Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download | Embed Subscribe: RSS

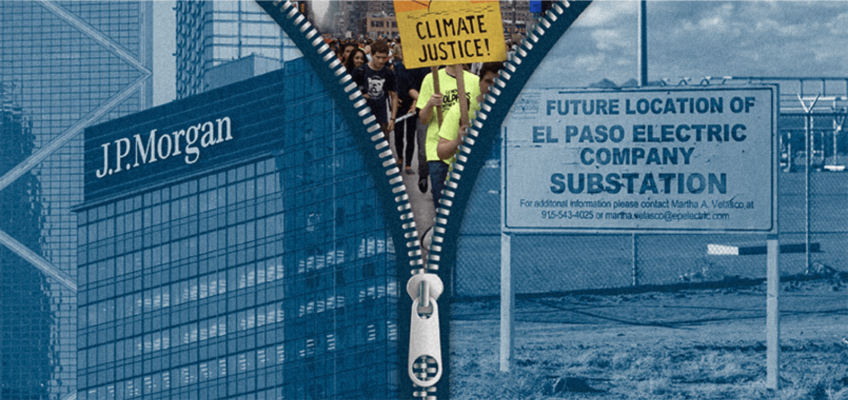

The Permian Basin, the largest producing oil field in the United States, is located in Texas. JP Morgan is a major shareholder of the Permian Basin and in 2019, through its affiliate, Infrastructure Investment Fund (IIF), successfully acquired the El Paso Electric utility company. The utility is responsible for powering the city and operates three significant gas plants that convert fracked gas into electricity, and JP Morgan saw the acquisition of El Paso Electric as a lucrative opportunity to amplify their profits from the oil and gas industry.

Amanacer People’s Project saw it differently. They saw the proposed acquisition of El Paso Electric as a direct threat to climate justice. Despite unsuccessfully blocking the acquisition, Miguel Escoto from Amanacer is optimistic about the region’s prospects for transitioning to democratic control over our energy grid.

Amanacer People’s Project: Amanecer People’s Project is a community advocacy and power building organization that aims to shift decision making power away from polluting elites and place it back in the hands of the community. Our goals as an organization are clean air, clean water, and community control of our resources.

Oilfield Witness: We are methane hunters. We use optical gas imaging technology to expose the dirty secrets of oil and gas. We leverage this intelligence to educate the public and policy makers to strengthen climate movements.

“Direct Democracy Climate Radio” podcast on El Paso: Three Part Educational Podcast on the Origin and Theory Behind the “El Paso Climate Charter”

“Murdering Our Stars” podcast on Texas oilfields: The Permian Basin is one of the worst climate polluting oil and gas basins in the world. Your host Miguel Escoto and certified thermographer Sharon Wilson take you on an in-depth tour of this climate bomb. In this special 8-part series podcast — through conversations with whistleblowers, thermographers, impacted community members, former oil workers and other experts — you’ll get up close and personal with this global threat brewing in Texas. A phenomenon so powerful, it murders stars.

Fatal Vapors: How Texas Oil & Gas Regulators Cause Avoidable Deaths: Report on sour gas lack of permitting.

Texas Agency Fails to Enforce Poison Gas Laws: Report on flaring lack of permitting.

Book:

A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal by Kate Aronoff, Thea Riofrancos, Alyssa Battistoni, Daniel Aldana Cohen

| Reggie: | Hello and welcome back to another episode of Building Local Power. I am your co-host, Reggie Rucker, and we’re continuing this season of How to Get Away With Merger by keeping with the conversation on corporate consolidation in the energy sector. Our last episode featured the story of a coalition able to block a bid from a multinational energy firm to buy the dominant local energy provider. Today’s story might not have quite as happy of an ending, but our guests will make as hopeful as ever. So hopeful in fact, we’re going to focus the full episode on just his story and how it intersects with the merger. To get into it, let me toss it over to my co-host, who I am very excited to play cribbage with later this week for the very first time. Luke Gannon. What’s up Luke? |

