Podcast (buildinglocalpower): Play in new window | Download | Embed Subscribe: RSS

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) implemented the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) in record time. Along the way “they were really thoughtful and intentional about reaching out to US civil rights advocates, representatives, and people that are most connected to the most under-connected communities across the country,” the FCC’s Alejandro Roark explained on this episode of Building Local Power.

ILSR’s Sean Gonsalves added that the ACP is an excellent program to respond to the immediate need of Internet affordability, but some cities are taking the additional step of diagnosing why Internet access is so unaffordable in the first place and prescribing solutions to solve the root problem. Sean highlighted Detroit as a perfect example of this, saying, “[Detroit] understands that the ACP is a great benefit to get folks online right now but they also understand that it doesn’t address the long-term challenge.”

On this episode of Building Local Power, Alejandro Roark, the Chief of Consumer and Governmental Affairs at the FCC, tells a captivating journey of his career from working at the Hispanic Technology and Telecommunications Partnership all the way to his current career at the Federal Communications Commission. He speaks about his LGBTQ inclusion work, racial and economic justice in the telecommunications sector, collective action, and how the ACP is filling an immediate and vital need. Sean Gonsalves, ILSR’s Senior Reporter for the broadband team, weighs in on how to strategize for longer-term Internet solutions that will make our broadband economy more fair and equitable.

“When I think about the digital divide I really try to filter it through the lens of today’s digital divide as an opportunity divide, opportunity in healthcare, economic attainment, and educational attainment. Every aspect of our lives is now sustained and underpinned, and reliant on us being able to connect to the internet.

– Alejandro Roark

“One of the questions that we puzzle over in our program is why is internet subscription so expensive? We think the evidence is overwhelming that it’s because we’ve got a failed market. It’s dominated by monopolies. And when you’re the only ball game in town, there’s not a whole lot of incentive to improve networks, to invest in new networks to expand service, certainly into areas where there isn’t a lot of money to be made.” – Sean Gonsalves

Federal Trade Commission, Affordable Connectivity Program

Federal Trade Commission Consumer Help Center

The White House Affordable Connectivity Program

ILSR’s Broadband Team (Community Networks) ACP Dashboard

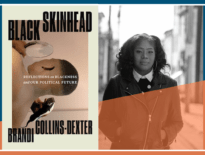

Find these books at your local, independent bookstore:

- Automating Inequality by Virginia Eubanks

- The Master Switch by Tim Wu

- Emergent Strategy by Adrienne Marie Brown

| Alejandro Roark: | When I think about the digital divide, I really try to filter it through the lens of today’s digital divide is an opportunity divide, opportunity in healthcare, in economic attainment, in educational attainment. Every aspect of our lives is now sustained and underpinned and reliant on us being able to connect to the internet. |

| Sean Gonsalves: | One of the questions that we puzzled over in our program is why is internet subscription so expensive? And we think the evidence is overwhelming that it’s because we’ve got a failed market. It’s dominated by monopolies. And when you’re the only ballgame in town, there’s not a whole lot of incentive to improve networks, to invest in new networks, to expand service, certainly into areas where there isn’t a lot of money to be made. |

| Reggie Rucker: | Hello, and welcome to Building Local Power, a podcast from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, dedicated to challenging corporate monopolies and expanding the power of people to shape their own future. I am Reggie Rucker, and today we are welcoming two very special guests to the show, Alejandro Roark and Sean Gonsalves. |

| Alejandro is now serving as the Chief of the Consumer and Governmental Affairs Bureau at the FCC, Federal Communications Commission. This is after having spent a number of years serving as a powerful voice for Latinos in technology and telecommunications policy. | |

| As for Sean, many of our regular listeners may recognize his voice. He is the senior reporter, editor, and communications lead for the Community Broadband Networks Initiative here at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance and recently has done some critical writing and research on the Affordable Connectivity Program, which we’ll get into later in this episode. | |

