A Letter from ILSR’s Co-Directors: Remembering David Morris (1945-2025)

A message to friends and allies reflecting on David's visionary ideas, rigorous thinking, and lasting impact on movements for a just, sustainable, and democratic world.

Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download

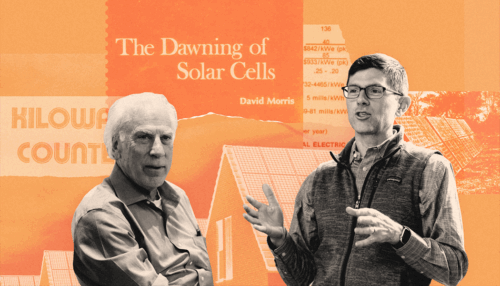

When ILSR co-founder David Morris published his pamphlet The Dawning of Solar Cells in 1975, nearly the only people using solar power were those in the Apollo program at NASA. Yet David saw decades into the future as he laid out a vision for community control and local ownership of a solar power system that was better for the climate and kept much more money in local economies than utility monopolies ever would. In many ways, says ILSR co-director and leader of the Energy Democracy Initiative, John Farrell, the world is still catching up with things David Morris wrote 50 years ago.

John Farrell“The unique thing that we have to offer is to help communities understand both what are the unique benefits you can get from clean energy, and how do you leverage the authority and power that you have as a community to do that.”

John Farrell is this week’s guest. To hear him tell it, one of the most important lessons he took from David Morris was that the idea of clean energy itself isn’t enough. In addition to the climate, we must also think about who owns energy and the systems that provide it. If clean energy systems are owned and controlled by energy monopolies, communities still find themselves at the mercy of huge corporations. A true energy revolution will come not only from clean energy, but community-owned clean energy. That’s the path to energy self-reliance. That’s the path that David Morris charted decades ago, and it’s the path that John Farrell and ILSR’s energy democracy team follow to this day.

Danny Caine

When Institute for Local Self-Reliance co-founder David Morris published his pamphlet, The Dawning of Solar Cells in 1975, pretty much the only people using solar power were the folks at NASA’s Apollo program. Hardly anyone on earth was using it, literally. Yet David saw decades into the future as he laid out a vision for community control and local ownership of a solar power system that was better for the climatevand kept much more money in local economies than utility monopolies ever would. In many ways, says ILSR co-director and leader of the Energy Democracy Initiative, John Farrell, the world is still catching up with things David Morris wrote 50 years ago. week on Building Local Power, we continue our remembrance of David Morris, who passed away in June.

Our guest is Farrell himself, who is working tirelessly to continue the energy democracy work that David Morris started with that pamphlet all those years ago. And our engaging conversation will cover David’s mentorship of John, state of the Energy Democracy Initiative today, and the obstacles and threats locally controlled solar power still has to overcome. Through it all, it will be clear yet again just how prescient David Morris was.

John Farrell, welcome to Building Local Power. So glad to have you on the show. I’m sure a lot of our listeners and followers of ILSR are familiar with the great work you’re doing with the Energy Democracy team, but they may not know the story of how you got to ILSR. And I’m sure David Morris played a large role in that story. So tell us you got to this work, how you got to this organization and what role David played in that whole story.

John Farrell

thanks for having me.

You know, it’s funny when he died, I, uh, kind of went back through and was looking in my personal email for sort of like, when was that first moment of connection between the two of us? I knew it was related to me getting hired. but I had kind of forgotten some of the details, which was I had just, I had finished graduate school at the university of Minnesota kind of earlier in that year. actually the year I got married.

And so I was looking around for a job and had a lot of different prospects was basically just calling up a bunch of people, doing informational interviews, getting coffee, you know, saying like, you know, what’s your organization, like whatever. And that was the context for how I contacted David. I said, you know, Hey, I’ve heard about ILSR or I’ve read about you on the internet. I saw your website, kind of interested in what kind of work that you do. what employees there do, how often you might be hiring. And his response to me was we have an open position, just come interview for it so I did.

