Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download | Embed Subscribe: RSS

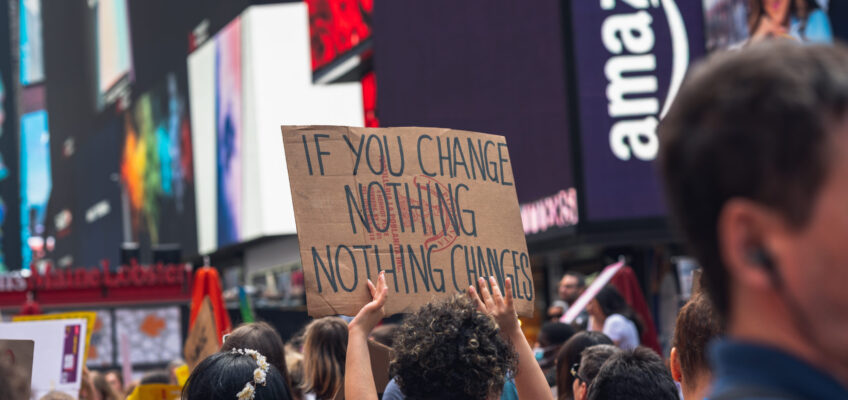

On this episode of Building Local Power, host Jess Del Fiacco and ILSR Co-Director Stacy Mitchell are joined by Zephyr Teachout, author of the new book Break ‘Em Up: Recovering Our Freedom from Big Ag, Big Tech, and Big Money. Zephyr shares her thoughts on building an antimonopoly movement, what she finds encouraging and discouraging in our current moment, and how she approaches antimonopoly work as a democracy activist.

On this episode of Building Local Power, host Jess Del Fiacco and ILSR Co-Director Stacy Mitchell are joined by Zephyr Teachout, author of the new book Break ‘Em Up: Recovering Our Freedom from Big Ag, Big Tech, and Big Money. Zephyr shares her thoughts on building an antimonopoly movement, what she finds encouraging and discouraging in our current moment, and how she approaches antimonopoly work as a democracy activist.

They also discuss:

- How monopoly power is harming communities, especially during the pandemic.

- How antimonopoly efforts have intersected with race throughout history, and why we can’t challenge corporate power without addressing racial injustice.

- The false division monopoly power creates between different people — from Uber drivers to chicken farmers — who all suffer under the same poor economic conditions.

- Why we must build alliances and put pressure on lawmakers at every level in order to challenge monopoly power.

“I think people understand that the more insidious form of these big corporations taking over democracy is they are governing themselves. They’re directly governing us, they are regulating, taxing, directing us, controlling how we live.”

