Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Welcome to the first episode of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s newest podcast series, “Building Local Power.”

In our first episode, Chris Mitchell, the director of our Community Broadband Networks initiative, interviews Olivia LaVecchiaa, a research associate with our Community-Scaled Economy initiative, about her work on the “dark store” strategy that big-box retailers have been using to slash their property tax assessments.

“A lot of our systems are set up to privilege big-box stores and these bigger companies,” says LaVecchiaa. “There’s this narrative out there that locally owned businesses can’t compete, when really that’s not what’s going on. They’re competing pretty well considering they have to swim upstream a lot of the time.”

For more information, take a look at our article on the tactic, “For Cities, Big-Box Stores Are Becoming Even More of a Terrible Deal.”

| Olivia LaVecchia: | They’ve been arguing that because the resale value of the stores are low that cities and towns should value even brand-new stores as though they’re closed, and that’s the dark store behind the name of this tactic. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Olivia, let’s talk about building local power. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | That is a lot of the work that we’re doing here at ILSR. |

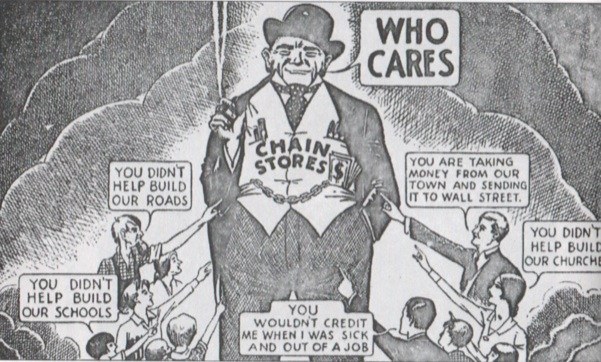

| Chris Mitchell: | I think this would be a great opportunity to talk about one specific instance of local power which has to do with having a good, strong tax base and making sure that businesses are paying their fair sure, making sure that the big businesses are paying the same as the smaller businesses and we don’t have government putting the thumb on the scale. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | Often it doesn’t work out that way. It’s these big companies that are able to find tax loopholes, have a lot of lawyers get out of measures like that, and they end up shifting the tax burden onto other companies that then have to work even harder to compete. |

| Chris Mitchell: | We’re going to talk about that in this first episode of Building Local Power, but just for people’s background, I’m Chris Mitchell. I run our work on internet access networks and helping communities to make sure they have that high quality internet access. Olivia, tell us a little bit about yourself. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | I am Olivia LaVecchia, and I work on our community-scaled economy initiative where we challenge the concentrated power of big retail chains and also look at policy measures that lift up locally-owned, independent businesses. |

| Chris Mitchell: | We’re representing just two parts of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. This series, Building Local Power, will be interviewing people from all different angles within the Institute for Local Self-Reliance and talking about hot topics and how we can make sure we have really strong communities. This is the first episode of Building Local Power. We’re going to talk about big box stores. We’re going to talk about this dark store ordinance. What is the concern with big box stores? Why do we not view them as being as useful for a local economy as the local businesses? |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | First, it’s just really true about ways that a lot of our systems are set up to privilege big box stores and these bigger companies, and there’s this narrative out there that locally-owned businesses can’t compete when, really, that’s not what’s going on. It’s that they’re competing pretty well considering that they have to swim upstream a lot of the time when things like tax incentives, banking structures, a lot of this structural stuff in our system is really working to stack the deck against them, just to mix my metaphors there. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Why should we be concerned if we lose all of our local businesses? |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | One of the things is just that big box stores are really expensive for communities. They cost them a lot in services like police forces, infrastructure like new roads, and often, actually, studies have found they cost more to service than they pay in taxes, so they’re a net drain on municipal budgets. That’s just some of the barebones numbers stuff. |

| Chris Mitchell: | I think this brings us to just one of these instances, and, in fact, you open up an article you wrote about what we’re going to call this dark store ordinance or dark store approaches, talking about how a local library got screwed and had to close down one day of the week because of the loss of tax revenue from a big box store, which was no longer paying its fair share. What is a dark star ordinance? |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | Actually, they’re not ordinances that cities and towns are passing. If there were direct policy around this, I think it would be a lot better. It’s actually this tactic that a number of different big box chains have been using in towns, counties, states around the country, and they’re bringing claims to state tax tribunals, arguing that their property taxes are too high and, in fact, winning judgments that are reducing their property tax assessments by as much as half. Property taxes are the leading source of revenue for all of our public services, and the effects have been really devastating. |