So I met him and, and John Bailey, another long time ILSR staffer, and interviewed for this role, doing energy policy research. And it was really intriguing because it was about, the time ethanol was a big thing as like, you know, the major alternative fuel to gasoline and cars. And so was, but it was looking from this unique angle of farmer owned ethanol plants. The idea being that corn farmers are subject to commodity prices and the, you know, vagaries of the market and international trade, but owning an ethanol plant would give them a place to put these resources. So I was like, I don’t know anything about this, but this sounds kind of cool. And, know, I have a research background. I just got a master’s degree. I think I could do this stuff. So I interviewed it turned out David liked me and liked what I had to offer. So I got the job the very next week. He called me on Monday and was like, Hey, I’d to offer you a position.

And so it was very unexpected and very quick. I went from like one week thinking like, I’ve got 20 more names I need to go through on my list of people to call. And to all of a sudden being in the room with David and having this interview and not really having, honestly, a terribly good sense of what ILSR was all about at that point. I mean, I had read the website a little bit. knew what the name said, but I didn’t really know what it meant when I started working for ILSR.

Although nothing ever prepares anyone for working with David Morris. I mean, he just, knew so much. His depth of knowledge was so vast. The kinds of questions he could ask you were so pointed and insightful. And frankly, make you feel embarrassed sometimes that you were like, ⁓ here’s something that I thought I was well researched. He just poked 17 holes in it in a five minute conversation.

Danny Caine

That echoes things I’ve heard from other folks and kind of gathering stories and inspiration about David and his life. and now from starting, you know, almost blind, to helping to run the organization, however many years later, I spend a lot of time in the independent business corner of our world, but I’m really excited to talk to you and hear about what you’re working on, on the energy team. So I would love to hear specifically about some of the stuff you’re working on today, first and second, how David’s legacy is still impacting that work and how he’s still informing what you’re doing today with the Energy team.

John Farrell

I mean, think as a co-founder, there’s a degree to which David’s legacy and the legacy of the organization are very much intertwined. And I think about that often in terms of, we work a lot in partnership with organizations that care very deeply about climate change and the environment for the sake of those things.

And our perspective on energy is not that our perspective on energy is how does this enable communities to keep more of their energy dollars local? How does it enable greater decision-making about a community’s energy future? What are the technologies that allow people to have more decision-making power? So, you know, we have these interesting gaps between where other people might say like, ⁓ know, nuclear power is great because it’s, you know, low carbon when it generates electricity.

And we look at it and we say communities can’t own nuclear power plants. And in fact, know, the evidence suggests that it’s more cost effective to have clean energy anyway. So why don’t we find a way to make investments in wind and solar power that communities can own either at a community scale or on an individual scale. So that’s like a North star that David helped to impart to me through the work with him is.

We need to be thinking about energy from this unique perspective of local self-reliance. It’s right there in the name, right? And it’s a constant reminder to not get pulled into directions where it’s like, I’m just going to be a subsidiary of the Sierra club or the environmental defense fund caring about these issues because, you know, not that the reasons that they care about are unimportant from a climate change perspective, but reminding ourselves that the reason that we are here and that the unique thing that we have to offer is to help communities understand both what are the unique benefits you can get from clean energy and how do you leverage the authority and power that you have as a community to do that.

That’s the intersection point with the rest of our work too is so important. And I other part about David’s philosophy that I would say is important is, you know he really wanted our work to be based in good evidence. He didn’t want us to go out and say like, well, we should just build energy systems at a local level because he wanted us to show that actually there is a model for this to work that is financially competitive, that is economically beneficial, that, you know, really builds wealth in communities. And we, we found that and, know, and to find the examples of people who are doing that work. So not just like in theory, it would be great if a city does this, but to go out there and find the people who are doing the work to get to know them, to understand how they were successful and to share that story.

Danny Caine

We spend a lot of time on this show, it’s called building local power. We think about what exactly that means in all of our conversations here, local energy programs that keep all these money in the economy. It’s literally building local power. You mentioned like examples, who’s doing it well.