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Hello, and welcome to Building Local Power, a podcast dedicated to thought-provoking conversations about how we can challenge corporate monopolies and expand the power of people to shape their own future. I’m Jess Del Fiacco, the host of Building Local Power and communications manager here at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. For 45 years, ILSR has worked to build thriving, equitable communities where power, wealth, and accountability remain in local hands. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | I’m here with Stacy Mitchell who’s the co-director of ILSR, as well as Zephyr Teachout who has a brand new book called BREAK ‘EM UP: Recovering Our Freedom From Big Ag, Big Tech, and Big Money, which is exactly what it sounds like, building an anti monopoly movement. Welcome to the show. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Thank you so much for having me on. This is… Talking with Stacy is basically my favorite way to spend time anyway. So to do it on this podcast is even more exciting. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | That’s so nice. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Stacy, do you want to get us started with questions? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Yeah, actually, I do. You have been on the front lines of the anti monopoly movement over the last few years. I mean, sort of early pioneer of trying to grow attention on this issue. And I’m curious about your assessment of where we are? And it’s sort of a question about why did you write this book now, but also just sort of bigger picture like where do we find ourselves in what’s happening, and are you encouraged, discouraged, some of both? |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Hugely discouraged and hugely encouraged. I laugh, but we’re in a really, really dangerous moment right now. And what is discouraging first, and then there’s a lot that’s really encouraging. What is discouraging is that the crisis of concentration of power, which has been growing for decades, has just been really exaggerated by this pandemic, and we are facing catastrophic collapse in small businesses, local power across the country. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | And if you’re listening, think about your own community, think about the devastation of restaurants, small pharmacies, small bookstores, small manufacturers across the country, and the impact that has on those business owners, the impact it has on those workers, the impact that has on those communities and then the impact on the power to fight power. You probably read the headlines and see in the news about disparate impact of COVID in communities of color. The business impact, it has been just horrific. Some people think that as many as a half of black small businesses might collapse due to this pandemic. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | And our response has been grotesquely insufficient. A band aid for a few months in the CARES Act. Not a serious response. So that’s the bad news. And that is quite bad. In terms of the movement, however, I see the modern anti monopoly movement, a movement for relocating power more locally and relocating power and people and not big corporations as really starting after the crash of 2008. When people across the country just saw this totally inadequate response to the devastating crash on the part of our mainline institutions. And in the last four or five years, groups like ILSR would, this is not an ad for ILSR, but I so deeply admire and love, have gotten much more attention for describing the world in a way that people are looking around for saying what’s going on? And groups like ILSR have got more attention. There are many more people who are organizing around this new groups like Athena, the powerful coalition to take on Amazon joining workers and small business owners to take on this Alexander the Great Angus con like business. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Incredible new energy in Congress, not just with David Cicilline’s great antitrust subcommittee, but I just had a wonderful event with Ro Khanna yesterday, who was very interested in concentration issues. I had an event with Congressman Chuy Garcia a few weeks ago, who’s very interested in these issues. There’s just growing interest in Congress and Congress often takes a long time to get there. On the one hand it’s moving, the Uber Lyft fight in California has been really powerful in bringing together people to fight against some of the platform monopolies. So there’s this incredible possible path of reclaiming our freedom and reclaiming a more equal, just thriving, even beautiful moral economy. And we’re in terrible shape. It’s not just that we have to act fast. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | The thing I most believe is that we do have to make anti monopoly part of all of our politics. The task right now that I’m proud to be a part of and you guys have been centralist is in shifting anti monopoly fights from between economists to making it central to public debate in all areas. When we’re talking about Ag policy, when we’re talking about finance policy, when we’re talking about pharma making anti monopoly part of everything we do, and looking at things through the lens of power in everything we do. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | I mean, the book is terrific. And one thing I loved about it is, it’s a really like fast read, it’s just engaging and you sort of you cover a lot of ground but it just feels very conversational in a way that’s terrific. There’s this central point that you make, that monopoly power, corporate power, we should understand as political power. And that seems very transformational, I think. Can you talk a little bit about what you mean by that and how it plays out? |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Yeah, I think this is really important. And just for my own background, I come from, I teach law at Fordham, and I have both taught and been an activist in money and politics and democracy or foreign voting rights reform for decades. And I came to anti monopoly work around the time of citizens united, because it became clear that as central as campaign finance reform is and I still think it’s absolutely central, we have a real democratic problem with concentrated power. And it’s a pretty frontal assault on self government. I come at anti monopoly as a democracy activist. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | There’s two main ways in which these big corporate entities, these big institutions are threatening government. One is by corrupting government through campaign finance funding, think tanks funding some of the fanciest universities in the country, recent evidence showing that a key economist who runs Yale’s Antitrust Institute does consulting for Amazon, as well as Google heavily funding George Mason. So there’s these tentacles everywhere. I think people understand that. The more insidious form of these big corporations taking over democracy is, they are governing themselves. They’re directly governing us, they are regulating, taxing, directing us, controlling how we live, and Stacy you’ve written wonderfully about this in terms of Amazon, and other big companies. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | But I think that sometimes there’s a tendency to be weirdly formal when it comes to what is government, to say it’s government if they’re called the mayor. And in every other part of life, we say, “Well, if it looks like a duck, talks like a duck, quacks like a duck, it’s a duck.” |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Right. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | I’m sure these big companies, when Amazon basically changes its rules about, it changes its algorithm, but let’s call it rules about prioritizing certain products that use certain different ingredients, that’s a regulatory move. It’s basically saying, this is the ingredient of choice. And we’re banning that kind of ingredient. When Tyson changes the rules about what kind of feed hormone is going to be used, that’s regulatory, because the impact on the different growers is as if a regulator had spoken. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | And the one I think that people really get right now is the way in which we have come to accept Mark Zuckerberg as our privacy regulator. So it’s like okay, our privacy czar has decided that our new privacy rules this month, are X or Y, and accepted it, that this is that we should be petitioning Zuckerberg to change his privacy rules that we all live under. And by the way, this is not a new form of government, this is a pretty toxic oligarchic model where people in government use their power at the top of a government to extract value from the people who they govern. It’s extractive, it’s toxic, it’s bad, we shouldn’t allow it. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | I have what is kind of a simple question, but one that I think about a lot, just the terminology. So people see these problems in their life. And there’s this growing awareness that something is wrong. I can see that these things are happening in my life and affecting me in the day to day. And I think it’s these big guys, influencing politics and influencing society, but are people actually, is the average American calling that monopoly power? Or is the connection not quite there? |

