Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download | Embed Subscribe: RSS

In this episode of Building Local Power, host Jess Del Fiacco and ILSR Co-Director Stacy Mitchell are joined by Brad Lander, who represents Brooklyn’s 39th District on the New York City Council. Brad shares his perspective on how the pandemic has affected NYC neighborhoods, the parallels he sees between now and past crises — including the 2008 financial crash and the city’s near-bankruptcy in the mid-1970s — and how the city can avoid repeating past mistakes.

They also discuss:

- How the city can protect small businesses and families from being priced out of neighborhoods by spiking rents and the financial impacts of the pandemic.

- How a city-run “land bank” would strengthen communities, boost economic development, and expand affordable housing by keeping property in the hands of non-profits and co-ops instead of for-profit developers.

- The successful community land trusts in Burlington and Albany that helped inspired this work and how other communities can pursue social ownership models.

“Our model for community economic development for affordable housing construction and for economic development investment has really been very substantially for-profitized, so that 80% of the subsidies the city gives out for affordable housing go to for-profit private developers. And then lo and behold, 30 years later, when the mortgage is up, they’ve got the right to take it to market, and we wonder where the affordable housing went. But we don’t have to make those choices. We could pull our affordable housing back.”

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Hello and welcome to Building Local Power, a podcast dedicated to thought-provoking conversations about how we can challenge corporate monopolies and expand the power of people to shape their own future. I’m Jess Del Fiacco, the host of Building Local Power and communications manager here at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. For 45 years, ILSR has worked to build thriving, equitable communities where power, wealth, and accountability remain in local hands. Today I’m here with Stacy Mitchell, who’s the co-director of ILSR, and we’re joined by Brad Lander, who represents Brooklyn’s 39th district on the New York City Council. Welcome to the show, guys. |

| Brad Lander: | Thank you so much. I’m a big fan, so I’m really honored to be here. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | We only let big fans come on the show so they can praise us the whole time. That’s the secret. Before we get started, I also want to note that you’re involved with Local Progress, which is a network of progressive local officials around the country, so we might touch on that a little bit too. But Stacy, anything you want to say before we hit the ground? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | No. I’m so glad you’re here. I think we should dive right in. I think what’s on my mind is thinking about the huge impact that COVID has had on New York City, both people and the business community. I am imagining that there are a lot more vacancies than there used to be when you walk around city streets. I’ve read that hundreds or maybe even thousands of businesses have shuttered. Can you talk about what you’re seeing, particularly at the street level and with local businesses, and how the fabric of neighborhoods has changed? |

| Brad Lander: | Absolutely. Thank you so much for having me on. I think what ILSR is doing all across the country is really inspiring. And that model of supporting communities to take more control democratically is really powerful, and an urgent time for it. So yeah, I mean, New York City has been so hard hit, and I still think even though you see it in vacant storefronts that in most of our minds, we’re back in March and April hearing those sirens. |

| Brad Lander: | So the death toll and how unequal that death toll was, we’re all holding it. And we have to figure out ways to deal with the economic devastation, but I think both the human devastation and just how unequal it was, along the lines of race and class we’re still sitting with also. So yes, I mean, commercial property broadly, our retail storefronts, our office buildings, our hotels are really dramatically devastated. We got information yesterday that the projections for next year are that our property taxes are expected to be down $2.5 billion, a 20% decline- |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Wow. |

| Brad Lander: | … almost all driven… Very little of that is residential to clients, even though obviously lots and lots of people are facing eviction or struggling with their mortgages, but it’s overwhelmingly commercial properties. Now, I think at the neighborhood level, I’m here in Brooklyn in my neighborhood. And if you walk around, you can see it in the storefronts. Our bodegas are open, but so much else is closed. And we’ve obviously seen this. |

| Brad Lander: | We opened up our streets, so a lot of restaurants have outdoor dining. And they’ve even built shelters and huts for winter outdoor dining. We’re going to have an ability to reinvent our streets to actually work more for neighborhood businesses. But I think probably somewhere between a quarter and 40% of small businesses are at risk of closing because got so much back rent that can’t pay. We still have very, very serious restrictions, as we need to amidst the second wave, on indoor dining and other businesses. |

