, combining scientific inquiry with political values, normative values, so thanks for summing that up for us. I want to get back now to what I mentioned earlier, that Charles recently did a piece, a long piece, which we published on landfill mining, and I love the theme. I’m restating it, but it basically is garbage dumps into resource-recovery parks is the goal, and this is an international goal, not just for the United States, and Charles, I was just wondering if you could give us a few minutes of what you observed as you went around the world looking at these dumps and came up with your ideas for how to deal with them. |

| Charles Moore: | I’ve been on a speaking tour, what I call the Plastic Pollution Conversation, because we are in the age of plastics, and we live behind a plastic curtain of ignorance, and I was drawing back that plastic and informing people about the product that defines our age. The stone age is defined by stones, the bronze age by bronze, and people in the stone age I think knew more about what to do with a stone than people in the plastic age know what to do with their plastic. It’s so unique, so variable, so different from anything we’ve been accustomed to, and to have it in such huge quantities and have it in such huge varieties, people just don’t know where it comes from. They don’t know how it’s made. They don’t know what its effects are, and largely because they’re so intimately in touch with it, they consider it to be a kind of inert material, innocent in a way, and that’s not the case in any sense. |

| Charles Moore: | That was my goal in touring was to draw back that plastic curtain of ignorance, and of course a lot of the folks that wanted to hear about it are folks that are involved in the zero-waste movement and involved in recycling, and I was able to see some very unique efforts in countries I visited, especially in my sailing trip to study the South Pacific Garbage Patch, and we sampled that in 2017. Then I came up the coast of Chile, and that’s where I saw the Atacama Desert in Antofagasta being reclaimed by a fantastic couple who turned a desert wasteland into a resource-recovery park. Parque Reciclado Ecorayen is an amazing effort where they’ve built an oasis in the middle of the desert all with reclaimed materials. Seeing something out of nothing made me realize that there’s no excuse for throwing everything away. |

| Charles Moore: | There’s a lot of areas that need to have reclaimed materials as their infrastructure, and this park is powered by reject solar panels. A lot of times things are rejected. We know this in the ugly fruit movement and the ugly vegetable movement. Things are discarded for looks, not for any significant, real problem with them, and they’re still functional. Many products that are headed for landfill really only need a little help to become those useful products that they were designed to be, and that’s what captured my attention at Parque Reciclado Ecorayen. That’s a very important example of what can and should be done with our discards. |

| Neil Seldman: | Charles, does that project have government support? Or is it completely private sector community based? |

| Charles Moore: | No. It’s completely private sector community based. It’s very rare to have government in the forefront of materials recovery or anything else, because it’s attached to the status quo. The government survives on the status quo, and it wants to see 10, a hundred, or a thousand examples of anything new already having been successful in order to risk their precious government resources on doing anything new. |

| Neil Seldman: | What you say is an exact description of what I found. I did a project for the World Bank in the 1980s. They sent me down to Medellín, Colombia where there’s a big landfill in the middle of the city with a lot of waste pickers, and we laid out a strategy to make them more efficient, get them conveyor belts, tables, coverings during the rain. The goal was to make them more efficient to get their children out of the dumps and into the schools, and the World Bank accepted the project, but the local politicians wouldn’t, because they figured if the waste pickers got organized, they’d be a political force, and the project was discarded exactly in the dynamics that you pointed out. So my next question is … Well, it’s a point you may want to comment on is that these technical solutions need political support, and it’s both a technical and political problem, as you were laying out earlier. |

| Charles Moore: | Well, I say in my disclaimer to the article that it’s an effort to reclaim utopian possibility, and people will point to zero waste as a utopian goal. As a matter of fact, zero-waste advocates constantly have to defend the concept of zero, because everyone knows nothing is perfect. So when we say zero waste, we have a slogan, “If you’re not for zero waste, how much waste are you for?” and the answer would be, well, people are for whatever amount of waste allows the status quo to continue to exist. |

| Neil Seldman: | Exactly. |

| Charles Moore: | The status quo is moribund. It is unable to cope with the realities of the 21st century. The forces that have created this immense wealth and this fantastic technology have been unable to organize it for the benefit of humankind in such a way that it doesn’t leave, and I’m going to use the term billions, billions of people out of the equation. This is not sustainable to have a world in which billions of people are expected to scrap on discards and claw their way out of poverty with no help. My utopian vision is coupled with the reality of political intransigence, political reaction, and to be quite frank, political stupidity. |