| Zephyr Teachout: | No, and yes. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | It’s because we say it all the time. And if people are listening to this podcast, they’re like, yeah, monopoly power. I kind of understand that structure and what that term means, but I don’t have a good idea if that is out there quite yet. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Well, there’s reasons to think it’s not, and there’s reason to think it is. The reasons to think that it’s out there much more than we think, is both anecdotally, I’ve run for office. When I first ran for office, it was for Governor of New York with my running mate, Tim Wu, who has been a real leader in this area, and we held anti monopoly. I would call them rallies, but at the time, nobody knew we existed there. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | But we held anti monopoly events at big cable companies, where people drop off their bill to talk about why these monopolies were awful. And people totally got it and they naturally slipped into like, oh, Teddy Roosevelt trust busting. There’s a language they could call on from high school, maybe from some sense of Roosevelt, like I know this is wrong. And when you said the word monopoly, they didn’t say, Oh, no, what are you talking about? There’s that and then there’s also recent polling, which shows that corporate monopolies are more hated than Wall Street, which takes a lot of hating. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | And then I just did some recent polling with data for progress showing that when asked pretty specific questions about, do you think we should break up big Ag, big tech, and big pharma? A majority of Americans left and right say, “Yeah,” a big chunk, like a quarter say, “I don’t know.” And then another 20% say “No.” Well, 20% saying no, it’s actually pretty small. I read in that polling and in my own experience, that people are hunting for language to describe this awful thing that is happening to them. And they are feeling governed and they are feeling debilitated by anger at not having control over their own lives whether you’re working for a big company or running a small business, but feel totally out of control or feel subject to arbitrary power. And that’s one of the things that I think is so toxic about this model is that people can get just shut off for no reason and in a disconnected, non responsive way. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | But I think when people then start digging into monopoly, and I really want to hear how you guys think about this, there is this like puzzle at the core of it is the word monopoly includes mono, one. And there’s a lot of self doubt, or people say, Well, I know it’s not just one distributor, I know, it’s not just one big tech company, it’s like two or three. And so they feel insecurity around it. And that is, then there’s been an aggressive 40 year campaign, trying to teach people to feel insecure. Tell them you don’t know what monopoly means, this is just a world for economists. Monopoly means something specific, it’s not what you feel. And I have struggled with the word monopoly for that reason. It has a very rich American tradition, which I love. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | I also like the word trust busting. The trust at least isn’t about just one. It’s this idea that there’s a network of power that is controlling you and we should stop it. What do you guys see in your conversations? Because I see both a real attraction and a lot of insecurity? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | I like the word monopoly a lot. And I think it’s a lot, we say anti monopoly a lot, because it’s bigger and better than antitrust. I think a lot of people are very much uncertain and feel unequipped to talk about what antitrust is. And of course, there’s a lot of ways in which policy structures the economy outside of antitrust. So we use anti monopoly a lot. I agree this mono problem and we sort of encounter that and try to say, “Hey, that’s not actually what it means. It means it’s an entity that has the power to call the shots.” |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Yeah. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | And then when you get into that, it’s like, “Oh, yeah, well, obviously Amazon has monopoly power.” They call all these shots, people easily see that. They dictate what the publishers do. They dictate what sellers do, they dictate all kinds of things, what workers do. And so that I think monopoly feels like the people’s term. And I do think we have to reclaim it in the sense of dislodging some of this stuff that has gotten attached to it kind of wrongly. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | And it actually, in some ways, I think goes to some of what you do in the book about this idea that somehow, like consumer choice is the solution to our problems. Because when you get in that, Oh, well, if there’s any option, any, like, I could stop using Facebook, or there is literally one other option in the market, even though maybe it’s tiny and incomplete, then it can’t be a monopoly because somehow people could just choose that other thing or choose to not use Facebook. And this doesn’t have anything to do with our experience as people operating in the world. And yet we’ve internalized this idea about making that choice as consumers. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | No, it’s totally right. And I mean, obviously, I write the book with an anti monopoly frame. I do think that there’s often a cluster of language that we can use altogether. And that trust, it’s not just antitrust, it’s that these trusts are terrible, but that we can… Recovering language is really important. And our tongues have been cut out by 40 years of people saying, “When you’re talking about too much power, you’re not talking about anti monopoly, you’re not talking about antitrust, go elsewhere.” I’ve had multiple conversations as you probably have, including during the Dodd Frank fight in the early 2000s, 2009, 2010, where I said we got to break up big banks and people would say, that’s not antitrust or that’s not anti monopoly. And I said, “Well, then how do we do it?” And they said, “Well, there isn’t a language for what you want to do.” |