| Brad Lander: | Meantime, obviously lots of people who did commute into Manhattan to work in their offices are continuing to work from home. Most of our hotels are closed. But I’ll end with this. And I think of all your work here. Our residential streets are so full of commercial delivery vehicles. The ways that it’s been transformed, you’re not only seeing closed storefronts, but just an incessant flow of Amazon and FreshDirect trucks. And you can see the changes of our economy devastating on both sides, both the loss of small business and the loss of jobs, but also the increase in kind of monopoly control right here on our streets. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | What do you think the role of a city government is with an issue like monopoly? I mean, seeing all of those Amazon delivery vans, I saw some reporting out of a local newspaper. I think it was from the city, a neighborhood newspaper that was showing pictures of Amazon delivery vans essentially commandeering whole blocks, and setting up and sorting boxes, basically taking a city block and turning it into a warehouse distribution hub, which I don’t see UPS or other delivery operations doing. Certainly local businesses aren’t allowed to just go occupy the sidewalk. Should the city be doing more to address these issues of monopoly power? And if so, what? |

| Brad Lander: | Yeah, absolutely. We’ll come back to talking about what we can be doing to better support our small businesses and keep building a diverse and strong economy. But the last mile distribution in particular is just the Wild Wild West right now, and localities may not be able to get at the heart of the monopoly issues, but they can sure get at a whole range of public interest, worker protection, consumer protection, and neighborhood health and safety issues that we haven’t done anything near enough about. |

| Brad Lander: | So I’ll start by the fact that there’s a giant Amazon distribution center on Staten Island where workers report just horrific conditions during COVID, but working conditions in general. And it’s absolutely the responsibility of states and cities to demand decent working conditions for their workers. There’s a lot more that we could be doing there. A lot of those Amazon Flex delivery trucks are taking advantage of the gig economy loopholes. It’d be best if that was fixed at the national level, but states can fix it too, and we don’t have to be cowed by Prop 22. |

| Brad Lander: | So we’re looking to New York City and there’s pressure on New York State as well to do something about that. But I’m looking at some regulations around last mile distribution because we don’t have anywhere near enough regulations on those last mile distribution centers. They come from a giant set of warehouses and more and more all over our cities. Even within a couple of miles from where I’m sitting, I think five of them are now permitted, but we don’t have good permitting rules. So they didn’t have to do a special permit application. There’s no license required. They don’t have any information on how many trucks are going in and out, where they’re going. Are they going to be electric? |

| Brad Lander: | What are going to be their impacts on the environment in the neighborhood? [inaudible 00:06:45] clarity about the job quality or about traffic. And all of those matter enormously in local communities. It’s a pretty straightforward use of the police power of cities to stand up a new set of regulations to get at all of those, both the workers’ side and the environmental side of these last mile hubs. That’ll be true whether they’re Amazon hubs or whether they’re independently contracted, so whether or not they’re in the monopoly or not, but it’s so critical. If we want neighborhoods that feel like neighborhoods and not like truck distribution centers, then we’re going to have to find a new set of regulations to do it. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Yeah. Going off of that and kind of looking towards the future of things, kind of what comes after this, you recently wrote this piece in the New York Times called How to Avoid a Post-Recession Feeding Frenzy by Private Developers, which seems like an important thing to do. And in that you compared what the city is going through now, OUR current recession with what New York went through, reaching near bankruptcy in the mid-70S, and then the financial crisis in 2008, and you kind of drew parallels between those moments and now. Could you talk about some of those parallels that you saw and why they have you concerned? |

| Brad Lander: | Absolutely. So New York has been through those two relatively recent crises. In the 1970s, we faced a massive fiscal crisis as people were moving out of the city to the suburbs, and the city’s tax base was cratering. And then again, after 2008, the foreclosure crisis led to just massive amounts of properties, in that case mostly homes, being foreclosed upon. And each time it was a really cataclysmic threat to the city with threats to the economic and fiscal health. |

