A selection of recent news stories with an ILSR insight into “The Public Good.”

Stories in this Newsfeed:

Trade Agreements: What Are We For? | Democracy at Risk: Gerrymandering | Democracy at Risk: Voter ID | Leopold Kohr and the Curse of Bigness | The Privatization of Medicaid | Why Aren’t More Financial Firms Taken to Court? | How Congress Tried to Help the Sick and Ended Up Breaking the Bank

Trade Agreements: What Are We For?

Trade Agreements: What Are We For?

Opponents of trade agreements past, present and proposed focus almost entirely on their flaws and dangers. Given the imminent possibility of a vote on the TransPacific Partnership (TPP), this is surely understandable, but it lends credence to the facile argument of supporters that we resist trade per se. Which is nonsense. We all recognize the need for international rules governing commerce just as we recognize the need for national and state rules. The question is, what should those rules be?

In the United States this question has had to be addressed internally as well as externally. The U.S. federalist system lends itself to a race to the bottom as states compete with each other for mobile capital and businesses. We’ve made rules that inhibit such socially harmful competition (and made many more rules that aid and abet it). The first federal minimum wage, for example, was introduced in part to inhibit manufacturers from moving to the low wage south from the higher wage north.

What would be the elements of an equitable, progressive, democratic trade agreement? In 2015, as the debate about TPP and its sister agreement, TransAtlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) James Love, Director of Knowledge Ecology International offered some thoughts. As he noted, we were (are) engaged in trade deals involving 29 of the 34 OECD countries, affording us an historical opportunity to make international rules that discourage corporations from avoiding taxes by shifting profits to countries where their presence may consist of nothing more than a mailbox. He offers the Multi-state Tax Compact (MTC), in effect in the United States since 1967, as a possible model. The MTC allocates corporate profits among states according to a three-factor formula that includes plant, employees and sales. When states require detailed reporting by corporations this can work well.

Love touches on other proposals: requiring data from government supported clinical trials on drugs and vaccines be publicly available; requiring annual paid vacations and time off from work with pay for maternity leave as country average incomes increase; mandatory minimum seat space for passengers on airlines.

Explaining why we are against bad trade agreements is a priority. But we also need to explain what kind of trade agreements we are for by fleshing out the elements of a trade agreement that maximizes the public good.

Democracy at Risk: Part I

Democracy at Risk: Part I

In the 2010 elections Republicans focused with laser like accuracy on capturing state legislative seats. Their handsomely financed and well-coordinated effort proved wildly successful. Going into the election, Democrats held a 60-36 advantage in state legislative chambers. After the election, the advantage dramatically shifted to the Republicans 57-39. In 25 states Republicans controlled both houses of the legislatures.

As David Daley, editor in chief of Salon, explains how they went about it in his new book, Ratf**cked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy., the winners immediately set themselves to ensuring permanent control.

The project was called, fittingly, REDMAP, for Redistricting Majority Project. The effort involved the Republican Governors Association, U.S. Chamber of Commerce and ALEC, with funding by Walmart, tobacco companies and individual millionaires and billionaires. Their tool was an unprecedentedly finely-detailed computer model that could go block-by-block to effect a gerrymander that political scientist Sam Wang described as “historic and different from others in the modern era.”

The effects have been dramatic. Until 2010 Ohio Congressional districts were roughly evenly divided between the two parties. In 2012, while Ohioans cast 52 percent of their votes for Republican Congressman. Their House delegation is 75 percent Republican.

In Pennsylvania, Democratic candidates for the House received half the votes, but Republicans won three-quarters of the Congressional seats. More than half the voters in North Carolina voted for Democrats, yet Republicans filled about 70 percent of the seats. Democrats drew more votes in Michigan than Republicans, but took only 5 out of the state’s 14 congressional seats.