| Charles Moore: | The goal is to use technology to liberate mankind. It has that potential. There’s no question that liberating technology is already in place and has helped millions of people. The question is “What about the billions that haven’t been helped by it?” We can’t ever lose sight of that. The stock market rallying in this time of immense suffering is an example of how as an economy lose sight of the poorest among us, and we can’t do that if we’re going to have a sustainable society going into the future. Why? Because we’ve already created a determinant negation of that society with climate change and plastic pollution. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Could you talk a little bit more about what that utopian vision looks like, either for the recovery parks in particular or zero waste generally? I mean, what are some of the direct, indirect benefits to communities if they were to move away from landfills towards recovery parks, for example? |

| Charles Moore: | Well, first of all it’s space. If we continue down the road we’re on now, we will be living between landfills. Landfills are happening even without being organized as landfills. Things are just filling up with our trash. The beaches are becoming landfills. The ocean … I call the Great Pacific Garbage Patch a seafill in the middle of the ocean. It’s filling up with our garbage. So we’re going to have a lot more space if we stop wasting. We’re going to have room for the people on the planet to live a more fulfilling life, and the way we do that is to always remember that everything is a resource waiting for recovery. All products can be reincarnated. We reincarnate agriculture biologically. We have no problem with that. We know that our compost grows new plants. |

| Charles Moore: | So my vision is two-fold. One, to mimic the natural world’s biological zero-waste system, which a forest is a zero-waste economy. No one goes into the forest to fertilize the trees so we can have 200-, 500-year-old trees. They take care of themselves. It’s a zero-waste economy. It’s an economic model. Now, with technology there’s problems because many technological products are difficult to handle in a circular, steady-state type of economy, but that’s where my vision for the resource-recovery park has the resource-recovery university. We don’t give nearly enough time at academic institutions towards the science of recovery of resources. |

| Charles Moore: | We need a Nobel Prize for resource recovery. We need a faculty of recycling and resource recovery. We don’t have that. That’s why I think, as part of making the recycling of materials sexy, we need to have a university at the landfill, which is no longer a landfill. It’s a resource-recovery park, but we build it with the materials from the landfill. We’re going to mine these landfills, build these universities that are going to focus on recycling and resource recovery, and we’re going to do it with the materials that are there, because truly we’re going to go backwards from building a city and then building a landfill … We’re going to go from having a landfill to building a city. |

| Neil Seldman: | I love that image. I also want to point out you mentioned zero. The actual term zero waste is what we use is we say is zero waste or darn close to it. So we realize that we can’t get to zero, but in the United States now we’re at one third recycling. If we would double that or get it to 80 or 90 percent, the impact would be tremendous, even if we don’t get to actual zero. |

| Neil Seldman: | Charles, I wanted to add to your response to Jess’s question by saying that not only the space benefits and the other benefits you mentioned, but a zero-waste society would give more time for people to do whatever they wanted, do more work, do more recreation, and money. A zero-waste economy is less expensive. But the most important thing that a zero-waste economy does is to focus people not on material possessions, but on their relationships with their family, with their neighbors, and of course with the political system. |

| Neil Seldman: | So if I could ask another question … Thank you for that, Jess. I want you to let people know. What organizations do you network with? What organizations should people be paying attention to that you help them and they inform your work and we have a better synthesis after everyone is putting in their input? |

| Charles Moore: | Well, in my travels I did get an honorary PhD from a university in British Columbia, Canada, and there I noticed that there was some very progressive thinking about refill stations instead of having … They were fighting the contract that they had with the vending machine operator, and the vending machine operators of course want to stock with all kind of disposables, but the students wanted to put in washing machines and places where you could leave your cup, pick up another cup as an alternative to the vending machine culture, and I think universities are a good place to start. I think the Post-Landfill Action Network that seeks to make zero-waste universities is a good group to network with. |