| Brad Lander: | Unfortunately, both of those times, the response of our city leaders was to look to the private [inaudible 00:08:33] and say, “We’ve got to batten down the hatches, cut the social safety net, lay off city workers. That means not adequately maintain our parks or our subways, and instead hope that if we give tax breaks to businesses and developers, they will create jobs and somehow restore the economy.” And a lot of those leaders were praised as the champions who saved New York city, but the consequences were really devastating, both the austerity that that imposed. |

| Brad Lander: | The City University of New York stopped being free, stopped being a vehicle for working class and low-income kids to get a chance to thrive and create the next great business. And then it also had a bunch of impacts on property ownership. So especially after the Great Recession, all of those homes that had had largely Black and Latino homeowners who had been sold predatory products and then had their homes foreclosed on. |

| Brad Lander: | The folks who scooped them up, by and large, were private equity firms and real estate investment trusts, some of whom had actually participated in the run up to the Great Recession and in subprime lending, and then on the back end were able to buy up properties at discounts and then look to flip them back out in a way that has continued to make our housing market less affordable and not benefit neighborhoods. |

| Brad Lander: | So that’s how we don’t want to do it, is sort of that way that it was done out of the 70s and out of the Great Recession. Luckily, we do have some other lessons in our history in New York City, because after the Great Depression and after World War II, our leaders really chose a different path, one of investing in public goods, investing in the subways, in the City University of New York, in public housing, in what we here call Mitchell-Lama housing, which are multifamily cooperatives, what are called limited or shared equity cooperatives, where folks could buy in for a modest amount, act as cooperative homeowners, and when they leave, still sell at a modest amount. |

| Brad Lander: | So it doesn’t go on the market at the market price, you don’t have speculation, but you make homeowners in a durable way. And more than 50,000 New Yorkers in that time were able to become cooperative homeowners. So that model of investment in public goods as a platform for shared economic growth is also in our history. And I really think that this moment, given the challenges of inequality, given the challenges of the climate crisis, given the challenges to our democracy, we have a stark choice. And that article was designed to say, “Here’s a way forward to take that better, more public-minded path.” |

| Stacy Mitchell: | What would it take to take that path? I mean, both as a matter of policy, how would you structure that, but also as a matter of politics? |

| Brad Lander: | Yeah. So I’ll do politics first, and then I’ll be glad to get into the tools. New York City has got elections coming up, as a lot of other places do, but it happens that our democratic primary is coming up in June. And we’re going to make this choice. There are some candidates in the city-wide and council races and mayor’s race who are articulating really both of those paths. We have the guy who was the vice chairman until recently of Citibank who just got the race, and he announced a $5 million haul in his most recent fundraising. It was this amazing line in The Times. It includes [inaudible 00:12:01]. Contributors include 20 billionaires, including some people whose wealth goes back to the Ottoman Empire. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Wow. |

| Brad Lander: | And so it’s pretty clear that that’s going to be… Is it going to be a group of people saying, “Turn it over to the business community, and let’s try that path of austerity and real estate tax breaks again”? But there are also candidates running with this bolder vision. And I think we can do it right now. I come from the community development and affordable housing world. Before I got in politics, I ran a non-profit community development corporation in Brooklyn called the Fifth Avenue Committee. |

| Brad Lander: | And when I got into that work in the early 90s, there wasn’t much private sector interest in low-income neighborhoods throughout New York City. And so the work to save our neighborhoods from abandonment was grassroots. It was non-profit, it was cooperative. It had the spirit of Banana Kelly up in the Bronx taking over abandoned buildings and making them community assets. And you could feel a kind of economic democracy that brought back neighborhoods. |

| Brad Lander: | But what’s happened in the decade since then, is our model for community economic development for affordable housing construction and for economic development investment has really been very substantially for-profitized so that 80% of the subsidies the city gives out for affordable housing go to for-profit private developers. And then lo and behold, 30 years later, when the mortgage is up, they’ve got the right to take it market, and we wonder where the affordable housing went. |