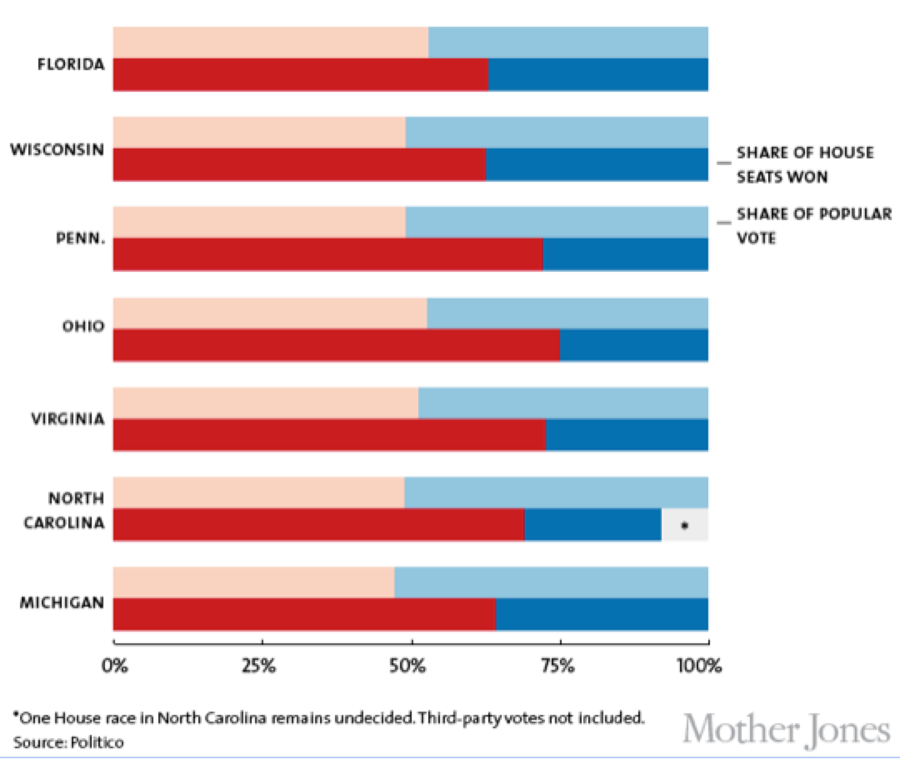

Right after the 2012 election Mother Jones published a visually impressive chart comparing the percentage of House seats won by each party to the percentage of the popular vote that party won. A fair election would be one where the dark blue line was roughly the same length as the light blue line.

Gerrymandering’s Impact on the 2012 Election

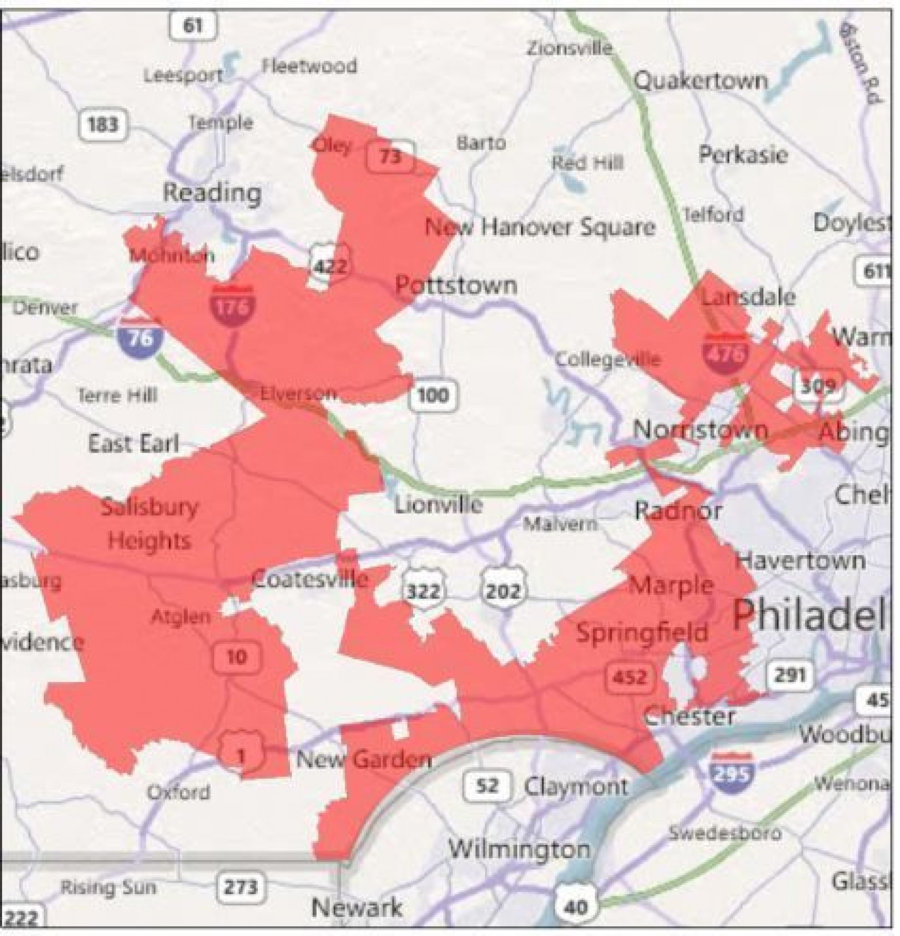

Sometimes the shape of gerrymandered districts verged on the bizarre. Here’s the map of the 7th Congressional district in Pennsylvania.