| Zephyr Teachout: | One of my least favorite is people say well if this is a democracy problem deal with it and campaign finance reform, it’s like no, no, I know campaign finance reform we can’t deal with it just for campaign finance reform. But your point was a great, wonderfully illustrated during the big tech hearing. Where we saw Tim Cook saying, “Oh, no, no, no, we’re not a monopoly. Developers can go develop for PlayStation.” And you have these developer howls of ghoulish laughter, saying right, that’s how I’m going to build my business. And it’s this incredible, we overuse the term gas lighting, but it is a gas lighting of people’s human experience of power. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | I do think it’s helpful to point out that when Standard Oil was broken up it only had 65% of the market, just so people understand even when you’re going back to your Teddy Roosevelt fantasy, we’re never talking about one. It’s always about who has ability to dictate terms, it’s never been about one. Because otherwise, then you would do what Driscoll does, or the beers duopoly does, is you allow these cute little exceptions to exist. So you can say, “Oh, no, there’s duck, duck go. I’m not a monopoly.” |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Again thinking about in political terms, this is a classic political strategy. Is you allow for, maybe we overuse Russia as an example, but you allow for a opposition party to exist that will never be able to gain power. And it’s something that everybody in politics understands as a way to defend against illegitimate power is to claim that you have a rival when in power terms, you don’t. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Before we go to the next question, let’s take a short break. Thanks for tuning in to this episode of building local power. If you are enjoying this conversation, we hope you’ll consider making a donation to the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Not only does your support underwrite this podcast, but it helps us produce all the resources and research we make available on our website. Please take a minute and go to ilsr.org/donate to make a contribution. Any amount is welcome and sincerely appreciated. That’s ilsr.org/donate. Thank you so much. And now back to the show. We were talking to Zephyr Teachout about her new book, Break ‘Em Up. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | It does feel like we’re talking about power a lot more than we used to which it feels really good to me, at least among people who are engaged in social change work for a long time. We talked about behavior, let’s get companies to behave better. And the issue is we need good companies and not bad companies. And just always being sort of stuck in that framework for a lot of years. And it’s shocking, one of the facts you have in the book is that antitrust and monopoly issues were not in the democratic party platform from 1988 I think until 2016, something like that. I mean, 30 years basically, we just pretended like power and economic power wasn’t an issue even for the party that supposedly is concerned about the well being of ordinary people, to your point about losing a vocabulary, but it feels like we are starting to kind of turn the corner on that and dealing with the underlying thing? |