| Charles Moore: | As a matter of fact, the organization I started, Algalita Marine Research and Education, has a director of partnerships. We don’t really focus on getting ourselves in a prominent position. We focus on maximizing our partnerships’ ability to work, because truly when we’re dealing with climate change or with plastic pollution, we’re dealing with a global problem in which everyone is part of the problem and everyone is part of the solution. |

| Charles Moore: | There’s a new politics. When the German philosophers talked about the Weltgeist, the world spirit, it was mostly about the spirit of Western civilization. Now we have a new world spirit connected by the internet that is going to make a political reality come true, which is a world political movement, and that’s what will be required to deal with climate change and what will be required to deal with plastic pollution will be a world consciousness, and that is obviously subject to manipulation. Unfortunately the algorithms that the corporate social media folks use associate like with like and give people more of the bad stuff if they’re already in a bad way. |

| Charles Moore: | So we’re not at the point where it’s a kind of panacea, but there will be efforts to make world political movements more rational and to attack world problems in a way that will actually make a difference, because you know and I know that all the conferences on climate change that have taken place have not produced a reduction even in the production of carbon dioxide, and carbon dioxide production continues to go up. So we haven’t turned it around. |

| Charles Moore: | The traditional political organizing that is taking place is not producing results that can deal with this, like all the determinant negation of our capitalist system, which is that as it continues to profit by this wonderful technology, it creates conditions that make it unsurvivable in the future. It’s creating a climate situation that is incredibly sporadic and dangerous, and plastic pollution is creating a situation in which we now know that zooplankton in the ocean cannot pass the polyester fibers from our clothing, and that’s going to clog up the basic food source in the ocean. |

| Charles Moore: | So this is what I mean by determinant negation, and like I say it in the article, like bacteria consuming agar-agar on a Petri dish, they eventually get to the point where there’s more excrement than there is food, and their civilization collapses. That’s what we’re facing. That is a future that can only be avoided by world political action. |

| Neil Seldman: | Thank you for that, Charles. I was remembering as you were speaking about the climate crisis, plastic crisis, and actually the food crisis. I was thinking, back in the late ’60s when we had the first emergence of environmental consciousness in the country, the Cleveland River was on fire, the Santa Barbara oil spill, and the inversions around Thanksgiving and Christmas in 1969 alerted people, and the question is … Right now we’re facing even greater threats. Will the political systems respond? I think that is the question of our age. |

| Charles Moore: | No politician, no matter how progressive, can get us out of this mess. This is going to require grassroots political organizing on a global scale. |

| Neil Seldman: | Absolutely. I meant to say that we need the grassroots effort to continuously press whosever in power, and with Biden we have an opportunity, but it’s up to us to keep that pressure on. I do understand that. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Are you involved in any, I don’t know, projects or organizing right now, or anything you’re starting or excited about? |

| Charles Moore: | Yeah. Neil mentioned a food crisis. I might add to that a water crisis. It turns out that these plastic fibers are in our water, and we’re drinking it, and we’re getting it in our food. We’re getting it through the air. So my latest initiative was to start an organization that could drill down into the nano scale, which these particles of plastic don’t go away. They just break down until they’re nano scale, millionths of a meter size plastic. |

| Charles Moore: | We’re going to have to regulate plastic pollution in our tap water, and I’ve started a laboratory, and in conjunction with international labs from China and Europe, from around the globe, we’re developing methods now to determine how much plastic is in our drinking water so that governments can begin to regulate the sources and causes of this type of contamination. |

| Charles Moore: | So the Moore Institute for Plastic Pollution Research just held a GivingTuesday fundraiser. We did pretty well, and we go to the lab every day. We sit on that microscope, sit on a chair in front of the microscope, and look at samples of water and pull out little bits of plastic, and these are standardized amongst the 40 labs that are participating in the study. They’ve all received a standardized hundreds of particles of plastic in clear water, and the idea is to find out how well they coordinate in order to have a standardized methodology that we can rely on to then create regulations when we determine how much plastic is in our drinking water. |