One federal judge lamented the outcome of this unprecedented redistricting process: “the fundamental principle of the voters choosing their representative has nearly vanished. Instead, representatives choose their voters.”

Federal courts have been reticent to intervene and even when they do, the impact is muted. North Carolina’s gerrymandered maps were drawn in 2011 but it wasn’t until February 2016 that a federal court overturned them. In the interval the state had two congressional elections and sent four years worth of congressional delegations to Washington. As ThinkProgress observes, “the message to lawmakers is clear: go ahead and draw the most self-serving maps you can manage, because even if they are struck down it will take the courts years to do so.

It gets worse. Within a few days of the court’s decision the North Carolina legislature convened a special session and promptly redrew the map in a way only marginally better than the previous one. Again a lawsuit was filed. In June 2016 the same federal court that had found the North Carolina redistricting racially biased in February refused to intercede. It did not that one of the key legislators who drew the new map had declared, “[W]e want to make clear that we are going to use political data in drawing this map. It is to gain partisan advantage on the map. I want that criteria to be clearly stated and understood. I’m making clear that our intent is to use the political data we have to our partisan advantage.” Which led the judges to comment, “The Court is very troubled by these representations.” Very troubled but powerless, they insisted. “Nevertheless, it is unclear whether a partisan-gerrymander claim is judiciable given existing precedent.” Based on precedent, “the Court’s hands appear to be tied.”

Given the aftermath of the 2010 election, expect elections for state legislatures in 2018 and 2020 to be bitterly contested. Spending in 2018 may reach levels reached only in Presidential election years.

For those wanting to bring fairness to the redistricting process, there is a non-judicial remedy. Take control out of the hands of self-serving legislators and parties and invest it in nonpartisan citizen commissions. In the 14 states that have direct initiatives this can be accomplished by a majority statewide vote as has already occurred in California and Arizona. In 2015, by a 5-4 decision the Supreme Court upheld Arizonans right to do this, a decision that also upheld California’s independent commission. Five other states have semi-independent commissions: Washington, Idaho, Montana, Hawaii and New Jersey.

Whatever happens, at least the next two elections should be guided by the political maxim: Vote for your local state legislator as if the Congress depended on it.

Democracy at Risk: Part II

Democracy at Risk: Part II

In 2008, the Supreme Court upheld an Indiana law that required all voters casting a ballot in person to present a U.S. or Indiana photo ID. The facts of the case were not in dispute. Those least likely to have state-issued identification were disproportionally poor and nonwhite. The only voter fraud addressed by photo IDs is voter impersonation fraud, which was practically nonexistent.

None of this mattered to the Justices. John Paul Stevens, writing for the majority, insisted the burden of proof should rest not on the state to justify new voting restrictions but on the citizenry to prove they created a burden. And not just an incidental burden. He elaborated, “Even assuming that the burden may not be justified as to a few voters, that conclusion is by no means sufficient to establish petitioners’ right to the relief they seek.”