| Zephyr Teachout: | We are. And there’s a lot of great signs of it. The local work is really powerful, whether it’s the, I mentioned this before, but one of the reasons I care so much about the California Uber Lyft fight is because it is an example of a state legislature being pressured bottom up to take action against excessive private power. So it’s a proof that people feel so impotent in this area, but it’s a proof that this can happen at the state level. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | At the local level, I think people feel naturally both really empowered and disempowered at the same time. Empowered to do some of the great local work you’re talking about, and then just overwhelmed with how do we actually at the core take on, Monsanto being so big, how do we at the local level. And at the federal level, the power is at its peak, but the debate has been the most limited. So it’s starting to change. There was the great moments in the presidential campaign, when you saw three candidates, arguably four, we can debate Cory Booker, but Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, taking on big tech, and Amy Klobuchar really talking a lot about big Ag in the Iowa discussions, but elsewhere as well, and Klobuchar has actually also talked a lot about the impact on the news. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | So you suddenly saw three presidential candidates talking about taking on illegitimate private power, and being asked about it, and then it faded. I mean, then that moved away from the center of the debate. But I got to challenge anybody who’s listening, it still isn’t happening as much as I’d like on the congressional level. And I think that’s what’s going to be the 2022 is a real moment to make it part of everyday politics. So it’s not just what there’s a tendency to make it presidential or hyper local. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | And to build the movement, we need the connections between those two. So congressional level, real congressional level fights between people who have totally different visions of how to take on corporate power or who don’t think it’s a problem. And I’d say a majority of elected Democrats in Congress right now still don’t think it’s a problem. That’s my bet. So it’s going to have to come bottom up. A lot of the new Congress members really do. Pramila Jayapal, who’s a wonderful national leader on many issues. Ro Khanna, Keith Ellison in Minnesota. These are, I’m sure I’m leaving people out, but these are three leaders that I really watch because they have a national platform. They’re connecting anti-monopoly to other issues. And I think they’re really been a critical part of building this national discussion. Keith really is changing and I think one of the more exciting areas of change also is in increased recognition of the deep connections between race and concentrated power. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Well, so I was actually just going to ask if you could talk a little bit more about the connections between monopoly power and racial oppression, low wages, poor working conditions, because that’s what I feel like we haven’t quite gotten to in the political arena yet. But those connections are all there. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Yeah. So I come at race and monopoly power first from my perspective as a prior student of democracy and gerrymandering and redistricting. So one of the oldest tools for wiping out black power in the south was merging political districts. So if you had three political districts, in one political district a majority black electorate and two others about 60% white electorate, old tool of the Old South is merge them and then elect district wide representative, either at the state or congressional level, and that representative is going to be white, because the merger has wiped out the local black power. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | So then you apply that merger doctrine to, honestly I didn’t actually write about this in the book, but I was looking at similar things that happened with black colleges and universities how merger wiped out centers of black academic power. But when you look at mergers in the context of just businesses that merging it has a major bleaching effect. If you merge together as we have allowed happen in this country, so many of the funeral homes around the country, you end up with a big white owned, white financed SCI instead of unimportant locus of black political power, which has been the funeral home industry. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | And when you look at small businesses versus fortune 500, small businesses are far more likely to be run by a person of color. Fortune 500 I think it’s like 4% are run by a person of color. And then when you look at actually who’s controlling capital, it’s even it’s under 2%. It’s really incredibly bleached. So there’s a huge, huge, I think blind spot and that we think about merger policy as racially neutral in the same way that we thought about and talked about the CARES Act as racially neutral. When by putting a bazooka as David Dan like to call it, do trillions of dollars to the wealthiest institutions in the country and peanuts for small businesses. That’s not a racially neutral choice, that was a choice to support already powerful locus of white power, and really starve and destroy small business locus’s of economic power controlled by people of color. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | So I just think that we have to stop looking at merger policy and antitrust policy in racially neutral terms. And allowing these mergers has been a major driver of inequality, but also of racial inequality. And so when we want to turn that around, we want to turn the machine around and have it face the opposite direction instead, provide capital to local communities through community banks. That also is not a racially neutral choice, that’s a choice to support communities of color. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | But you asked something else that was sort of along these lines. I see that changing right now, I think people have a growing understanding of the interaction between race and anti monopoly. And I mean, we just like to be clear, a lot of the great anti monopolist of the early 20th century were terrible segregationists. So there’s a reason it’s like, you don’t want to hold on Woodrow Wilson. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Right. How do you wrestle with that? I mean, I’ve thought about it. And I guess I’ve sort of, is it that there is some kind of philosophical link between small scale anti monopoly politics and segregationism? Because there’s a lot of that. You know, Wilson is a good example, but there are others from that period, or is it just merely a coincidence? And are the forces of sort of pro monopoly if you will of that era justice race, is it that this there’s so much racism that… How do you think about that? |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Well, your second point is really important. It’s not like the pro monopolist should be held up as great heroes, either. I guess, I think about it in different ways. One is that it’s just always important to tell the truth. So you tell the truth about who Wilson was. You tell the truth about the impact of merger policy. And then I also think it’s important to point to other moments in history where there’s been two things, a deep connection between civil rights and abolitionism, both and anti monopoly to show that some other people have seen that connection. Like this really powerful movement into the mid late 19th century that very much saw white power and as illegitimate power and corporate power is illegitimate and the railroads were engines of both, we all know that railroads were engines of segregation and engines of oppressing others. That’s one moment. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Obviously Du Bois is a really important anti monopolist. And I talk about Du Bois and his own sort of understanding of the bargain between white northern power and entrepreneurial, racist politicians and business owners in the south, who basically make a bargain to come together to extract value and suppress black political and economic power. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | And I’m always on the lookout for these bargains. And we have modern versions of those bargains. I’m also interested and jumping around a little bit in Phil Hart, he was a really interesting character to me. Phil Hart was one of the authors of the civil rights legislation and is best known for his leadership and civil rights in this country. His two passions were civil rights and anti monopoly. And he actually went to his deathbed writing about what we should do next. And an anti monopoly laws because he understood that both segregation and concentrated corporate power were the two big challenges we had to a self governing society. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | And so that way of thinking I think is important. I want to have a whole conference on this question about the relationship between race and corporate power in history. Is to me the big question mark is Reagan, and the Reagan wrecking crews approach? So Reagan’s Wrecking Crew, Baxter Meese, this California group of white authoritarians come in. And if you look at their own language, they put anti trust at the top of their agenda. They say, like, changing the way that we approach antitrust. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | For us today that’s kind of weird. Like, it’s interesting and weird. Now they succeeded and it’s been awful for being part of that. It’s like okay, so why was Reagan’s Wrecking Crew not just deregulatory, but why did they care so much about antitrust? And why was it so tied to their effort to undo the successes of the civil rights movement? Which it clearly was. So you have on the one side people who are fighting for civil rights and for stronger anti monopoly laws and the other side, Meese, Baxter, California that’s coming with Reagan, who have a kind of… These are question marks to me, it seems like they have an authoritarian streak. Like we want centralized power that’s one way to understand it, is they just wanted centralized power and these are two ways to get it. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Another way to understand it is it was a bargain. So it’s like okay, we’re going to go, Reagan was not that subtle about his vision of returning to a white America. The winks and nods are right there. That’s the dog whistle as you might call it, right there. So is he going to sell that return to corporate America or is the corporate American thought Oh, the way that we get back in is by fanning racial anxiety? Those are questions for me. But from the 40s onward, those two have come in together sort of this corporate authoritarianism and white nostalgia come together. I mean, how do you see that connection? |