| Charles Moore: | So I started the Moore Institute for Plastic Pollution Research, and I’m working closely with my former institution, Algalita Marine Research and Education, and that’s the latest initiative I have. I should mention however too that in times of COVID, I always had a hand in the biological regenerative side, and I started Long Beach Organic to turn vacant lots into organic community gardens, and we’ve now started a program with Long Beach Organic to dedicate a certain part of all our community gardens to growing food for people in need during COVID, and I just got them a $10,000 grant so that they could expand that project and get food out to the community that’s organic and fresh and can be combined with all the canned goods and other stuff they’re getting. |

| Charles Moore: | So I have a two-pronged approach. My first handle at the dawn of the internet was Land and Sea, and I believe that we can’t really fix what’s in the ocean without fixing what we do on land, and that requires organic land management, requires regenerative agriculture, and requires that we start giving space to cities to produce their own food. The city of Paris was self sustaining early in its history in terms of agriculture, and we need to have self-sustaining cities now. Now folks are doing it in high rises. They’re doing it under glass. They’re doing it in open space and vacant lots. |

| Charles Moore: | I want to combine both our land approach to zero waste and the study of the sea to create this kind of knowledge base that we need. Incremental change is now our friend in a time of crisis, and that’s why I believe, and I know you agree with me, Neil, that radical political change is a must for human longevity. |

| Neil Seldman: | Yes. We have to get to the root causes of things. I just wanted to add what Jess asked about your itinerary for this coming year, 2021. Will you still be going out on oceans during 2021- |

| Charles Moore: | Yeah. |

| Neil Seldman: | … making your expeditions? Okay. |

| Charles Moore: | There’s a new initiative by a local resource organization I mentioned before. The Southern California Coastal Water Research Project, a joint powers authority, works with the waste dischargers and the various government entities that deal with water, the water boards. They’re wanting to study and get baseline data on how much plastic is in our local water area that we call San Pedro Bay. There’s two major urban rivers, the San Gabriel and the Los Angeles River, discharging there. They want samples off of those rivers, and I think it’s a three-year project, where they’ve asked my vessel to be the support vessel for this effort, because I’ve designed the epibenthic sleds they’re going to be using to sample plastic near the sea floor. I’m building a new one right now, and we’re going out today after this interview to begin practicing with some of our new research equipment. |

| Charles Moore: | I will be active on the water. I’ll be active in the lab, and I’ll be active in my garden. Every Sunday I have a local farmers market that can’t be more local than being in my front yard, and I make a little bit of money every weekend with passersby. I put out my surplus food I grow for the community. I find out what their interests are, what they like, and I grow it. I have 46 years of agricultural experience in organic urban farming, and Captain Charlie’s Urban Farm is inspected by the county agricultural commissioner. I have a seller’s permit, and every Sunday from 10:00 to 4:00 I put out a table with my goods on it, and I also let people harvest their own if they want, and I harvest as they come. So you can be any fresher than that. |

| Neil Seldman: | A true Renaissance man, a national and international treasure. The picture on the book … It’s a wonderful graphic showing a fish contaminated by everything we’re throwing out, and there have been many other pictures of Albatrosses have been dissected and showing why they died with all this, and I’m reminded of the great poster that Greenpeace produced in the ’80s when the Mobro garbage barge was moving around the ocean, “Next time, recycle,” which became an iconic poster at university dorm rooms, et cetera. So I wanted to compliment you on the graphic on the book. |

| Neil Seldman: | Getting back, if you don’t mind, to the Mining the Landfill, your most recent publication, have you … Besides describing the project you did, are you familiar with any similar projects in the United States that have been trying to build these resource-recovery parks out of recycled materials? |

| Charles Moore: | I do know of one in Hawaii that has made a fairly decent park at the Waimea Transfer Station and has a store where they sell reusable materials, mostly clothing and electronics, anything that’s in good enough condition, because a lot of things that come to the landfill, as I said before, are in pretty good condition and with minor repairs can be made usable again. So this transfer station is a nice model because when people come there, it’s not just one receptacle to dump stuff in. It’s a series of receptacles that have cardboard, mixed paper, glass, metal. |

| Charles Moore: | You have all this separation going on by the community. It’s especially useful in communities that don’t have curbside, because curbside tends to want to have just one single recyclable bin, but if you have communities that take their waste to the transfer station, you can have them separate it at the transfer station. So you get several different kinds of materials without anybody but the producer of that waste having separated it. |