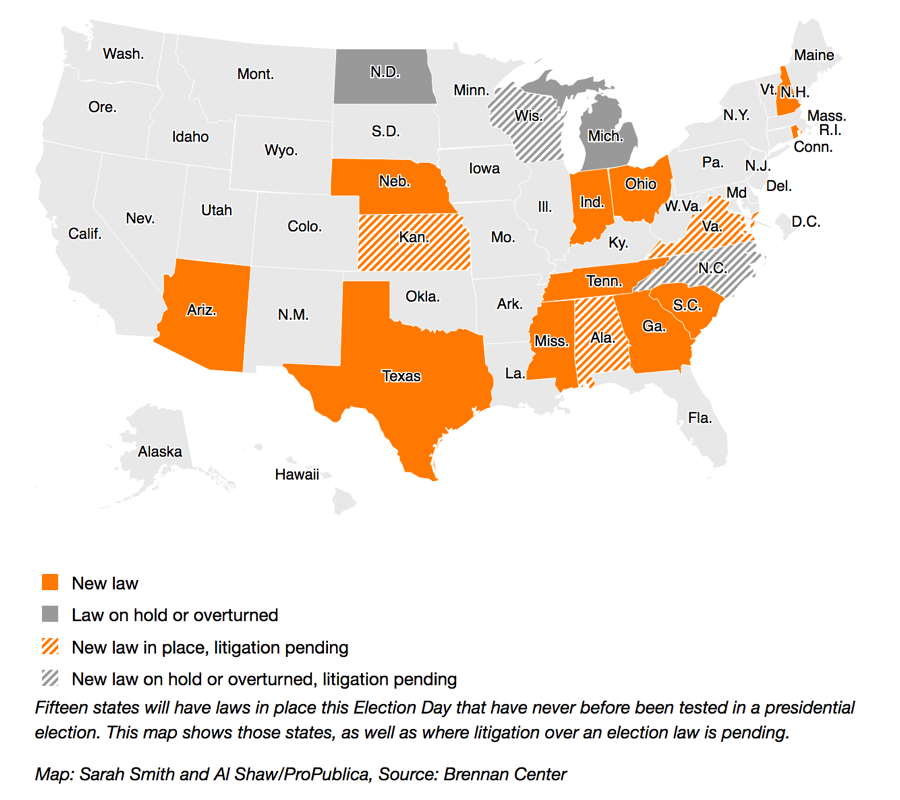

The decision reversed a century-old dynamic during which the franchise had been broadened and the ability to vote facilitated. Since 2010, 23 states have either introduced more restrictive voter procedures or tightened those in operation.

In 2013, the Supreme Court, by a 5-4 decision, enabled disenfranchisement by striking down the heart of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the provision that required pre-approval by the federal government of changes in election laws. This freed the nine covered states and dozens of counties in New York, California and South Dakota to change election laws without advance federal approval. They can still be sued, but only after the fact.

Fifteen states enacted new voting laws for Presidential elections. Since 2013 such suits regarding these laws have been wending their way through the courts.

Early this summer Courts have halted the implementation of voter suppression laws in North Dakota and North Carolina.

North Carolina’s voting restrictions, introduced the day after the 2013 Supreme Court decision added a strict photo-ID requirement, cut a week off of early voting, and ended same-day registration, preregistration and out-of-precinct voting. A Circuit Court found the law’s provisions “target African Americans with almost surgical precision,” and explained, “We can only conclude that the North Carolina General Assembly enacted the challenged provisions of the law with discriminatory intent.”

The status of all these lawsuits, as of mid August, can be found at ProPublica.

Leopold Kohr and the Curse of Bigness

Leopold Kohr and the Curse of Bigness

Writing in the Guardian in 2011, English writer Paul Kingsnorth described the contemporary political and economic dynamic:

“One man who would not have been surprised by this crisis of bigness, had he lived to see it, was Leopold Kohr,” Kingsnorth pronounced.

Kohr, described by Colin Ward as Austrian by birth, British by nationality, Welsh by choice to this day remains largely unknown. It was a student of Kohr’s, Ernst Schumacher, who would bring the issue of scale to a broad audience in 1973 with the publication of Small is Beautiful. Schumacher asked Kohr, who he viewed as the originator of many of the principle ideas of the book, to be his co-author. With characteristic humility and graciousness, Kohr declined.

In 1994, the year of Kohr’s death, Ivan Illich offered a personal portrait of his friend, colleague and long time mentor in a lecture to the Schumacher Center for New Economics, “Kohr was an eminently unassuming man. I would even go so far as to say that he was radically humble, and this aspect of his thought and character tends to disqualify him from inclusion in textbooks. It may also have contributed to the fact that so few have grasped the core of his argument: the prominence he gives to proportionality.”

Kohr begins his seminal book, The Breakdown of Nations, written in 1951, published in 1957, with his central thesis, “Wherever something is wrong, something is too big.”

“As the physicists of our time have tried to elaborate an integrated single theory, capable of explaining not only some but all phenomena of the physical universe, so I have tried on a different plane to develop a single theory through which not only some but all phenomena of the social universe can be reduced to a common denominator. The result is a new and unified political philosophy centering in the theory of size. It suggests that there seems only one cause behind all forms of social misery: bigness.”

For Kohr, the nation state lacks legitimacy. They are,

“artificial structures, holding together a medley of more or less unwilling little tribes. There is no `Great British’ nation in Great Britain. What we find are the English, Scots, Irish, Cornish, Welsh, and the islanders of Man. In Italy, we find the Lombards, Tyroleans, Venetians, Sicilians, or Romans. In Germany we find Bavarians, Saxons, Hessians, Rhinelanders, or Brandenburgers. And in France, we find Normans, Catalans, Alsatians, Basques, or Burgundians. These little nations came into existence by themselves, while the great powers had to be created by force and a series of bloodily unifying wars. Not a single component part joined them voluntarily.”