| Luke: | Oh man, I am so excited to play cribbage. It’s really the perfect time of year for it and it’s also a perfect time of year for this episode, which so well details one of the biggest issues we face today, environmental destruction. Our guest on the show today both lays out where we are now, but also as we head into the new year, a path forward. Our guest today, Miguel Escoto, is one of the founders of Sunrise El Paso, which is now transitioning to Amanecer People’s Project, which is a community-led climate justice organization in El Paso, Texas that advocates, organizes and builds power around clean air, clean water, and democratic control. Miguel is also the organizing director of Oil Field Witness, where alongside his colleague Sharon Wilson, visits oil and gas shales to document emissions and share with the public and elected officials to support climate justice movements. But let’s start from the beginning. Here’s Miguel. |

| Miguel: | My name is Miguel Escoto. I was born and raised here in El Paso, Texas, in the Borderland, both sides of the border. This is my hometown, my home community. Like many people here in the border, like many Fronterizos, I have deep ties to both sides of the border. A lot of my family is from Mexico, still there in Ciudad Juarez. Most of my childhood was in Ciudad Juarez. My parents and I would cross the border every morning very early so I could have an education in the US. And so that’s a pretty common experience here. Very, very porous and rich interconnected cultures. |

| I moved from Juarez to El Paso permanently in around 2007 because of the increased violence from the drug war. And that was very impactful for me because I understood the privilege I had in being able to cross the border to flee for safety, essentially. And that is what led me to my first organizing experience in the world of immigration justice. I helped fundraise for two local immigration advocacy organizations here in El Paso, Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center and migrant service clinic run by the Catholic church here. So that was my first introduction into activism and organizing was through the issue of migrant justice. | |

| But eventually I understood how the climate crisis was connected to the immigration justice issue because I would witness and learn and read about how a lot of what drives immigration and refugees in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, is an increased change in climate, right? Rising sea levels, hotter climates, increased floods is what is leading to a lot of climate refugees. So I sort of turned my focus to immigration to climate justice, and that led me to understand how El Paso in West Texas plays a very important factor in the global climate crisis because of the Texas oil fields, especially the Permian Basin, which is a huge, huge part of the global problem of climate change. | |

| Luke: | Texas is at the epicenter of the global climate crisis, but Miguel and the Amanecer People’s Project view it as a promising opportunity to demonstrate the potential of transitioning to green energy. Let’s dive into the interview. Can you tell us a little bit about what the energy industry looks like in Texas? Who are the big players? How much of the market do they control? |

| Miguel: | So unfortunately, oil and gas reigns in Texas. Texas has some of the worst oil and gas shales in the world. One of them is the Permian Basin, which is in west Texas and southeast New Mexico. The Permian is the number one source of climate emissions on the planet according to data from Climate TRACE Map. It produces an extreme amount of oil and gas every day. Currently, the Permian is producing more than 5 million barrels of oil per day, and that number is expected to increase to 10 million barrels of oil per day by 2030. This is just contradictory to every scientific recommendation regarding fixing the climate crisis. The science is telling us that we need to stop production, stop drilling new wells, stop new fracking, but the exact opposite is happening in the Permian and in Texas in general. There’s also the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas, which is producing over 1 million barrels of oil per day. |

| So it’s like the evil little brother of the Permian Basin is the Eagle Ford. There’s also the Barnett Shale, the Haynesville Shale. So overall there are more than 275,000 active oil and gas wells in Texas, and there is just an extreme amount of production, which is a problem because of the current era of climate crisis that we’re living in. It’s also a problem that the state government overwhelmingly protects fossil fuel profits at the expense of the health of Texans and the environment as a whole. The Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates oil and gas, not railroads, aim to inspect facilities once every five years, so that is woefully inadequate. That means there’s only one inspector for every 1,600 oil and gas facilities. That’s just unmanageable. It’s effectively unregulated in the Permian. There’s also flaring, which is a process related to oil and gas production, which is largely inevitable by the oil and gas industry, but this is where excess gas needs to exit the production system. | |