| Chris Mitchell: | That’s key point number one, I think, is that you have these very large stores which are, basically, cutting in half the revenue that they’re reimbursing local governments while local governments are paying so much to build roads to them, water systems to them, provide police to them. There’s been recent stories in the news about how the police are called every day to Walmarts in every community; it’s incredible. These communities that are the victim of this tactic, the communities are losing half of the revenue or more sometimes. Then, also, the thing that kills me is back revenue. They have to refund the previous year’s assessments in some cases, which is an incredible amount. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | You mentioned a story I wrote that opened with the library, and I’ll just use that as an example of what this can look like. That was in a township on the upper peninsula of Michigan, Marquette Township. That town really staked its economic development on attracting big box stores. It has a whole row of them on side of town. In 2008 a Lowe’s came in and built a $10 million store, and the local officials really celebrated it. The mayor was at the opening ceremony, all of that. Then less than two years later, Lowe’s went to tax court, and it argued that its valuation should be lower than the $5-some million that it had been assessed at. This brand-new store, and Lowe’s said it should be valued at $2.5 million in 2010, just $2 million in 2011, and down to $1.5 million in 2012, and Lowe’s won. |

| When that happened, I talked with the assessor for Marquette Township, and she was saying the township thought it had been a mistake at the time. It still had the building permits saying that this building was worth $10 million. As you were saying, it wasn’t just going forward; the tax judgment covered several years. Marquette had to refund three-quarters of a million dollars that had already been budgeted and spent, and, to do that, it had to shut down a day of service at the library. It had to cut other services, the school district, the fire department. It trickled up to the county, where the county had to close things like a youth home in order to save money. It was really brutal. | |

| Chris Mitchell: | This is a huge impact. This isn’t just a narrow, boring, who-cares tax policy. This is about whether or not your local government can provide essential services. How does this happen? How is it that they can just magically reduce the value of their store? |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | The reasoning behind it is really what drives home how outrageous what’s happening is. It ties into some of the fundamental issues with big box stores where the model for first-tier national chains like Lowe’s is to construct stores that are built to suit. When Lowe’s is ready for a new location, it builds one to meet its needs. When it’s ready to move, it’s usually cheaper to leave that store behind and build a new one. One example is Walmart rolled out a new format in 2007, decided to double its store size, and it left hundreds of vacant stores behind it around the country. Because of this model, it means that when big box stores come onto the market, it’s usually because they’ve already failed or been abandoned by the retailer that built them. |

| Chris Mitchell: | When you say, “Come onto the market,” you mean, if I’m just shopping for a big piece of land and I might see a vacant Walmart that used to be there, that’s what you mean. You’re coming onto the market. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | Exactly, right. |

| Chris Mitchell: | These big, empty stores, which I just think of them as being generally unusable for anything, although in the event of a natural disaster, I know FEMA will sometimes come in and use those. There’s not a lot of uses, and hopefully you don’t need FEMA to come into your community. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | We see them littering the landscape. A lot of the time they deteriorate into blight because the chain that built this store in the first place has left them behind, and not a lot of other people want them. Because that’s the real estate market that these stores are playing in, they’ve been arguing that, because the resale value of the stores are low, because they’re not worth very much, that cities and towns should value even brand-new stores as though they’re closed. That’s the dark store behind the name of this tactic. |

| Chris Mitchell: | I feel like this is like me telling the property assessor that because I’m going to cook crack in my basement my house should be valued less because it will probably burn down soon. That’s a decision that I’ve made, and I don’t feel like I should pay less taxes because I’ve made this very bad decision. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | The stores are deciding to build these stores that are really functionally obsolescent. |

| Chris Mitchell: | This is one of the things you cover. They actually restrict who can come in after them, and so they have this model that barely works. There’s very little value for these buildings, and then they say, “We’re going to artificially depress the value of this approach that we’re taking by then choosing that nobody else that might want to use it can use it because they would be a competitor to us.” |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | What you’re talking there is this thing that’s known as deed restrictions, where if you’re a Lowe’s, you put a restriction on the sale of the property that no one who moves in can sell the same things that Lowe’s sell. They don’t just mean a Menards or a Home Depot; they mean any store that sells rope or firewood. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Rope. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | The restrictions lower the value of the property even more. Lowe’s is coming in, putting deed restrictions on a property that it’s leaving behind so that a competitor can’t move in. By doing that, it’s participating in devaluing the property, and then it turns around and argues that its brand-new stores should be compared to that store. |

| Chris Mitchell: | It seems like one of those things that you might wish. I’ve often said that I wish that donuts would help me lose weight, and they don’t. I just don’t get to live in a reality in which I can eat donuts and lose weight, but somehow these companies get to do that. I guess, we’ll come to what local governments can do in a second, but I wanted to note first that the Michigan Chamber of Commerce says that you and local governments, you are vilifying some of Michigan’s largest job creators. I’m curious how you respond to that. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | The Michigan Chamber of Commerce has been defending these big box stores and this tactic that they’re using. The thing, I think, that is really often used as a straw man in arguments like this is that big box stores are large job creators. What isn’t acknowledged in that is that retail spending is generally a pretty fixed pie. If a new stores comes to town, people don’t suddenly have a lot more disposable to spend at that store. They just shift their spending around, and the spending that’s happening at big box stores and the jobs that are being created there, that’s coming from somewhere else. In a lot of cases, that’s coming from locally-owned retailers who, because they aren’t headquartered elsewhere, they also are using attorneys in town, management in town, printing services in town. They’re employing a lot more people than these big box stores are. It’s really something of a very misleading tactic by the chamber. |