| Brad Lander: | But we don’t have to make those choices. We could pull our affordable housing back. So I propose creating a New York City land bank that could acquire some of the distressed properties rather than having it bought up by private equity funds and vulture funds and bottom feeders. I propose any city-owned land that we’re disposing for affordable housing or economic development go to non-profits and co-ops rather than for-profit private developers. |

| Brad Lander: | And I mentioned that 80/20 split where 80% of the subsidies go to for-profit developers. I just want to get back to 50/50, so at least half the money is in the hands of non-profit community development groups and co-ops. And I think if we took those steps and a few others, we could have a focus on a recovery that creates jobs, the hat creates affordable and supportive housing, that makes spaces for artists, that makes more room for small businesses, but by increasing the footprint of various forms of social ownership and community control, that really could point a strong economic way forward, but just so much more democratic, equal, vibrant, inclusive way forward. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Personally, I don’t know a whole lot about land banks, but I’m curious if you’ve kind of seen them succeed in other cities around the country or elsewhere, if there’s other models that you’ve kind of looked at to shape what you’re imagining for the city? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | For listeners who’ve never heard that term, just a little orientation would be great. |

| Brad Lander: | Great. And I’ve been using two different terms here, and they’re a little different from each other. One is a land bank and one is a community land trust. So let me quickly describe each of those. A land bank is a pretty simple concept. It’s just, it would be controlled by the city of New York. So you’d have one for the whole city, but basically it could acquire property and then transfer it to publicly beneficial use. |

| Brad Lander: | So a real simple example right now is all these vacant hotels. We have so many hotels that are right now closed, and we think that more than 20% of them and maybe as many as 40% of them won’t reopen. Right now, obviously they just have this very long period of no income, but we know New York City’s tourism is going to come back, but it’s going to come back slowly. It’s not going to be back to normal even after the pandemic is done. And so for at least the coming years, there’s going to be a reduced need for hotel space. |

| Brad Lander: | Meanwhile, we have 60,000 homeless people in New York City. So it’s a pretty obvious public policy problem-solving solution to turn some of those hotels into permanent supportive and affordable housing for homeless and low-income New Yorkers. But to do that, we have to acquire them from private actors and get them into the hands of non-profit supportive housing developers. And the land bank is the vehicle that you would use to do that. |

| Brad Lander: | Rather than bidding against private equity funds that might scoop them in and hope to do something different with them later, the city’s land bank would acquire them, and then we could use them for a little while for a range of different things, but make plans, use public capital to redevelop them as supportive housing for homeless and low-income families. And the land bank is sort of the middleman in that transaction. |

| Brad Lander: | A community land trust is generally a neighborhood-controlled entity. You can have city-wide ones like the Burlington Community Land Trust, which is maybe the most famous, but in New York City, which is so big, we do it at the community level, and that’s a non-profit entity that owns land, and in some cases own buildings as well, in a way that holds them permanently in trust as a public resource, preserves their affordability and their community value, but leaves room for things to be going on in them that are sort of different from each other. |

| Brad Lander: | Some might be cooperative home ownership with those limited resale restrictions. Some might be rentals by a non-profit community development corporation. Some might be supportive housing units for formerly homeless families. Some are retail spaces for neighborhood retail businesses. But the ownership is with the community land trust so that when they come up for a new sale or the end of a lease, they don’t go to market and you lose all of the public benefit in them. |

