Forty-three years ago a merry band of three launched the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. We self-consciously did so on May 1st, a date historically associated with popular rebellions against states, church, corporate bosses and cultural norms.

Mayday arose thousands of years ago as a celebration of the end of winter.

Mayday was one of the most popular feast days for medieval craft guilds, a raucous and fun day during which a Queen of the May was elected and young single men and women danced around the Maypole, holding on to ribbons until they became entwined with, potentially, their new love.

The Church feared the freedom Provided by the May Games for men and women to mingle, drink and dance together provided.

Mayday was a celebration of the common people. One its the central figures was Robin Goodfellow – the Green Man – the Lord of Misrule for the day. It was a day when Robin and the villagers could make fun of Priests and Lords and local authorities.

Mayday was a celebration of the common people. One its the central figures was Robin Goodfellow – the Green Man – the Lord of Misrule for the day. It was a day when Robin and the villagers could make fun of Priests and Lords and local authorities.

Goodfellow also reflected the hunting traditions of the time. Most believe him a predecessor of Robin Hood, who by some versions became an outlaw after he hunted game on the King’s land.

One scholar describes the context for Robin’s popularity, “As the enforced enclosures of the common land and the superseding of old protective customs by new laws grew in pace, the newly destitute joined the droves of beggars and vagabonds who had always populated the countryside. It was possible for a bonded peasant or wage labourer to look with envy on those who dispensed with all social ties and responsibilities and lived in liberty in the forests.”

Another maintains, ‘For centuries Robin Hood was a symbol of independence, of resistance to authority in church or state.” In Tudor England Robin led the tremendously popular May Games. Ballads about him circulated widely, and still do.

Eventually the combined opposition of Church and State led to the banning of Mayday and the Maypole in the 1600s, although the tradition carried on in many rural areas and trade societies for another two hundred years.

In the 19th century, Mayday again became a symbol of rebellion. Before the Civil War a movement for an 8-hour day arose. The rank and file, often forced to work for 10, 12, 14 hours a day, enthusiastically embraced the movement despite indifference and even hostility of union leaders.

By 1868, the movement had succeeded in convincing Congress and 6 states to enact 8-hour legislation. But the laws were very spottily enforced. In 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Assemblies passed a resolution declaring that from May 1, 1886 on, a legal day’s workday would be 8 hours.

By April 1886, hundreds of thousands of workers had joined the fledgling Knights of Labor. Chicago was the center of the movement, where organizing was led primarily by the International Working Men’s Association (known as the First International).

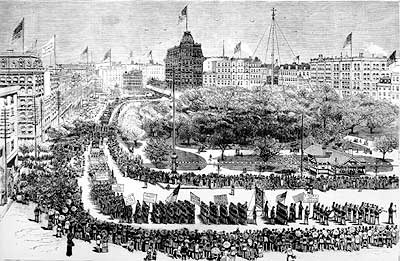

On the evening of May 1st, 50,000 workers already were on strike. The next day another 30,000 joined them. Most of Chicago’s manufacturing ground to a halt. By May 1st the movement had won gains for many Chicago clothing cutters, shoemakers and packinghouse workers.

On May 3rd police fired into a crowd of peaceful strikers outside the McCormick Reaper Works Factory, killing four and wounding dozens. A group of anarchists, led by August Spies and Albert Parsons, called on workers to arm themselves and gather in a mass protest at Haymarket Square the following evening.

The meeting took place and proceeded without incident. By the time the last speaker was on the platform the crowd had largely dispersed on that rainy day.

Then 180 cops marched into the square and ordered the meeting to disperse. As the speaker climbed down from the platform, a bomb was thrown at the police, killing one and injuring 70. Police responded by firing into the crowd, killing one worker and injuring many others.

Both press and church insisted the bomb was the work of socialists and anarchists. Business leaders viewed it was a good opportunity to rid the city of radical labor leaders and strike a national blow against the increasingly self-confident labor movement.

Police raided union offices and private homes. All known socialists and anarchists were arrested. Eight of Chicago’s most active anarchists were charged as accessories to murder.

Six weeks later a quickly convened court even more quickly convicted the 8, despite no evidence connecting them to the bomb throwing. Indeed, only one was even present at the meeting, and he was on the speaker’s platform.

They were sentenced to death. Four, including Albert Parsons, were hanged November 11, 1887.

Almost 250,000 people lined Chicago’s street during Parson’s funeral procession.

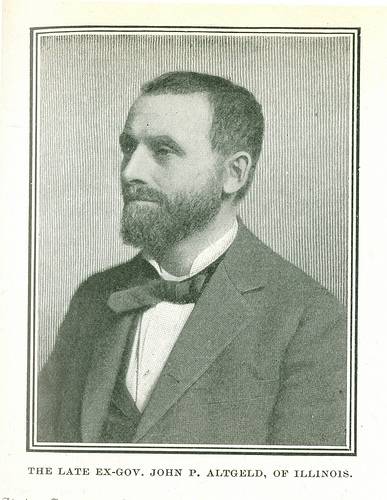

A powerful campaign to free three other imprisoned anarchists arose and ultimately found a sympathetic ear in Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld who in 1892 had led to a Democratic sweep of state offices for the first time in 40 years. He was leader of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party.

A powerful campaign to free three other imprisoned anarchists arose and ultimately found a sympathetic ear in Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld who in 1892 had led to a Democratic sweep of state offices for the first time in 40 years. He was leader of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party.

On June 26, 1893, Altgeld pardoned the prisoners, informing the country that they and the hanged men had been victims of “hysteria, packed juries and a biased judge.” Slightly more than a month before he signed the pardons, Altgeld explained to graduating seniors at the University of Illinois, “Wherever there is wrong; point it out to all the world, and you can trust the people to right it; wrongs thrive in secrecy and darkness.”

It was a profoundly courageous move, especially for a very ambitious and rapidly rising politician. Informed of the pardons, the Democratic Secretary of State complained of the possible effect on the party’s fortunes. Altgeld replied, No man has the right to allow his ambition to stand in the way of the performance of a simple act of justice.”

Before the pardons Altgeld had told Clarence Darrow, who was pressing him for the pardons, arguing they would be popularly received. “If I conclude to pardon those men it will not meet with the approval that you expect; let me tell you that from that day I will be a dead man politically.”

He was right. In 1896, Democrats were swept from office. Altgeld’s political career was over.

In 1889 in Paris the Founding Congress of the Second International declared May 1st an international working class holiday in commemoration of the Haymarket martyrs and the red flag became the symbol of the blood of working class leaders.

To this day, Mayday is a celebration of workers’ struggles in many countries. In the United States, though, it remains contested.

In 1921 Mayday was celebrated as Americanization Day, a response to the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and growing radicalism of a swelling U.S. labor movement.

In 1947, amidst the beginnings of anti-communist hysteria, the U.S. Veterans of Foreign Wars renamed May 1st as Loyalty Day. In 1958, after a decade of anti-communist fervor had led to a sustained nationwide hunt for suspected subversives that cost countless progressives their jobs, and prompted a law requiring job seekers to take a loyalty oath, Congress made it official.

The Lord of Misrule undoubtedly would have had much to say about that.

Sign-up for our monthly Public Good Newsletter and follow ILSR on Twitter and Facebook.