| Chris Mitchell: | This is something that makes my blood boil because, presumably, the majority of people in the Michigan Chamber of Commerce are not big box stores, and they are the ones who have to big up the gap. If the big box stores are not paying their fair share, then all the other businesses … But this is where the chamber model can drive me nuts. You do more work with local chambers. I occasionally intersect with them in my work on internet access related things, and I find that there’s a number of chambers, particularly the larger chambers, the larger cities, the state chambers, certainly the national chamber, they tend to be interested in just what their biggest members are interested in, I feel like. We’re not going to get into this, but this is why we need local businesses to really not be supporting these organizations that are actually working against their interests in many cases. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | I think a lot of the time, just because national chains have wider brand recognition because they’re bigger, they’re in so many places, that translates into more pull, when, really, it’s locally-owned business that are doing a lot more. You touched on something there I just want to draw out, which is the shift in tax burden. When Lowe’s is cutting its property taxes by so much, services are cut, but also other property owners have to pick up some of that slack. In Indiana, county officials did a study that found that, if this kind of dark store valuation becomes the standard, big box retail owners will shift a tax burden of $120 million onto other kinds of taxpayers, in most cases, those who are less equipped to deal with it. |

| Chris Mitchell: | How prevalent is this tactic? |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | The first cases that we started hearing about came out of Michigan, and since then it’s spread to Indiana. It’s moved to Florida, Alabama, recently Texas. It’s one of the things about these big box retail chains. They’re national, and so they can test something in one location and then spread it very quickly. We’re talking tens of millions of dollars of impact that it’s having in all of these towns and counties. |

| Chris Mitchell: | What can a local government do, if you’re faced with a big box store that is suddenly saying, “Hey, we need to reevaluate how much taxes we’re paying”? I know some of the states have tried to deal with this. Maybe we can start there. What are states doing to try to help local governments in this case? |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | There are definite policy fixes to this, and some of them are simply just spelling out more directly in state laws how these stores should be valued, saying you should use this valuation method instead of this one. Then, from there, there are smaller escalating steps to take, such as saying the properties are comparing something to … can’t be properties that have had deed restrictions placed on them or can’t be properties that have been vacant for more than a year. Indiana is one of the states that has pursued some of these policy measures, although there some of these were passed in the 2015 legislative session, and even since then these big box stores have been winning some of their valuation battles. More needs to be done, but it’s a start. Then more broadly, it really gets at all levels of government. Economic development should focus more on growing locally-owned businesses than trying to attract and retain big box stores instead, which end up costing communities a lot more. |

| Chris Mitchell: | I think that’s really a key takeaway. That’s probably a good place to end the show, although we would be ending the show, if not for the final question, which is to just give me a good article or a good book you’ve read lately that you would recommend. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | I don’t know how interesting this answer is, but the honest answer is that the most recent book I read was Anna Karenina, which is a name that I definitely had heard before I read it. It turns out it was a totally fascinating story that drew me in. It has great passages describing pre-industrial farming methods where the main character’s just out scything in the field, and it’s mesmerizing. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Great. It’s one that I have to say I always have to choose. Am I going to like Anna Karenina more than three other books? Because that’s the choice, and so, I have to say, I’ve held off from some of the great historical works of literature because of that, but I’m going to have to get over that at some point. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | Sometimes they really are good stories. |

| Chris Mitchell: | Terrific. Thank you for discussing this with us and kicking off our new series of Building Local Power podcast. |

| Olivia LaVecchia: | It’s great to be here. |

| Lisa Gonzales: | That was Olivia LaVecchia talking with Chris Mitchell for our first episode of the Building Local Power podcast. Learn more about big box retailers’ strategy to cut their tax payments by reading Olivia’s article at ILSR.org titled, “For Cites, Big Box Stores Are Becoming Even More of a Terrible Deal.” If you’re a podcast fan, check out the Local Energy Rules podcast from John Farrell from our Democratic Energy Initiative and our Community Broadband Bits podcast from Christopher Mitchell. Thanks to [Dysfunction Al 00:16:16] for the music licensed under creative commons. The song is “Funk Interlude.” I’m Lisa Gonzales. Be sure to come back every two weeks for more interviews with the people at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Thanks again for listening to the Building Local Power podcast, and have a great day. |

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on iTunes or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

If you have show ideas or comments, please email us at info@ilsr.org. Also, join the conversation by talking about #BuildingLocalPower on Twitter and Facebook!

Subscribe: iTunes | Android | RSS

Audio Credit: Funk Interlude by Dysfunction_AL Ft: Fourstones – Scomber (Bonus Track). Copyright 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license.

Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and, for monthly updates on our work, sign-up for our ILSR general newsletter.