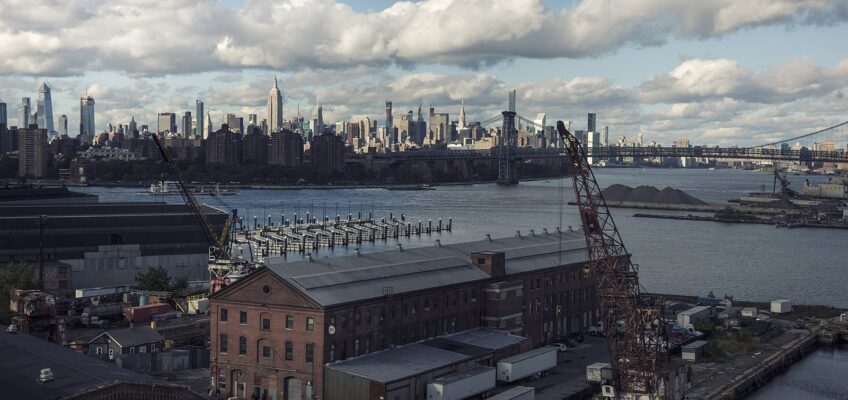

| Brad Lander: | So it’s a city-wide land bank concept with a network of many, many different kinds of actors in the marketplace, community land trusts, as well as non-profit affordable housing groups and housing co-ops. That’s the sort of flourishing social ownership ecosystem that we’re lucky already to have a lot of that here. We have 65,000 of those Mitchell-Lama co-ops. We have, I gave it as an example in The Times article, the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which is an amazing story. |

| Brad Lander: | The Brooklyn Navy Yard is just what it sounds like. It was created to build ships. It was where an enormous number of the Navy’s ships were actually constructed, and it stayed that way into the 1960s, but then it was decommissioned by the Navy. And for a while, it was a little bit like the Wild West, like every city agency that had a fleet of cars tried to grab some piece of it to park their cars, and it became a kind of abandoned parking area. And it’s easy to imagine that what could have happened was that it would have been sold off for condos. That’s what happened to a lot of vacant land. And this is on the water, so it’s got good views. |

| Brad Lander: | But kind of just by good luck in the mid-1990s, an idea was hatched to create the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation, public-private. City continues to own the land, but a mission-driven non-profit operates it under contract with the city, with the goal of making space for businesses that create good jobs for New Yorkers. And it’s amazing the different range of companies that are in there, folks that are doing all kinds of creative technology work. |

| Brad Lander: | During the pandemic, they actually produced a ton of PPE and test material when we couldn’t get it. But it’s all kinds of light manufacturing, creative arts. There’s actually a movie studio, hundreds of businesses and tens of thousands of jobs, lots of them who would not be able to get stable long-term leases in much of the property in New York City, which is privately owned, and manufacturing has really been pushed out in favor of higher rent paying office and retail uses, and have been able to thrive in the Navy Yard. So that’s what we want more of, and that’s what these ideas of having a land bank and land trust are going to do. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | We’ll continue with our conversation in just a minute, but first we’re going to take a short break. Thanks for listening to Building Local Power. If you’re enjoying this conversation and want to hear even more about local solutions to big problems, I hope you’ll consider heading over to ILSR.org/donate to contribute today. We really do rely on your support to keep this podcast going, so any amount is sincerely appreciated. Now let’s go back to my conversation with Stacy Mitchell and Brad Lander of the New York City Council. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | We’ve talked a lot about housing, but how are these ideas potentially in play around commercial property? I mean, as you know, local businesses have not only struggled a lot in the pandemic, but even before that with rising rents and just all of the problems of maintaining space that’s suitable for what they need to do and also affordable. |

| Brad Lander: | Absolutely. So let’s start with the neighborhood retail sort of mom and pop businesses. And we need a lot of strategies here. I actually support some form of commercial rent regulation, so even in privately owned buildings, you know that your rent is going up at a stable amount each year. Sure, the cost of your owner experiences are going up, and you got to pay a little more because insurance costs or energy costs are higher, but you don’t just have to compete with somebody your landlord can bring in who might be able to pay twice your rent and throw you out. So that’s one piece. |

| Brad Lander: | But boy, when I worked at the Fifth Avenue Committee, we took over some abandoned property in the neighborhood that I live in. And it was affordable housing on the upper floors, but the ground floors had retail stores. And because we were a mission-driven non-profit with the goal of strengthening the neighborhood, we didn’t have to get the top, top dollar for every square foot of commercial space. |

| Brad Lander: | We had to make the project work to cover our financing, but that meant we could look to make sure the businesses were more likely to be owned by people of color, to be people from the neighborhood, not to be chain stores, somebody who had a neighborhood business idea, and then give them a long-term stable lease with reasonable rent increases over time so they could create businesses and stay there. |