| And in the process is, the process of flaring combusts this gas so that it emits less, but generally flaring is also unpermitted and unmanaged by the Texas regulatory system. A study by Earthworks, which was done by Jack McDonald and Sharon Wilson, demonstrates that 69 to 84% of flares do not have the necessary permits in order for them to flare. So it’s going largely unregulated and unknown by the industry. There’s a big emergency here in Texas in that we have an extreme amount of production and we have a government that refuses to regulate the industry to protect its residents, its workers and the environment. | |

| Reggie: | Okay, so having laid that out, can you sort of provide us the context for where El Paso Electric fits into the industry and in doing so, help us to understand why Infrastructure Investment Fund, which is associated with JP Morgan Chase, why they were interested in acquiring El Paso Electric. |

| Miguel: | El Paso is in far west Texas. It is a couple of hours drive from the Permian Basin, and it is economically and culturally connected to this oil field. Culturally, it’s connected because a lot of the oil and gas workers that are extracting oil and gas in the Permian are from El Paso or grew up here, are working the fields because that is what is economically available in this community. It is economically also connected because the utility that runs the El Paso service area, El Paso Electric, is physically hooked up to the Permian Basin. So El Paso is the 10th sunniest city in the entire world, and it only uses 5% renewable energy in its grid, which is a big squandered opportunity that has a very clear explanation. El Paso Electric utility is an anomaly, and even in Texas it is both a monopoly and a privatized company. So in other cities in Texas, it’s either one or the other. |

| This means that El Paso Electric as a private company that has a monopoly over its customer base as a incentive to cut business deals with the fossil fuel industry right on their doorstep, including the largest and most active oil and gas well, oil and gas shale in the world, right? That is why even before infrastructure investment funder JP Morgan got involved, El Paso Electric was hooked up to the Permian. They run three major gas plants, Newman, Montana Vista and Rio Grande that power the city by receiving fracked gas from the Permian and converting it into electricity. | |

| This is a process that emits a lot of pollution to the climate like CO2, but also emissions that hurt and harm our respiratory health, like particulate matter, volatile organic compounds, and that’s why El Paso is the 13th worst polluted city in the country when it comes to ozone and why a lot of this community has asthma. So this horrible hellscape of fossil fuel production and pollution is what attracted JP Morgan Chase. In 2019, they started their lobbying to have the city government approve their acquisition of El Paso Electric. JP Morgan Chase is one of the largest shareholders and profiteers of the Permian base in oil and gas shale. They directly invest in drilling companies such as Diamondback Energy. JP Morgan is currently the seventh-largest investor of this company, just as an example. | |

| So they are profiting from the production of oil and gas, and they wanted to profit from the consumption of this gas directly in a utility scale, oil and gas and Permian Basin, not withstanding, El Paso Electric is a very profitable business. They have a revenue of around $800 million, gross profits of upwards of $353 million per year because they have a very sweet deal of being privatized and having a monopoly, which is a problem when it comes to what should be a public good, like electricity, the way roads, schools, fire departments, education should be a public good, electricity should also be a public good. But we have this very oppressive system here in El Paso where a private company has control over it. This is what really attracted JP Morgan to buy out El Paso Electric. | |

| Luke: | In 2019, you said that JP Morgan and Infrastructure Investment Fund started lobbying. Can you talk a little bit about what that lobbying looked like and then get into the public response to it, the opposition to it, and how that played out? |

| Miguel: | JP Morgan Chase representatives and lobbyists and lobbyists from Infrastructure Investment Fund, they ran a full campaign to convince the city council, the elected representatives of the municipal government to approve the merger. It was something that was ultimately in the hands of elected officials. Their first tactic was to lie to the elected officials and to the public by saying fundamental myths, lies. One of them was that Infrastructure Investment Fund had no connection to JP Morgan Chase, that they weren’t owned by JP Morgan. This was something that has been disproven thoroughly, even at a federal level now with the research hard work of Tyson Slocum, for example. The second one was to convince the unelected bureaucrats in the municipal governments, including the city manager and the city attorney, that in fact El Paso had no say over this. They tried to convince the elected officials that this was not up to them. |