| But before we jump in, I’m going to throw it to my cohost Luke. Luke, how you doing? | |

| Luke Gannon: | Thanks, Reggie. I am doing great, and I’m looking forward to this conversation. My name is Luke Gannon. And today, we get to learn about what brought Alejandro to the Federal Communications Commission and how he has created a very multidimensional career that works at the intersection of technology, public policy, and civil rights. |

| Then we will discuss a new program, where Sean will jump in, called the Affordable Connectivity Program and how it is helping to bridge the digital divide. Without further ado, we are so excited to have you both on the show today. Welcome. | |

| Alejandro Roark: | Good to be here. |

| Sean Gonsalves: | Thank you for having us. |

| Luke Gannon: | Yeah, of course. Alejandro, I want to start with you. Your career has been really interdisciplinary and multifaceted. I’m curious, what was your spark or the initial drive to work in technology and telecommunications? |

| Alejandro Roark: | Oh, man. It sounds like you looked me up on the internet. Yes, I definitely consider myself first and foremost an accidental activist. I think that my early career, I was doing a lot of LGBT inclusion work. I grew up in the state of Utah. I was born in Mexico City, grew up in Utah, which I think that Utah is misunderstood, right? And I think from the outside looking in, we see LGBT inclusion kind of policy work as a very progressive topic or policy concentration within a, a state that, from the outside looking in, you would think is probably an unfriendly environment. |

| But I think what I really enjoyed and understood about Utah was that, because they have such explicit care community values of, you know, taking care of each other, taking care of your neighbor, they really created a really unique environment where we were able to bring a lot of different stakeholders together, give them a voice and a stake in the solution and the outcome, and then ultimately led to Utah becoming the first state in the country to challenge the constitutionality of a marriage amendment and subsequently passing a statewide workplace and housing nondiscrimination bill. | |

| So I think that is really where a lot of my policy interests and community education and advocacy began. But ultimately, I think that what led me there was the personal interest as someone who himself is gay and really wanted to feel a sense of connection to a broader LGBT and queer community and really kind of understanding that even in my own kind of backyard, there were a lot of opportunities for us to engage, to really, I think, have a meaningful impact and make a difference for not just myself, but a, I think for everybody in the state. | |

| And I think after all the work that we kind of did in Utah, I think to a credit of a lot of wonderful people around the table, and, and that time specifically, I think, to Brandi Balkin, who was the executive director at that time, Utah led the nation in municipal ordinance, nondiscrimination ordinances. Again, we passed this nondiscrimination bill where there was a Republican super majority in both the House and the Senate. | |

| Really, I think what I took away from that is that achieving these, what I consider a shared community win takes collective action. I think, selfishly, I, I was involved because I was personally impacted by the work of the organization, which kind of, kind of began my exploration on the power of one person’s voice, an organization’s voice, and ultimately a community’s voice in shaping the future of a community. | |

| Reggie Rucker: | That’s so incredibly powerful. And you’re a hundred percent right. We did our homework. We did look you up on the internet. And since, uh, we saw that you were the executive director at this Hispanic Technology and Telecommunications Partnership, wanted to get a sense of the work that you were doing there, but how what you just described in terms of the inclusion and the people power and how you packaged all that to the work that you’re doing at HTTP. |

| Alejandro Roark: | Interestingly enough, and I think why I kind of set that foundation as, again, eh, that was such an interesting exercise, where we had also a lot of very progressive champions at the table that were with us on our LGBT inclusion work, but I really kind of made the shift to focus on racial and economic justice. I think during my time [inaudible 00:06:16] Utah, I was really understanding that the segments of our community that are most likely to experience discrimination in their everyday lives are those that live at the margins, right, or at the intersection of both their LGBT identity and their racial identity, the economic that, that’s available to them. |