Even in the early 1950s Kohr, a European, worried about a European project that was trying to weld together states large and small into a single decision making unit. He worried about the creation of a stifling and remote bureaucracy and the local tensions that could create. “Europe’s problem – as that of any federation – is one of division, not of union,” he declared. The challenge was to decentralize decision making, both economic and political, while closely cooperating on an international scale.

Kohr drew a map to visualize a Europe of mostly equal sized states based on culture and history that would federate and confederate to act internationally.

Given contemporary developments in the Mideast, it is regrettable that we don’t have a map by Kohr envisioning the division of “artificial structures, holding together a medley of more or less unwilling little tribes.” We do know that part the region was encompassed within a governance structure Kohr much admired. He writes:

“…the most significant illustration of the small-state principle as the mainspring of federal success… one of the most unique political structures of the past, thought it invariably produces nothing but jolly laughter amongst our sophisticated modern theorists when its name is mentioned… is the Holy Roman Empire, …a loose federation uniting in a single framework most German and Italian states, and lasting for the fantastic period of a thousand years. . . . The reason for its singular success and its extraordinary duration was that it was easy to rule. And it was easy to rule because of its small component parts. Like every political organism, it was besieged by thousands of frictions and problems. But none of these ever outgrew the small power of its central government…

When the Empire eventually began to break down, it was not because it was ramshackle and weak. That was the reason for its success. It was because at last, after nearly a thousand years of romantic and ineffectual existence, strength began to develop in its corners, producing on its soil the unified great powers of Prussia and Austria. Regional union thus meant not the preservation but the destruction of this much-ridiculed though great and truly international realm. What had survived a millennium of small-state existence was finally smashed by the cancer of its own great powers.”

Sixty years after its publication, the Breakdown of Nations still has much to teach us.

The Privatization of Medicaid: Refusing to Learn from Experience

The Privatization of Medicaid: Refusing to Learn from Experience

In the early 2000s, several states began moving away from a publicly operated fee for service system to one managed by private, for-profit corporations paid a flat fee per patient. The results were not pretty.

Analyses of data from the 2005 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Study found that while the money paid to private companies for Medicaid and SCHIP were about the same as for publicly operated systems, total medical spending was 26–30 percent higher. The reason was that the private insurer shifted much of the cost to the patient. The consumer’s out-of-pocket spending was 600–750 percent higher under private insurance than under public insurance.

In 2009 Massachusetts transferred 30,100 green-card-holding immigrants from its state-subsidized insurance program to a for profit corporation. To save money, the state paid a low $1,500 per enrollee. Eight months after the plan became active, a brief study in the Aug. 5 New England Journal of Medicine accused the contractor of “rationing by inconvenience.”

In New Jersey, private Medicaid plans enrolled large numbers of low-income families and then denied up to 30 percent of their claims for hospital care. Early attempts by Montana and Massachusetts to provide private Medicaid funding in mental health had dismal results.

In 2013, Kansas, either oblivious to past failures, undeterred by them or simply not caring, Kansas voted to contract with three for profit companies to run Medicaid as a managed care system.

In December 2015, officials at the Lawrence Memorial Hospital (LMH) testified to a legislative panel about their experience. To hold down costs the three insurance companies routinely denied legitimate claims. Only about a third of the denials that LMH appealed were eventually paid. By comparison, LMH had about a 90 percent success rate with appeals to Medicare.

The problem had worsened steadily throughout the years KanCare had been in place. LMH has had to double the number of employees in her department who deal with claims and appeals just to keep up with the volume of work.

In April 2016, undaunted by the experience of its neighbor 350 miles to the southwest, Iowa decided to privatize Medicaid, adopting the Kansas model of using three contractors to operate the state’s $5 billion Medicaid program serving 550,000 people. Two were the same as those in Kansas.

By July sobering findings from a survey of more than 400 Iowa doctors, hospitals, local clinics and non-profit health care providers were released.

- 90 percent say privatization has increased their administrative expenses

- 79 percent are not getting paid on time

- 66 percent say when they do get reimbursed, it’s at lower rates than agreed upon

- 61 percent say privatization has reduced the quality of services they can provide

- 46 percent of providers are planning to reduce services

Undaunted by the experiences of Iowa and Kansas, North Carolina has become the latest to privatize its $15 billion Medicaid program serving one million people. Once again three insurers will be awarded contracts to offer statewide Medicaid managed care plans. Over time the state will eliminate the state Medicaid office.

In 2013, when he first proposed privatization, North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory offered several specific reasons explaining why a drastic overhaul was required. Each was quickly rebutted by those knowledgeable about the existing Community Care of North Carolina (CNCC) program.