John Farrell

It’s a lot of different people in a lot of different ways. I’ll give just a few examples. So I work pretty closely with, a business in Minnesota called cooperative energy futures. I’m actually a small investor in the business. and it, model that they have is that they build community solar projects, but they’re a cooperative so that you’re not just a customer of them. When you sign up to be a participant in their community solar projects, where you get them, you know, a discount on your energy bill based on the electricity it produces. You’re a part owner of the co-op. You go to their annual meeting, you elect the board of directors, you help to give the direction for the co-op, which is largely oriented around how do we reach people who have traditionally not had access to clean energy and give them a chance to be an owner in the clean energy economy.

And I just think that organization really aligns so closely with ILSR’s values. I’ve interviewed their general manager about the projects that they’ve done. I’ve shared information with them to understand better, like what are the barriers that community-based organizations face in doing clean energy. And I really benefit from that relationship because they give me a sense of what is it like working in the trenches, navigating things like financing, tax incentives, finding customers, you know, working with municipalities to develop projects in partnership with public entities. that’s just one example. I remember doing an interview with the general manager at the New Hampshire Electric Cooperative. It’s an electric utility that serves largely rural community in New Hampshire. And they had what they called a transactive energy rate, which is essentially they were setting a price for which they would pay anybody who produced energy for them among all their customers.

So if you were a customer that could sell them solar energy, if you wanted to send them energy back out of your electric car battery, if you had some other thing on your property that you could use to send them energy back, they were basically figuring out, hey, how do we let our customers be what some people call prosumers, producing consumers? How do we work with them to meet the needs of our community as a utility? But instead of saying like, we’re the utility, we’re going to do all of it. They were asking their members, how can you help us do this work together?

So I just love finding stories like that of entities, you know, in this case, it’s a member owned entity, same with the cooperative energy futures. Sometimes we’re talking with public entities like cities, the city of Seattle and the city of Portland, both passed these fairly ambitious ballot initiatives to increase funding for the clean energy work that they want to do at a local level. And they did it through things like taxing large payrolls or taxing large retail businesses like big box stores, like Walmart and Target and whatnot, and pour that money into clean energy investment that would result in producing energy within the city’s boundaries in ways that would directly benefit their residents. So it’s stuff like that that just gives me the energy and the belief that there are so much opportunity that we can seize out there.

I think David really taught us that it was those kinds of examples that are the ones that we need to elevate those stories that we need to tell and those people that we need to talk to and understand how did they come about, how did they come up with those ideas and how did they make them work?

Danny Caine

It strikes me that you talk about the folks who are advocating for energy based on climate impact and then folks who are advocating based on economic impact in communities, but it’s not a both and. Like you can have both of these things. These systems are not only better for local economies, but they’re also better for the planet at the same time. It’s kind of a two birds with one stone situation.

John Farrell

Absolutely. On the reverse side, you can have things that are good for the climate and aren’t necessarily good for the community. You can have, your clean energy investment dominated by big corporations and utility companies and not see those broader economic benefits, the job creation in our communities, the wealth building opportunities. And so that’s kind of the lesson that I’ve learned too, is one of my jobs is not just to advocate for that for ourselves, but to try to educate our allies and say, Hey, if you incorporate more of this kind of wraparound economic benefits to communities, you’ll probably increase your political power in advocating for climate change because you’re getting people who do things for themselves, but then also see themselves in the policy.

A great example of this is I’m also on the board of a group called Solar United Neighbors and their philosophy, they have this beautiful little diagram. It’s help people go solar and then get them to organize for their solar rights and then pass policies that make it easier for more people to go solar. Like this virtuous cycle. And David used to talk to me about that all the time, that when you got more people to go solar, you were getting more solar users and you were getting more solar voters, even before that organization was founded. So I think David really saw that. And I think we’ve really seen that there is this opportunity to help people understand that the more we invite people to be participants, the more power we’ll have locally and collectively to see the change we want in the world around clean energy and climate.