| And so when I made that shift, um, I realized that there was still a lot of hesitation, even from seemingly very progressive champions, because they didn’t want to get it wrong and I think, because of that, were almost paralyzed to the point of inaction. So at that point, I said, “You know, what I really want to work with a Latino civil rights organization to see is it working someplace else? Is there another state, another place where I think they’re, they really are kind of getting it right, they’re building the necessary support structures to ensure that every person in, in the community, and I think specifically to Black and brown people, historically marginalized communities, have the necessary supports to be successful?” | |

| That’s when I went to go work at LULAC. And LULAC has a long history of leading at the community level to expand opportunity in all forms, specifically for the Latino community. And Brent Wilkes, who was the CEO at the time, really was u, uniquely tuned in to the power that I think access to technology and connectivity has on our community’s ability to participate in a 21st century digital economy. | |

| And so I was working there and kind of working with a lot of our technology partners to where I got the opportunity to really reimagine community programs. How are we scaling and investing and building new interventions? And it became really clear to me that the next frontier for civil and human rights lives in tech and telecommunications policy. | |

| Again, kind of being fortunate enough to work with not just the civil rights community, but internet service providers, tech providers, edge providers, people that were really building the technology and infrastructure, right, they actually came to me and said, “Hey, we really w, think you’d be successful in this role, and we need somebody that could continue to kind of contextualize the impact for the Latino community and also help us all minimize our blind spots, so that we are making more thoughtful dec, policy decisions, to ensure that everybody’s a fully enfranchised member of our digital economy.” | |

| Reggie Rucker: | Actually, if I could just have you expand on that just a little bit, so you mentioned that having access to certain technologies, high speed affordable internet, like, the, having access is going to help people participate in a 21st century economy. Could you say more about just, like, what that means? What does participation look like in this 21st century economy? |

| Alejandro Roark: | The good and the bad of the kind of global pandemic was that I think that it really kind of underscored the critical and essential role that low cost, high quality internet plays in sustaining critical aspects of our everyday life. When I think about the digital divide, I really try to filter it through the lens of today’s digital divide is an opportunity divide, opportunity in healthcare, in economic attainment, in educational attainment. Every aspect of our lives is now sustained and underpinned and reliant on us being able to connect to the internet. It’s no longer this place where we just go to find entertainment. |

| COVID-19 really forced a lot of our federally funded kind of public resources to move online. And the reality is that they’re not moving back to in person, right? A lot of that kind of shift online is going to remain permanent, is going to be built out. I know that for President Biden, he was really clear that it’s time for the federal government to find better ways to modernize the way that the federal government implements a lot of these programs. And what that really means is that more of those are going to be completely reliant or automated in some kind of way. And so we will need internet to even be able to participate, which I think is new to a lot of people and creates a lot of interesting gaps, not just in, one, being able to live in a location where you have internet infrastructure, so that you, your home is serviced, but also do you have the necessary skills to know how to connect, how to stay safe online? | |

| COVID also made every parent across the country have to become their own tech support. Kids now have to learn how to power their laptops or their iPads. Like, this really has been such a, a unique kind of test case. And we have to ensure that we are es, essentially not just connecting people to broadband infrastructure, but I think also connecting people to digital skills training. We need to expand the languages in which these resources are available. We need to ensure that our marketing messages, right, for the way that we market internet service across the country are able to reach those that have been long overlooked or unprioritized, or I think as we now know, and thanks to the infrastructure package, historically unserved and underserved communities. | |

| Luke Gannon: | Yeah. You’ve done a really good job at e, explaining why it’s so critical to have internet connectivity for everyone. I was reading that at the HTTP, you established the Digital Inclusion Alliance, and I’m curious how that transferred over to what you are working on now at the FCC and what your top priorities that you see need to happen to create a more equitable telecommunications sector. |

| Alejandro Roark: | Yeah. I started the Digital Inclusion Summit, ’cause I think the National Digital Inclusion Alliance, shout out to Angela, who is the founder of that, we had a summit. And it was because when I was in a room with tech companies, the number one thing that people would bring to me is, “Well, we don’t know any Black and brown representative voices that can speak to tech policy,” or we hear a lot, “We don’t know any Black and brown engineers that can help us build better products.” |