McCrory insisted the CNCC “does not focus on measuring and improving overall health outcomes for recipients.” The Center for Medicare Advocacy (CMA) pointed out that the CNCC ranked in the top 10 percent of the nation in HEDIS scores (a widely accepted health care quality measures) for diabetes, asthma and heart disease when compared to commercial managed care and that it boasted a widely admired process for measuring the quality of care and improving outcomes.

The Governor asserted the CNCC “lacks a culture of customer service and operates in silos, making it difficult for recipients to know where to go to receive the right care.” The North Carolina Justice Center (NCJC) noted the Medicaid card sent to people when they sign up includes the name, address and phone number of the Medicaid recipient’s family doctor or health practice.

McCrory contended the state’s current Medicaid system “makes it difficult for doctors and other healthcare providers to participate because of a complex system with uncertainty, high costs and burdensome paperwork”. The NCJC pointed to a recent study in the respected national journal Health Affairs, that found 76.4 percent of physicians in NC actively accepting new Medicaid patients compared to a national average of 69.4 percent. In Florida, where a shift to privately managed care companies had been operating for years, the rate of physician acceptance of Medicaid is only 59.1 percent.

McCrory maintained the CNCC “experiences unpredictable cost overruns…” The CMA noted that the CNCC’s innovative fee-for-service delivery and payment system consistently ranked as one of the most cost-effective Medicaid programs in the country. An outside evaluation by Milliman, CCNC saved North Carolina $1.5 billion from 2007 to 2010 and had the lowest Medicaid spending growth in the nation.

The examples of Kansas, Iowa and North Carolina, as well as many other states, supports the contention that the privatization of public health is not evidence-based but faith-based, an effort guided by ideology, not reason.

Why Aren’t More Financial Firms Taken to Court?

Why Aren’t More Financial Firms Taken to Court?

We know Wall Street firms and individuals repeatedly broke the law, a crime spree that result in millions losing their homes and their jobs. We’re furious that so few have been brought to justice.

The recent case of Countrywide Home Loans offers some insights as to why, more often than not, Wall Street has not had to pay for their crimes.

In 2007, the largest mortgage provider in the country rolled out a new lending program the bank called the “hustle.”(really!)

Let’s let Jesse Eisinger of ProPublica take the story from there.

“Countryside, like most mortgage lenders, sold its loans to Wall Street banks or Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two mortgage giants, which bundled them and, in turn, sold them to investors. Unlike the Wall Street banks, Fannie and Freddie insured the loans, so they demanded only the ones of the highest quality. But by that time, borrowers with high credit scores were getting scarcer, and Countrywide faced the prospect of collapsing revenue and profits. Hence, the hustle program, which “streamlined” Countrywide’s loan origination, cutting out underwriters and putting loan processors, whom the company had previously deemed not qualified to answer borrowers’ questions, in charge of reviewing loan applications. In practice, Countrywide dropped most of the conditions meant to insure that loans would be repaid.

The company didn’t tell Fannie or Freddie any of this, however. Lower-level Countrywide executives repeatedly warned top executives that the mortgages did not fulfill the requirements. Employees changed data about the mortgages to make them look better, sometimes increasing the borrower’s income on the forms until the loan looked acceptable. Then, Countrywide sold them to the mortgage giants anyway.

At one point, the head of underwriting at Countrywide wrote an alarmed email, with a list of questions from employees, such as, does “the request to move loans mean we no longer care about quality?”

Federal prosecutors sued Countrywide for fraud and in 2013, Bank of America, which had by then taken over Countrywide, was found guilty by a jury and later ordered by a trial judge to pay a $1.27 billion judgment to the government.

Trial Judge Jed. S. Rakoff’s remarkably compelling, detailed and accessible decision should be widely read. The hustle program, he concluded, “was from start to finish the vehicle for a brazen fraud…driven by a hunger for profits and oblivious to the harms thereby visited, not just on the immediate victims but also on the financial system as a whole.” He observed, Fannie and Freddie “would never have purchased any loans from the Bank Defendants if they known that Countrywide had intentionally lied to them.”

In May 2016 an Appellate court overturned the conviction and monetary penalty. The decision was unanimous.

The Court’s reasoning will make no sense to the reader nor the general public. Nor should it.

“In the relevant contractual provisions, Countrywide “makes” or “warrants and represents” certain statements (i.e., present-tense acts), including that the future transferred loan will be investment quality… The use of a present-tense verb in a contract indicates that the parties intend the act… to occur at the time of contract execution, not in the future.