Danny Caine

And of course, resources that John is mentioning will be linked in the show notes so you can have a look at them yourself. I think what you’re saying there brings me directly into my next question. And looking back at David’s legacy and work, it really seems like he was talking about a lot of this stuff long before other people. And I keep hearing again and again from people who knew him that he was really prescient in a lot of what he was thinking and writing about. So from your energy perspective, I think you can speak to this a lot better than I can. In what ways was he ahead of his time?

John Farrell

I mean, in all the ways?

The most concrete one is David published a paper in 1975 called The Dawning of Solar Cells in which he advocated for the federal government and state governments to invest in solar cell manufacturing to drive down the cost and make it more possible for people to do solar. And to get a sense of how prescient he was, the only place in the world we were using solar panels at that time was in the Apollo space program.

Nobody was building solar panels to be used anywhere else. And the first factory was set up actually not too far outside of Washington, DC around that time. And David was on it like immediately saying, this is the opportunity we’ve been waiting for. And this is the technology that allows us to democratize the use of energy and will allow communities to do more than they ever have been able to do before to localize energy production and to keep those energy dollars within the community.

And so he did an assessment as part of that paper at the city of Washington, DC, which is where ILSR was and was founded and showed that, you know, there was going to be real potential to keep so much more of that energy economy local if made huge investments in solar panels. And it’s exactly what played out. It just didn’t play out right then. People didn’t listen to David, unfortunately, in 1975, although the U.S. did have some of the earliest policies encouraging solar under Jimmy Carter that Ronald Reagan subsequently just demolished.

But it was some of those willingness to pay a premium price early and recognizing that that is what would drive down the cost of solar panels. what ended up happening was in the late 90s and early 2000s, that’s what Germany did. And then subsequently other countries did too with programs called feed-in tariffs. And the cost of solar fell like a hundred fold between the 1970s and today and tenfold even in the last decade because of that learning curve that we got in producing solar panels by incentivizing production.

Danny Caine

Has the world caught up to David? I feel remiss in not mentioning that in the one big beautiful bill act, there’s an end to some of these subsidies that make it easier for people to install home solar and democratize energy. So has the world caught up or do we still have things to learn from David’s work?

John Farrell

I don’t think we’ve caught sufficiently. I guess what I would say is at least, you know, ILSR has almost always focused on the United States. This is the place where we do our policy work. I’ve done some kind of international exchange learning, looked at, for example, Denmark, where there’s a lot more cooperative ownership of energy production.

in Germany where, like I mentioned before, those policies to encourage solar and local ownership were more, much more prevalent. one of the things that I think we have a tendency to do in the United States is we’re good at thinking about advancement of technology, but less good at thinking about the issues of scale and ownership, which is really what David I think was very prescient about.

You see that in the retrenchment sometimes on policy, you know, take California, for example, basically the leader in rooftop solar in the United States. And unfortunately, the folks who make the decisions about clean energy policy in California decided to roll back the programs to offer compensation for people doing rooftop solar, despite the evidence that suggests that it was a huge benefit to the state and to the local economy across the state of California. And as you mentioned, the one big ugly bill in Congress to more accurately describe its impacts, you know, they essentially said, despite the fact that we know that replacing dirty fossil fuel power generation with solar will have huge health benefits, climate benefits, environmental impacts, et cetera, et cetera, we’re no longer going to offer an incentive for that behavior.

First of all, just kind of ignores the basic idea of economics, which is you want to incentivize people to do things that are socially beneficial and you want to penalize things that are not socially beneficial and having tax credits for solar is a really powerful way and incentives for solar is a really powerful way to change behavior. And sadly, we had just with the Inflation Reduction Act, also taking David’s long time advice and restructured those incentives so they were more usable, but for people, even if they didn’t have big tax liability.