| And I just got to the point where I realized, “You know what? This is a myth that I think the tech ecosystem tells themself, and it’s myth that I think we hear it so often that we begin to believe ourselves.” So number one was like, okay, I had to do a reality check because even just in my own network, I was like, “You know what? I know incredibly smart, thoughtful lawyers, engineers, tech entrepreneurs. And this is just my own personal network, then I really have to do my part to ensure that we’re getting everybody in a room so that I can say, “Look, if you want to talk to somebody, they’re right here.”” | |

| So again, back to collective action, I, I brought together a lot of my colleagues and counterparts from the civil rights community, members from Asia Americans Justice Advancing Justice, NUL, NAACP, the LULACs of the world, just other people that are really leading and have been at the forefront of leading this digital equity movement and just said, “Let’s create a forum really where we’re focusing and centering the experience of historically marginalized communities and ensure that we are lifting up the leadership of the policy practitioners that are the ones that are knocking on doors, warning us from the beginning like, “Look. If we’re going to have an inclusive future or digital economy, these are the building blocks. The, this is the minimum standard,”” because we’re not even talking about building n, new models or getting too ahead of ourselves. | |

| We’re literally saying, “Look. Number one, have representative voices on your teams. Don’t outsource them. Don’t consult with them. Having a conversation with me is not enough. You need to have people within your organization with the budgets and the structural support to be able to not only make recommendations, but I think build better products,” right? I think you need to have a more consistent and ongoing, robust engagement process so that you are testing your products, checking in with communities about the impact that your products are having. | |

| So I think that really was the ethos for that event, ’cause I think the response was wonderful. Everybody came around the table and I’m, I’m so happy that HTTP has continued to have that program. We also started the Tech Innovadores, which, again, was about recognizing multicultural leadership in tech and telecommunications policy and also happy to kind of see them c, uh, continuing that tradition. That event is happening later in the fall. | |

| So we need to all be our own hype people, right? And we all need to recognize that, if I’m in a room and I’m looking around and I’m the only one that looks like me, brings this kind of middle class upbringing or speaks a different languages, I really got to a point in my career where I was like, “I am not enough.” And I also… we just all need to get in the habit of bringing a friend and asking them to bring a friend, because I can’t be the end all, the be all, end all that’s going to solve everybody’s problems or all of our kind of shared struggles to build, I think, a more equitable future where everybody can connect and create and thrive online. | |

| Luke Gannon: | Of all the ways in which we have a fair amount of work to do, one of them is baseline affordability. How can we get more people to afford this access to high quality internet service? |

| And so one of the programs that were rolled out recently is this Affordable Connectivity Program. Wondering if you could tell us a little bit about sort of the background of that program, what it’s intended to do, and how it’s going so far. | |

| Alejandro Roark: | The Affordable Connectivity Program right now will give you up to $30 a month discount on your internet service. Again, that’s to either establish a new service or help offset a current service that you have. |

| If you happen to live on qualifying tribal lands, you are eligible for $75 a month. And there’s also a $100 discount for a laptop, tablet, or connected device. Those are participating providers are offering that device discount. | |

| And I think it’s important to underscore who is able to qualify. So there really are four ways for your household to qualify for the Affordable Connectivity Program, either based on your household income, if your child or dependent participates in any type of government assistance programs, so think about SNAP, Medicaid, WICC, free or reduced school lunch programs. And maybe you or your child are already receiving the Lifeline Benefit Program, right, where w, where we learned a lot about digital connectivity for cost sensitive consumers. And you could also quality for the ACP through a participating, uh, internet service provider’s existing low income program, right? So those are all. | |

| I think there’s a lot of great ways that make you automatically eligible for the program, which is important. And I think that once we establish the Affordable Connectivity program as a longer term program, we also baked in really important consumer protections. So a lot of the questions that we got were, “What about if I used to have a plan, I wasn’t able to pay it, and now I have a balance, right, or an overdue balance with another provider? Will I have to pay that balance before I can start a new service?” And the answer is no. | |