The Government urges us to read the relevant contract provisions as, in essence, promises at execution to make future representations as to quality. The language of the provisions, however, constitutes a present promise, made at the time of execution, to provide investment-quality loans at the future delivery date. … Thus, to the extent its fraud claim is based on these contractual representations of quality, it necessarily fails for lack of proof that, at the time of contract execution, Defendants had no intent ever to honor these representations.”

The judges never questioned that the mortgages sold to Fannie and Freddie were of low quality. But as Michael Hiltzik of the Los Angeles Times writes, they concluded there was no evidence “the executives who signed those contracts intended at the time to stuff the pipeline with toxic junk. It just turned out that way.”

Because there was no intent to defraud when the contracts were signed this was merely a case of breach of contract, not fraud, the penalties for which are much lower than those for fraud. The guilty party may only have to give back the money it made from breaking the contract.

Dennis Kelleherm a former corporate lawyer, now CEO of the financial watchdog group Better Markets explained to Hiltzik the impact of such a decision, “You wonder why the American people are so cynical?… It’s because there’s an endless reservoir of ways to figure out how to hold no one accountable for illegal conduct.”

How Congress Tried to Help the Sick and Ended Up Breaking the Bank: What to Do About the Price of Drugs?

How Congress Tried to Help the Sick and Ended Up Breaking the Bank: What to Do About the Price of Drugs?

In 1983 Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act. Orphan drugs treat conditions that affect less than 200,000 people. To encourage drug companies to research these drugs, the government offered handsome incentives: paying half the cost of the clinical testing plus the fees to bring it through the FDA approval process plus seven years of marketing exclusivity.

Perhaps realizing that this opened the door to gaming the system and price gouging, The Washington Post reports that Congress quickly passed a bill that would have revoked exclusivity if the drug’s target population grew to more than 200,000. President George H.W. Bush pocket vetoed it. A proposed bill that would have terminated the exclusivity early if a drug reached $200 million in annual sales never passed.

Since the Act passed, the median launch price of orphan drugs for chronic use has doubled every five years. The average annual cost for newly approved orphan drugs is an astonishing $112,000.

More than 400 treatments have been approved since the law passed. The proportion of new FDA-approved drugs submitted as orphan drugs has risen to 41 percent.