| Brad Lander: | And really, that’s most of what I find, in our neighborhood, our retail, our small business startups need is just affordable long-term rent that is not going to spike and double, so they know they can make an investment, try something. Many succeed, many don’t, but that’s a fair way to give somebody a chance to start, is not to rip the rug out from under them because so many other spaces here, when a five year lease is up, you could pay double the rent, fine. |

| Brad Lander: | And if not, somebody else that is a bank that wants to come in or a new chain store that wants to come in, and local owners without a lot of capital, just even if they’ve got a good business, can’t possibly pay twice the rent they were paying. And that’s true for light manufacturing businesses, that’s true for arts-related businesses, folks who are doing work in the creative economy, and it’s certainly true for the mom and pops and retail stores in so many of our neighborhoods. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Just to rewind slightly to talk about something you mentioned earlier related to this. You are also involved with a program that is working with commercial landlords to renegotiate leases, right? |

| Brad Lander: | We’re trying. That’s a bill that we are pushing, and we are calling it small business recovery leases. Yeah. The evidence here, the data here is just really kind of stunning. The Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce did a couple of surveys asking small businesses in Brooklyn whether they were able to cover their rent. And as they did those surveys over time, 75 or 80% of businesses said they were not able to pay their rent in full. And how could they? The rent is the biggest single cost they have. If their workers aren’t working, they’re not paying them. Those folks may be on unemployment, or maybe they got some short period of time with PPP, the Payroll Protection Program that Congress set up and, knock wood, is going to be starting up again. |

| Brad Lander: | But a lot of them had a big period of time when they had no revenue coming in, or at most could use 25% of their space. But only fewer than a quarter of landlords made any rent concessions to the small businesses that were in their spaces, even though they weren’t possibly able to stay open and cover their costs. So the number of businesses who have back rent is just enormous, and we need some way of working that out. So we came up with a program designed to share that burden between the city, the commercial or the property owners, and the businesses themselves. |

| Brad Lander: | And the idea would be you would enter into a new lease. We call them small business recovery leases. They’d have to be at least 10 years long. They’d have to have affordable rent increases during that period. The landlord would have to agree to forgive some of the back rent, and then some of it could be rolled into that this new lease in a way that was mutually acceptable to them and their business. And then the city would come in and give a property tax break equivalent basically to about half of what the landlord was forgiving. |

| Brad Lander: | So piece of it, the small businesses are still going to have to come up with, over time, a piece of it. The landlord forgives and forgoes, and then a piece of it comes in the form of a 10 year property tax break. And we think that would be a way to give these small businesses a chance to get started again as the economy begins to open back up. I should say, we’d love to be able to build on that toward a broader system of commercial rent regulation, that basic idea that we have in New York City for housing. |

| Brad Lander: | About half of our rental housing stock is covered by rent regulation. And I know this is, around the country, not the typical experience, and it’s taken as sort of a weird New York City thing, but it’s such a simple idea. If you live in an apartment, you ought to be able to know that next year you might have to pay a little more than this year because the cost of the fuel went up or the cost of insurance went up. So your rent might go up two or three or four percent, but you can’t be kicked out, and someone’s not going to come in who can pay twice as much rent as you and boot you out of your building. |

| Brad Lander: | It’s such a simple, reasonable idea that you ought to know you can stay with a reasonable rent increase. And we have that for half our rental housing market, but we could have it not only for more of our rental housing market, but for commercial properties as well. It’s certainly reasonable to make sure owners can cover the cost of increased costs. |

| Brad Lander: | But if you allow them to have the speculative value of their property, whatever they could get if they kick you out and bring somebody else in as their benefit, it’s really hard to give stability to anybody, to residential tenants, families trying to raise kids, or to mom and pop businesses who are investing their life savings and getting something started, and just need enough basic stability to try to make it work. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Does New York City have the authority to implement commercial rent control and also the authority around… I mean, I thought your solution around this idea to deal with the lost rent from COVID to say, “Okay, the city’s going to step in on about a third of it, the business is going to eat a third, and the landlord’s going to eat a third.” That feels like, okay, that’s a solution that is going to be hard for everybody, but there’s some equity and sharing the burden of it. Can New York just do that? And if so, what’s the holdup, and how does the commercial rent control idea also play into that authority? |