I mean, one of the problems we’ve had forever is if you give someone a tax credit, you have to have taxable income to use a tax credit, you basically already have to be rich. And what the Inflation Reduction Act did was it actually changed the way that we were able to provide incentives to make sure that it was more democratic in alignment with how the technology we’ve been seeing really exciting things happening in the past couple of years, or at least getting into the pipeline. So to see this get rolled back is really disappointing. And I think the lesson there in part is that, people were not focused enough potentially on the economic benefits of solar and especially that the small scale and local solar which I think would have provided a better defense than just it’s a clean energy technology that addresses climate change, which as we know has been turned into a political liability in many cases because of the success of the fossil fuel industry and their propaganda against clean energy.

Danny Caine

Well, our listeners can read David’s ever prescient thoughts from 1975 in the show notes that’s available as a PDF on the website. I really encourage you to take a look at it. It’s amazing. I never had the chance to meet David, unfortunately, even though I’m feeling his legacy kind of permeating everywhere and everyone at ILSR. But you were there like in Minneapolis. He was a real character in the Twin Cities and you were right there. So can you tell us some memories you have of just working with him that give us a sense of who he was and the passion he had for the work?

John Farrell

I mean, the first thing that comes to mind is he used to do what he called managing by walking around, which is to say that he would come to your office door and he’d say, what are you working on? And he would expect a really good answer. just to give you a sense of this too, like you’re probably in the middle of something, right? Maybe you’re processing an email, maybe you’re writing a memo, maybe you’re just, you’ve been like assembling seven different resources that you’re trying to put together. And he comes right into the middle of your workflow and is like, tell me what’s going on. So I do have to say, as I’ve learned about being a better manager over the years of being in that role, that I’m not sure that that was actually the best way to do people management, but it was definitely David’s way of doing it. And it was something that you had to be prepared for. I think it really reflected his notion that, I think this was an important part about how he was a good mentor, was that he was interested in asking you about what you’d learned and then asking you a bunch more questions to help you understand more deeply the issue that you were working on yourself.

So I might not have appreciated the manner in which those conversations happened, where he just popped up in my doorway. But one of the reasons that he was such an important asset to us at ILSR and, and I think a mentor to so many of us who came after him is that his way of imparting knowledge was by asking a lot of questions and encouraging us to go find the answers to them. And he would do by, as I said, walking around and poking his head in.

He was also just a consummate learner himself. He would often go out for lunch. He would, he would have a usual place, something I’m always a little envious of, like this idea that you go to somewhere so often that the people know your name, you know, the sort of the Cheers of, of the lunch hour. And, ⁓ he would bring with him 70 or a hundred pages of printed material to read during the lunch hour, every single time that he left. In fact, as we digitized so many things in the office.

We basically kept having a printer just for David so that he could print up stuff to take with him to lunch. Cause he didn’t like reading on a tablet or a laptop or whatever. He just wanted papers to take with him. But it was, mean, he was just so interested in understanding so deeply what we were working on so that we wouldn’t, you know, be caught in, our work wouldn’t be exposed in terms of having like a shallow understanding of an issue that we wouldn’t be so driven by mission that we ignored the actual evidence. And I think he taught the rest of us the same, that we have an obligation to really dig deeply when we’re doing research.

Danny Caine

You know, for better or for worse, managing by walking around has been a real casualty of the remote work era. No longer possible now that ILSR is fully remote. The only person walking around my house while I work is my son ⁓ during here in the summertime. And he’s not interested in what I’m working on if he’s popping in my door.

John Farrell

Yeah.

Danny Caine

This is really inspiring to me. I just love hearing about David and his impact on all of you. our listeners are also inspired, what do you think are some immediate things they can do in their community your perspective kind of his legacy and continue his work?

John Farrell

I mean, it’s just be a problem solver. Figure like if there’s something that bothers you about where you live or that you think could be better in your community, figure out how you can be part of that solution. Maybe it’s just you call your city council person, which, I live in a city of almost half a million people in Minneapolis and my city council person will still pick up the phone, will still respond to emails, local government folks or tend to be very responsive to people that talk to them. know, even in retirement in California, David was working in his community of Point Reyes Station, where the city was looking at, I think they had purchased an old public building and were turning it into affordable housing. And he was working on some of the zoning issues. He was working on the sort of intergovernmental issues.