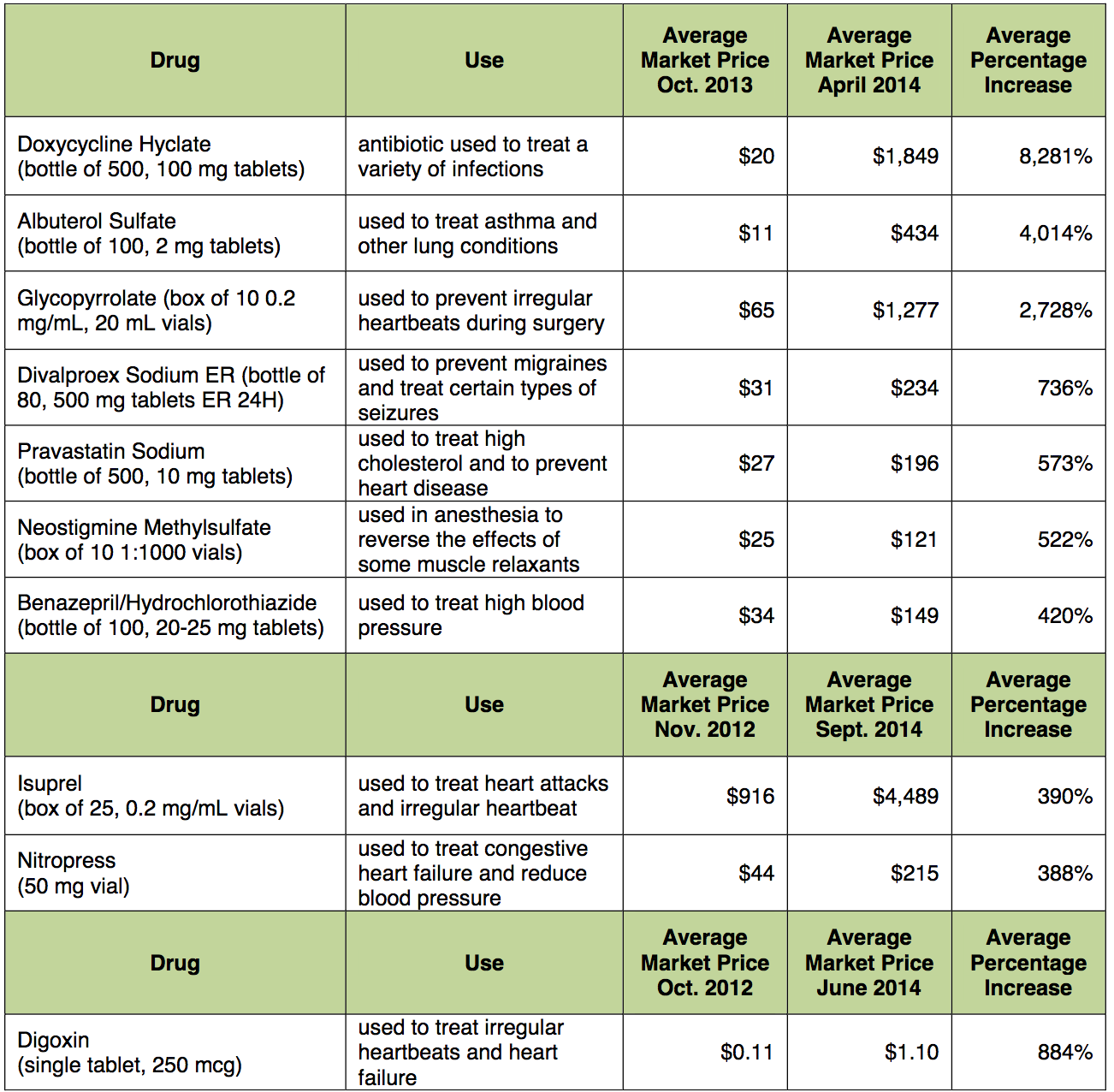

Drug companies have gamed the system by gaining orphan status for their drugs hat have long been on the market and then dramatically raising their prices.

- An old glaucoma drug was reborn as an orphan for a disease called periodic paralysis. Its price soared from $50 a bottle to $13,650.

- A decades-old pregnancy drug received orphan approval in 2011 as a treatment to lower the risk of preterm birth. The price skyrocketed from $20 to more than $1,400 a dose.

A growing number of doctors believe the Act may have backfired by making existing drugs harder to get. In February 2016, dozens of physicians signed a letter published in the journal Muscle and Nerve, warning “What is particularly troublesome to us is a ‘loophole’ in the Orphan Drug Act that allows companies to receive FDA market exclusivity . . . for older, existing drugs.”

Economist Dean Baker offers a non-regulatory solution to the problem of price gouging of orphan drugs. Make the orphan drugs 100 percent public. Have the government pay for the other half of the cost of the clinical tests. He predicts the drugs would become “available at generic prices, which would likely be less than one percent of the cost of the average new orphan drugs.”

The problem of inflated drug prices, of course, goes far beyond orphan drugs. In the news most recently is the case of Mylan, a pharmaceutical company that acquired the rights to the EpiPen, a patented injection device for a drug that sells for a couple of dollars a dose. It acquired those rights in 2007. At the time the list price for two EpiPens was about $100. Its most recent price hike brings the cost to over $600 even the comparable price in France is $85. In the last few years, the price of generic drugs in general has soared. Turing Pharmaceuticals increased the cost Daraprim, a drug used by some cancer and AIDS patients, from $13.50 to $750 last year.

A recent report jointly issued by Representative Elijah E. Cummings and Senator Bernie Sanders found in 2014 that 10 generic drugs experienced price increases in just one year ranging from a 420% hike to more than 8,000%.

And then there is the case of patented, brand name drugs where the price begins at astronomical levels. Hepatitis C virus, for example, infects 3-5 million people in the United States and kills over 16,000 annually. In 2013, antivirals were approved by the FDA that successfully treated Hepatitis C 95 percent of the time.

The company Gilead priced its drug, Sofobuvir, at $84,000 for a standard 12 course of therapy. In just 21 months Gilead reported $26.6 billion in sales on its drug, more than 2500 times its costs of research and development, FDA approval, clinical trials, and production.

As Amy Kapczynski and Aaron Kesselheim note in a recent issue of Health Affairs, in India a comparable course of treatment costs $1,000 because of competition unimpeded by long term patent rights. They believe that vigorous completion could eventually drive the price down to $100-250 a treatment, making it widely available.

What can be done? Kapcynski and Kesselheim point to a little-known law, 28 U.S.C. section 1498, that allows the government to exercise its traditional powers of eminent domain by seizing private property for a public purpose, to use patented inventions without permission so long as it pays the patent holder “reasonable and entire compensation.” The federal government has exercised this right before. A profit rate is often set at 10 percent, although courts would likely determine the rate, just as public utility commissions currently determine the profit rate for public utilities, balancing the need to encourage investment while at the same time protecting the public health and the common good.

Sign-up for our monthly Public Good Newsletter and follow ILSR on Twitter and Facebook.