| Brad Lander: | Yeah, I mean, as your listeners well know, unfortunately cities are often beholden to their states for almost anything they want to do. And that is in part true here. Even for those small business recovery leases, we need state permission to establish new tax incentives. We don’t have the power in New York City to grant this kind of tax incentive for small businesses. So I’m working with some state senators and assembly members to try to get authorizing legislation in Albany so we can then pass it here. |

| Brad Lander: | It’ll be from the city’s property taxes, but we need authorizing legislation in Albany even to do it, which is kind of one of the frustrating forms of preemption that local communities all over the country have. The commercial rent regulation is really a complex and interesting question. Our lawyers believe that we could pass a pretty strong commercial rent regulation bill at the local level. It wouldn’t reset on new leases. One beautiful thing about our residential program is that actually, it stays affordable even from one tenant to the next tenant. |

| Brad Lander: | You can’t go to market even when there’s a vacancy. That turns out to be important, because if you can go to market when there’s a vacancy, the incentive to harass and displace tenants is just overwhelming, as we saw in New York City through some loopholes in our laws. On the commercial side, I think there would have to be a ,ark to market at new leases, but we think we can do it for the period of time that a lease would be covered. We’re working on a bunch of the legal questions, but the reason why we don’t have it even though we could do it, you know the answer to. I mean, real estate has a lot of power in New York City. |

| Brad Lander: | That’s true in all kinds of times, but it’s certainly true at a moment like now. There’s this anxiety that people are leaving the city. Will they come back? Can we make more demands? And to me it’s less about what you can or can’t demand and more, what’s the model of solidarity and shared sacrifice that you’re trying to build a city going forward on? You know better than anyone at just how much money and how much more value Amazon and the delivery companies have had. |

| Brad Lander: | I just saw something that fast food employers are worth $40 billion collectively more than they were a year ago. So that’s what the pandemic is doing, is transferring wealth from kind of small businesses and communities to these mega corporations. And we’re going to have to be a little more courageous to do some things that set a better platform. I know in New York, we have people that will want to start up small businesses when we can open the economy, to save the ones they have, recapitalize them, lean forward, and also create some new ones. |

| Brad Lander: | But that’s going to work so much better if we could do it on a platform of stability and affordability and fairness, but we got to have the guts to change the rules, but that means building more political power than we have. I think that’s why our elections coming up are so critical. This is just an important moment for people, really. We all want to pull together, but we have to pull together with some bold new policies, not pull together imagining that the old rules will work differently than they have. And that’s why this moment calls for bold new politics. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | You’ve mentioned that there’s some components here that are unique to New York City, but I’m wondering if there’s certain things that you’re working on that you think other cities could learn from if leaders want to push for similar things in their communities? |

| Brad Lander: | Absolutely. First I’ll say, we’ve learned from a lot of places around the country. So I don’t want to do too much of the New York exceptionalism. I heard a great story recently from my friend, Greg Casar, who’s a city council member in Austin who helped a group of really very low-income Latino mobile home residents whose landlord was trying to boot them out all together to I think sell the property for condo development. And they were able with the support of the city council, not only to prevent that sale, but to buy the property, to buy the mobile home property from the owner and convert it into a cooperative mobile home park. |

| Brad Lander: | So there are examples all over the country of people using this model of social ownership to do creative things. The community land trusts around the country that are best known are in Burlington and Albany and North Carolina. So there are some great models. I do think more people are going to have to look to or should look to multifamily limited and shared equity cooperative home ownership. That is not unique to New York. Some other places have it, but not a lot of places. |

| Brad Lander: | But if we want to make some forms of stable, affordable, durable home ownership available to a much wider range of people in the coming years, especially given the climate crisis, we know that building more suburban communities that you have to drive a car to get to way out in the exurbs is not a sustainable model, even if you could offer affordable ownership. But to the extent we’ve been able to make it possible for people to have affordable ownership, that’s what it is, is a small place at an exurb very far from your place of work with a long commute. That’s not a way that I think… It’s definitely not sustainable. |