You know, a tireless advocate for coming out there and saying like, Hey, we’re trying to solve a problem in our community. want more housing available for people to live here. And we can solve this as a community. Like we can do it publicly. council, our leadership, we have ways and tools that we can use, ⁓ in which we can solve these problems. he didn’t unfortunately write as much publicly about some of that work that he was doing, but to me, it was a real inspiration that entire life was sort of wrapped up in this idea that we can keep solving the problems ourselves.

And you see that to some degree in like the work that I do, you know, I’m still, I have for 10 years now been a member of this advisory committee to a clean energy partnership between the city of Minneapolis and its energy utilities. And there’s no question that that is obviously very work related for me. You know, I lead the Energy Democracy Initiative. We care about cities having more power over their energy future.

But I don’t know that I would have continued to do it if I hadn’t been inspired by David and his example of like, find those places in your community where you can make a difference. And I keep doing that work in part because I live here and I want my city to be better. I want my city to have more energy investment. I want people in my city to have more opportunity to lower their energy bills and to lower the pollution from things like waste incinerators or from gas-fired power plants we can replace if we make those clean energy investments.

I think there are so many examples of things that you can do. And, you know, it could be in housing, it could be in energy, it could be in composting, it could be around broadband access. It could be about helping to support local independent businesses. mean, ILSR touches on many of these, but there are other things that we don’t touch on that you could still do that might matter to you. Maybe it’s that you just want a better playground at your park and you figure out, well.

How do I, I can call up someone on my park board or I can call up Senator on city council and you can just start that conversation. It’s amazing what you can do just with ⁓ a little bit of effort and a little bit of organizing. And chances are you’re feeling something, somebody else is probably feeling it too. And I think David’s lesson is if you’re willing to persist and you’re willing to do a little bit of research, maybe you don’t need to read 70 pages over your lunch hour, but you know, understand the issue a little bit you can have a lot of power.

Danny Caine

John Farrell, thank you so much for coming on our show and sharing these great stories about David. I really appreciate it.

John Farrell

Danny, thank you so much for the chance to talk about David. He meant so much to me and so much to people at ILSR. I definitely miss him a lot. And it’s a pleasure to have a chance to talk about what my experience was alongside him.

Danny Caine

In preparing for my conversation with John, I spent a lot of time digging through David Morris’s writing from the 1970s, and I hope you do too. It really is something to see how far into the future David predicted With the dawning of solar cells. Another key pamphlet David wrote in the 1970s is Kilowatt Counter, and both are linked in the show notes. I’ve also linked to some of the groups and initiatives John mentioned, like Solar United Neighbors and Cooperative Energy Futures.

In the show notes, you’ll also find a link to ILSR’s Energy Democracy Initiative and a sign up for their newsletter.

Here at Building Local Power, we’d love to invite you, our listeners, into the conversation. If you have thoughts about this or other episodes, ideas for future guests, or if you just want to get in touch, send me a note at [email protected]. And as always, if you like what you hear, please like, subscribe, review, and share with your friends.

This episode of Building Local Power was produced by me, Danny Caine with the help of Reggie Rucker. I did the editing with help from Téa Noelle, who also composed the music. Thank you so much for listening and see you in two weeks.

A message to friends and allies reflecting on David's visionary ideas, rigorous thinking, and lasting impact on movements for a just, sustainable, and democratic world.

An appreciation for ILSR's co-founder, David Morris, on 50 years of accomplishments and impact.

In May of 1991, David Morris was featured in Minnesota Public Television’s (TPT) Portrait series on prominent Minnesotans. During the 25 minute interview David discussed...

In recognition of ILSR co-founder David Morris's life and work, we revisit David's BLP interview in 2017 about local power and the power of cities.