| This is just something that is going to happen between two corporations, the government should not be involved. Which is, again, a lie because they needed a vote by city council in order for this to go through. So Sunrise El Paso led a organized resistance to prevent this, and this included going to city council meetings to pressure our elected officials. We would stage direct actions. We held community meetings to inform the public about what was happening, and we created a pretty powerful movement that led to this being a discussion at least. And so ultimately, unfortunately, the city council did vote in favor of this buyout five to four. So it was a very close fight. We at least pulled back the veil, pulled back the curtain to educate a lot of the public about what was happening and why our electric grid is something that belongs to us, should belong to us instead of private corporations connected to fossil fuel production and pollution in the Permian Basin. | |

| Reggie: | This is my first time hearing of a merger that could be stopped by a city council. Is there something that unique about the way that Texas utilities operate, where there is that local government say in whether or not this merger can happen? Can you explain that a little bit more? |

| Miguel: | This is a very special case because under the franchise agreement that allowed the utility to be privatized and monopolized, there was part of that contract was to give city council some sort of say when something this big happened. And unfortunately in this incredible moment of leverage, the city refused to negotiate against the utility to give us more guaranteed rate reductions or have them commit to more renewable energy, et cetera. But that incident taught us that within the city government, there is a lot of protectionism and defending of El Paso Electric. That’s not how government should work. The government is not meant to serve the interests of a private company at the expense of the public. It should be the other way around. |

| Reggie: | Absolutely. Absolutely. Acquisition only happened a few years ago, so maybe it’s too early to tell, but are there ways in which you’re already starting to see this acquisition play out, presumably to the detriment of El Paso residents and the community there? |

| Miguel: | Very shortly after the buyout was approved, our nightmares and our fears were made reality. Right during the campaign, we kept warning that if JP Morgan had control over the utility, they would only further their commitment to fossil fuel production instead of renewables. And that is a thousand percent what happened. Only months after the buyout, the utility announced the permit application for the project known as Newman 6. This would be adding a massive 228 megawatt turbine to the existing Newman generating station. This gas plant is located in Northeast El Paso and very near a marginalized, largely Spanish-speaking immigration, mixed status, low income community chaparral. |

| And so very shortly after the buyout, we knew that they were doubling down on their commitment to fossil fuels. This project that they wanted permits for would cost the El Paso electric rate payer $163 million. It would massively increase pollution. For example, it would bring the station’s CO2 emissions to 1.3 million tons per year, which is again unacceptable in this era of climate crisis. So Sunrise El Paso, Amanecer People’s Project strongly and passionately fought against this permit as well. We organized to pressure our state and municipal elected officials to reject this. We eventually organized alongside with the frontline community members of chaparral. We were able to challenge the permit at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, and we won enough leverage to get some concessions from El Paso Electric. The state government regulatory system is not designed to prevent fossil fuel companies from getting their permits like this, but it did. | |

| It was a victory in the sense that we won a lot of concessions because of our fight. We won a legal commitment to never expand that specific gas plant ever again. We won a four-year moratorium on any new fossil fuel projects. This is very important because El Paso Electric was already planning on a Newman 7 and a Newman 8. They just wanted to continue building out more gas instead of renewables, and we won a 40% reduction of CO2 emissions and ozone forming nitrous oxide pollution. So we reduced the pollution 40% than otherwise would’ve been occurring, and that was an important fight for us. But unfortunately, their own business plans demonstrate that they still want to add more megawatt production and fossil fuel capacity into the future and decades to come. For example, they’re planning a 88 megawatt gas fired generation in 2032. They want to add another gas fired unit of 52 megawatts in 2034. | |

| They want to add another 80 megawatt unit in 2038 and another 54 megawatt combustion turbine in 2040. So this is just unacceptable. It is unacceptable for them to do this. It is a attack on our climate. It is an attack on our lungs, and it is something that at Amanecer People’s project, we will work very hard. We will build enough power to prevent this from happening. These turbines, they are designed to last 40 years, and if we continue to build more fossil fuels, it is game over for the planet and for humanity. So we’re not going to allow that to happen. | |