| Brad Lander: | I don’t think it’s a way that people want to live, either. So investing more in cities, allowing multifamily housing, and using this model of co-ops with reasonable resale restrictions. So you make a little money, more than you would have if you had put that same amount in a savings account, but it’s still affordable to the next buyer. I think that people are doing that model of what we call limited equity cooperatives, or shared equity home ownership around the country on community land trusts and otherwise. I really hope that that is something that we can jumpstart all around the country with new resources from Washington. |

| Brad Lander: | Hopefully there’ll be more money for investment in affordable housing. And I hope we can use some of these new models to make sure it really has durable value. First, just that it stays a permanent public asset, that it’s not at risk of being lost when the owner sells it, whether that’s a private developer or the first homeowner. But it also builds that form of more democratic, collaborative ownership and decision-making that restores control to communities. And to me, that’s an appropriate response to the inequality and racial justice reckoning that we’re seeing in this moment. But I really do think it’s going to be important as well as we’re trying to prepare our cities for the climate future to make them more sustainable. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Yeah. There was a line or a question from your piece in the New York Times that was something like, “Who can imagine a future here, or can the average person imagine a future here, and what is that going to look like?” That, I think, is the big question. |

| Brad Lander: | I’ll encourage to your listeners to read this wonderful new book, Ministry for the Future, which is Kim Stanley Robinson’s new book. It’s a science fiction, or I guess there are some people that are calling it climate fiction, but it tries to imagine… And this one, actually, after some horrible things happen in the beginning, pivots in a positive direction, almost a utopian direction, but with climate realities in mind. And I think people will see these connections between what we have to do if we’re really going to confront the climate crisis with some of these models of local ownership and more permanently affordable and durable public value. |

| Brad Lander: | I found it really useful. It’s hard to imagine a future like that. We know the horrors that are coming. We know what an economy looks like that’s got more Amazon and McDonald’s, and it’s unfortunately, through some books, not hard to imagine what a planet ravaged by the climate crisis looks like, imagining something that we could live in, or our kids could live in, that lives by the principles of sustainability and equity. But it’s for real. It has to get loans and keep the roof from leaking, and invest in our communities. |

| Brad Lander: | It’s hard to do. And I think you and I are lucky to have seen some amazing examples in communities, but our challenge is to scale that up, not to have them be small boutique pilot programs, but to have them be what the federal money is supporting and measuring in the footprint of our cities, how much of that and a property is under various forms of social ownership. So I think it’s an exciting time, and I think it’s a platform for the creativity our people have. |

| Brad Lander: | But the politics of winning it are not utopia. The politics of winning it are through really hard organizing. And obviously when people are experiencing standing in food lines and experiencing the kind of suffering they are, it’s an extra leap to say, “Not only do we need relief, but we need to change the rules to build that more community-owned and sustainable future.” But it’s an urgent time to do it. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Thank you so much for joining us, Brad. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | This has been great. Thank you so much. |

| Brad Lander: | Really an honor to be with you. And please, keep up the good work, and I’ll keep listening. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Thank you for tuning in to this episode of the Building Local Power podcast from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. You can find links to what Stacy, Brad, and I discussed today by going to ILSR.org and clicking on the show page for this episode. That’s ILSR.org. While you’re there, you can sign up for one of our many newsletters and connect with us on social media. We hope you’ll take the opportunity to help us out with a gift that helps produce this very podcast and supports the research and resources we make available for free on our website. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Finally, we’d ask that you let us know how we’re doing with a rating or review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts. This show is produced by me, Jess Del Fiacco, and edited by Drew Birschbach. Our theme music is Funk Interlude by Dysfunkshunal. The Institute for Local Self-Reliance, I’m Jess Del Fiacco, and I hope you join us again in two weeks for the next episode of Building Local Power. |

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

If you have show ideas or comments, please email us at info@ilsr.org. Also, join the conversation by talking about #BuildingLocalPower on Twitter and Facebook!

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | RSS

Audio Credit: Funk Interlude by Dysfunction_AL Ft: Fourstones – Scomber (Bonus Track). Copyright 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and, for monthly updates on our work, sign-up for our ILSR general newsletter.