| Neil Seldman: | Yeah. Let me point out that a good friend of both of ours, Dan Knapp and Mary Lou Vandeventer at Urban Ore … They just negotiated … It’s a reuse company on three acres in Berkeley. They just won a contract with a service fee. Every ton they pull out of the materials going through the transfer station, they get $46 a ton, which is what the city would have had to pay to landfill it. So there are excellent examples. |

| Neil Seldman: | I just want to mention two more. St. Vincent de Paul in Eugene, Oregon has a whole network of repair operations, appliances, mattresses, furniture, textiles, and then a new phenomenon in Appalachia called the ReUse Corridor. It serves Southern Ohio, Kentucky, West Virginia, and parts of Pennsylvania where communities are getting together to aggregate mattresses, electronic scrap, and then they’re contracting with end users and processors. So the reuse is happening in the United States. We would love to see the full resource-recovery parks the way Charles has described them, and as Charles said, we’re all in a work in progress making progress with lots of barriers. |

| Neil Seldman: | Before we leave, we usually ask our guest “What two books or two articles do you think are important for people to read at this point?” Charles, in your opinion. |

| Charles Moore: | Well, do people still read? |

| Neil Seldman: | Yes. I think some of us still do, Charles. |

| Charles Moore: | I thought it was all emojis now. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | We’ll take an emoji suggestion too if you’ve got one. |

| Charles Moore: | You know, I like Animal, Vegetable, Miracle by Barbara Kingsolver, an Appalachian farmer that moved from Tucson, Arizona, decided to live on everything that they could produce. She has a very good perspective on zero waste. It’s the agricultural side, very good. Then there’s another one called Utopia for Realists that talks about utopian ideas not being any more utopian. That was my professor at UC San Diego, Herbert Marcuse, has written several books. I recommend you to read any of those. M-A-R-C-U-S-E. His take on technology was that it’s wasted if it’s not used for the utopian possibilities that it presents, and that’s what we’re doing. We’re wasting technology, not only goods. We’re wasting our ability to liberate humanity. |

| Charles Moore: | Now, these miracles of technology can be shared, and that was my purpose in writing this article. I talked about waste pickers on one side of the landfill and then modern technology on the other side, and when they meet in the middle, the landfill would be completely mined, would have all the resources taken out. Now, and I think that’s the kind of utopian vision that we need, that we can unite the technical with the artisan and create a world in which artisan possibilities are liberated by technology. So you don’t have to be a salve to your trade. Your trade can liberate you through the technology. That’s my vision, and that’s what I tried to communicate in this article. |

| Neil Seldman: | Well, Charles, I can say, being a long-retired professor of political theory, that Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s first discourse in the 1750s made the same point, that all the science and technology that we’re advancing does not do anything if it doesn’t help the common person. So we’re both abiding a long tradition in Western political thought, and Charles, you’ve animated it. You’ve given us examples and inspiration. I really appreciate your time. So thanks again, Charles. Have a great weekend. |

| Charles Moore: | Neil, I want to thank you for sticking with the Save the Albatross Coalition. A lot of people don’t realize that the Albatross is in so much danger from eating plastic waste. Thanks for continuing to work on that, and we hope for big things for the Save the Albatross Coalition in the future. |

| Neil Seldman: | Yeah. I’ll just give a quick update. The Albatross Coalition is working with lawyers to develop municipal lawsuits against the big polluters for suing for funds to clean up the beach, and that’s one of among a number of projects from Save the Albatross Coalition. I want to give a shout out to Laura Anthony, who’s the staff coordinator for the Save the Albatross Coalition as well. She’s based in San Diego. |

| Charles Moore: | Thanks again for the interview. |

| Neil Seldman: | Thanks. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Thank you. |

| Charles Moore: | All our best to the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. |

| Neil Seldman: | Thank you again. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Thank you. |

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

If you have show ideas or comments, please email us at info@ilsr.org. Also, join the conversation by talking about #BuildingLocalPower on Twitter and Facebook!

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | RSS

Audio Credit: Funk Interlude by Dysfunction_AL Ft: Fourstones – Scomber (Bonus Track). Copyright 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license.

Photo Credit: Pickist

Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and, for monthly updates on our work, sign-up for our ILSR general newsletter.