| Luke: | I know the fighting process is so much of the battle and it can be hard spending time dreaming, but what would El Paso’s energy future look like if it was up to Amanecer People’s Project? |

| Miguel: | Our main message and main goals are clean water, clean air, and democratic power over our resources, including our electric grid. Our vision is for our electricity to be something that’s run as a public good instead of a private profit. And we want to build enough power to where our electric grid works for us instead of JP Morgan shareholders. And the positive aspect, the great silver lining, is that there is wild solar potential in Texas, especially here in the southwest. Like I said, we’re the 10th sunniest city in the planet and we only have 5% renewable energy. We could turn that around in a matter of a couple of years. We could experience and win a massive boom of solar production, renewable production, and clean energy and green jobs, right? This would ultimately be a massive job creator in our region. So that’s our vision that, it’s not economic prosperity at the expense of environmental health. They’re actually the same destiny. We can win both a clean, renewable future and an economy that works for the 99% of us. |

| Luke: | Before we jump into our final book question, I wanted to follow up with some additional information Miguel sent me. Just last month, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission came out about the ties between Infrastructure Investment Fund and JP Morgan. A public comment letter to the Federal Reserve stated that this relationship, quote, undermines any potential for independence between the two entities. At least for El Paso, this was a little too late. Find out more about this in the show notes. All right, back to the interview. |

| Reggie: | Is there a book that you would recommend to the listeners so that they could dive deeper into the issue and get a better sense of what you all are working on? |

| Miguel: | One really good book that I recommend is A Planet to Win, Why We Need a Green New Deal by Kate Aronoff and other journalists and scholars. They provide a really good analysis for how we can transition to renewable energy in a way that supports the economy of the 99%. And they specifically talk about energy democracy. They bring up the notorious PG&E in California. But this is a great analysis that hasn’t informed a lot of what we do here in El Paso. And as of yet, we don’t have books written about what we do here in El Paso but we do have a few podcast series that we’ve produced to share our story. |

| One of them is a three-part podcast series that is called, Direct Climate Democracy Radio. Direct Climate Democracy Radio, it tells the story of how we fought the JP Morgan buyout, how we fought the Newman 6 gas plant, and how that led to the creation of a ballot initiative called the El Paso Climate Charter, which was a climate action plan for the local city governments to take bold action against the utility to begin the process of transitioning the utility to public ownership. | |

| That podcast series as well as another eight part podcast series on Texas oil fields called, Murdering Our Stars. And that’s again, a deep dive into Texas oil fields, the situation in the Permian Basin when it comes to radioactive waste, climate pollution, oil and gas worker, dangers on the job, et cetera. Those would be my recommendations. Thank you all for covering this. | |

| Reggie: | What a great story. Thank you, Miguel. And thanks to all of you for listening all the way to the end. I assume that means you like this episode, so please share with even just one person you think will enjoy it too. We have a goal of 10,000 listens for this episode, so help us get there. And if you’re not a subscriber to the podcast yet, make sure to hit that subscribe button so you know when every new episode drops. And of course, your donations are essential to help us keep this podcast going and support the research and resources that we make available on our website for free. |

| We truly welcome and appreciate it all. And last, if you have feedback for us or want to share a story about how your community approaches this issue, send us an email to buildinglocalpower@ilsr.org. We’d love to share these on a special mail back episode one day. We’ll definitely keep an eye out. This show is produced by Luke Gannon and me, Reggie Rucker. This podcast is edited by Luke Gannon and Andrew Frank. The music for this season is also composed by Andrew Frank. Thank you so much for listening to Building Local Power. |

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by sharing Building Local Power with your family and friends. We would love your feedback. Please email buildinglocalpower@ilsr.org. Subscribe on the podcast platform of your choice.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | RSS

Music Credit: Andrew Frank

Photo Credit: Em McPhie, ILSR’s Digital Communications Manager

Podcast produced by Reggie Rucker and Luke Gannon

Podcast edited by Luke Gannon and Andrew Frank

Copyright 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license.

Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and, for monthly updates on our work, sign-up for our ILSR general newsletter.