| Stacy Mitchell: | No, I think that, that’s right. I mean, I think, part of the reason that there is in the early 20th century, a certain anti monopoly activity in the south is that it’s also in the West, that it really has to do something with being outside the center of financial power. And I think you’re absolutely right about this observation of Wall Street and moneyed interests and the north and like the deal that they cut with white supremacists in the south about keeping this house economy structured in a way that excluded African Americans. And it also excluded a certain kind of economic development because that meant more opportunity for people to sort of insist on this ongoing kind of agrarian sharecropping model essentially. And that there’s the northern financial power has complete hand in bringing that about. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | And then yeah, you see these really interesting movements. I mean, there’s that populist movement in the 19th century that brought together white and black farmers to call for a reorganization of power is like one of the most, instructive and interesting periods of our history and this relationship between, in the civil rights movement again, is kind of another moment where black owned businesses in the south were instrumental in being able to kind of be pillars of allowing for the making part of that movement happen and being able to support it in a way because they were businesses and had some level of independence. And I think we sort of remember the civil rights movement kind of collectively around things like voting rights and segregation and public spaces. But there was a huge part of it that was economic. And I think part of the 40 years that we’ve had recently this kind of blot we’ve like swept that away as though that didn’t exist. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | I think you’re right about telling the truth and recovering the history is such an essential part of like figuring out how we got here and how much racial oppression economically and monopoly power are like intertwined and that if we want to unravel one, we’ve got to unravel the other. And we can’t succeed if we’re only pulling on one of those threads. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Yeah, and I start the book with stories that I just, I think that we have to then find new stories that show how people who are subject to this regime are connected. Who are living in like what seemed to be very different worlds. So I start the book telling stories of chicken farmers and trying to connect that to what’s happening to Uber drivers and connect that to what’s happening to restaurant owners, what’s happening to people who run a laundromats. All of whom are being told that they are totally different and should hate each other, but are in really living under very similar, really humiliating economic circumstances. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | So finding this is returning to the possibility of the black and white farmers working together and finding new alliances, both alliances between urban and rural people who are both subject to monopolize regimes, finding alliances between small business owners and franchisees, who are of course small business owners, and people who work for Amazon. That is quite… And I know this is the work that you guys are doing. It is the most difficult work and also, I think it’s essential. Like I think that finding those alliances, there’s no academic way around it, that actually creating political power with those alliances is the necessary step to taking on this kind of concentrated power. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | That’s totally right. So, my question is, you talked about, the next sort of arena in campaigns and in politics being around congressional fights, and how do we make monopoly part of congressional races. Are there sort of three issues or three, you know, like, what are the things that could help drive that? |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Okay, I said that, I got to tell you the last three weeks I’ve been on a state kick. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Okay. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | I just got to, I shouldn’t say that I was… And the state kick is, I’ve been so excited by and so this is where call your Governor, and your state lawmakers. I’ve been so excited by the effort to cap delivery fees during the pandemic. Like delivery fees are killing restaurants that are already being killed by the pandemic and people kind of get it. They get that Grub Hub should not be taking a huge percentage and we should be supporting restaurants. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | So my excitement is once states realize they can do that, cap delivery fees, well guess what? You can actually have caps on what Amazon can do in your state. You can actually shape what Monsanto or Mayor can do in your state. And then obviously, that’s a little complicated. There’s some federalism issues that we have to get over, but I feel like this delivery fee fight is revealing a state power that people just… Every time I talk to people about states they feel like it just sounds impossible. Just sounds impossible. But I mean, I’d be interested to see what you think. I think this doesn’t sound impossible to people. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | No, it sounds eminently doable. And you know, a bunch of cities have already done it and at least one state has done it, New Jersey. And we’ve joined with the economic liberties project and a whole bunch of restaurant groups and others to do this protect our restaurants. I think it’s protectourrestaurants.org, so it’s both like a petition to the FTC, but also like a how to guide to get your city or your state legislature to do this. And I think you’re right, it is like a kind of gateway, a gateway drug to like, “Hey wait, we were charged, we could actually set some rules around these monopolies and we could do it right in our city or at our state level.” |

| Zephyr Teachout: | [crosstalk 00:37:48] tying contracts or predatory pricing. I just feel like yeah, that’s a big issue, but it feels too big. Delivery fees isn’t too big. And so then If you just get to the broader demand of like, why are you allowing these monsters to control us? It’s the lawmakers job to figure out how. Just keep making that demand and if the monster’s still controlling us make it louder. I love the restaurants campaign. That’s why I’ve been on this like, I just love what you guys are doing there. So thank you. Well in case, [inaudible 00:38:25] as we started as my fan mail for ILSR [inaudible 00:38:30]. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | We’ll take it, thank you. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | I do want people to read this book because I care so much about these issues. And it’s both to you who are listening, but also to your aunt or niece, who maybe ideally, has not been listening. Here is a book that hopefully will depress them for 30 minutes and then excite them for a few hours. |

| Stacy Mitchell: | Yeah, and I will give one last plug for the book, which is really terrific. Not only is it very readable and conversational and like interesting. I was just like, I was engaged throughout and sort of knits together these things that you kind of in your mind know go together, but hadn’t really thought about it that way. But I think the whole last third is dedicated to what do we do about it and like all of the possibility about how you both build the movement and the politics and the language and the tools. And that’s what I think is really nice. I think this isn’t just a book about a problem, It’s a book about actually, where do we go with it? |

| Zephyr Teachout: | Well, thank you so much for having me on the podcast. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Thank you for talking with us. |

| Zephyr Teachout: | As they used to say150 years ago, down with monopolies. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | Thanks again for tuning into this episode of the Building Local Power podcast from the Institute for local self reliance. You can find links to Zephyrs book and everything else we discussed today by visiting ilsr.org and clicking on the Show page for this episode. That’s ilsr.org. While you’re there, you can sign up for one of our many newsletters and connect with us on social media. |

| Jess Del Fiacco: | You can also help us out with the gift that helps support our work, including the production of this very podcast. You can also help us out by rating this podcast and sharing it with your friends wherever you find your podcasts. The show is produced by me, Jess Del Fiacco and Zack Freed. Our theme music is Funk Interlude by Dysfunction AL. For the Institute For Local Self-Reliance, I’m Jess Del Fiacco and I hope you’ll join us again in two weeks for the next episode of Building Local Power. |

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes, make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes, make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

If you have show ideas or comments, please email us at info@ilsr.org. Also, join the conversation by talking about #BuildingLocalPower on Twitter and Facebook!

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | RSS

Audio Credit: Funk Interlude by Dysfunction_AL Ft: Fourstones – Scomber (Bonus Track). Copyright 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license.

Top Photo: iStock.com

Inset Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and, for monthly updates on our work, sign-up for our ILSR general newsletter.