| We also have a dedicated complaint process. If you struggle either through the application process or receiving your benefit, you can visit FCC.gov/consumer, and there’s a, a tab to click on, Complaint. We read those complaints. | |

| Luke Gannon: | Yeah. I love to hear that the FCC staff does read those complaints. That, I, (laughs), I’m never sure about that. |

| Reggie Rucker: | As an organization seeking the end of corporate control in local communities, you’ll understand why commercial break sounds a little different. There’s no corporation selling you something in an ad, just me, thanking you for listening to our show. And if you’re enjoying this episode, which, if you’ve made it this far, obviously when you are, I definitely encourage you to go check out more of our work to build local power and expand access to fast, reliable, affordable internet at ILSR.org. |

| We’ve discussed today the ACP dashboard that our brilliant team at the Community Broadband Networks Initiative has just released. And this is the type of work that your donations support. So that’s ILSR.org/donate to make a contribution. Any amount is deeply, deeply appreciated. | |

| And if you’re looking for additional ways to support, please rate or leave a review of the show wherever you listen to your podcast. These reviews make a huge difference in helping us reach a wider audience. Okay. That’s a break. Thanks for listening. And now, back to the show. | |

| Alejandro Roark: | Let’s break down some of these myths that we tell ourselves about digital connectivity, specifically about Black and brown people and tribal communities, which are the least likely to have at home internet and why that is. |

| And I think the number one that I qualify as a myth is this idea that, well, Black, brown people, you know, and Native communities, we don’t really understand the value of the internet. And the reality is that there actually has been quite a lot of research that says, number one, we are the most disconnected segments of our collective national community. And when asked about, “What is the primary barrier? Why do you not subscribe to at home internet?,” consistently that barrier was price. It wasn’t that, “I don’t think I need the internet. I don’t want the internet. I really love helping my kids type out their homework essays on a cell phone.” It wasn’t any of that, right? It was price was the primary barrier that prevented cost sensitive consumers, low income households, or really your average household that’s making average household income. I think it’s about $60,000 a year. There’s some interesting intersections there and tabs to that research that actually says that your income level is actually directed correlated to your ability to have consistent at home internet access. | |

| And specifically, it was if you make less than 60,000 a year, if your household makes 60,000 a year, you’re probably not very likely to have at home internet. If you make 50, if your household makes $50,000 a year or less, then you are among the least likely to be able to afford at home internet. And then when you take those numbers and you figure out, “Well, what’s the average household income for a Latino family, for a Black family, for tribal communities?,” and you’ll see, at least for the Latino community, the average household income is like 55,000 a year. So again, that direct correlation about household income and price being their barrier, really something that I tried to get out there and let everybody kind of know and acknowledge and to reset the starting point for the conversation. Congress took action and they said, “Okay. Let’s establish a program that’ll help every household, every family afford the cost of being online.” | |

| Price, I think, is what is really important for everybody to understand and that this program creates a new on ramp to digital connectivity by directly addressing that. I have to give so much kudos to Congress and to the FCC, because the Affordable Connectivity Program started as the Emergency Broadband Benefit Program. To Chairwoman Rosenworcel’s credit and I think to the team of all of our policy advisors, they stood up that program in record time. And along the way, they were really thoughtful and intentional about reaching out to US as civil rights advocates, as representatives, uh, of people that I think are most connected to the most underconnected communities across the country and said, “Look, we have this program. How do we ensure that it works for people? How do we make the enrollment as easy to understand, easy for people to get through?” And so we were at the table from the beginning, because the chairwoman made that a priority. | |

| Luke Gannon: | Sean, I want to throw it to you. So the Broadband Initiative at ILSR has recently released an ACP tracker. And so Sean, can you just briefly describe what that is, what it does? And then I want to look more on the ground. So what city from that have you seen as really succeeding in getting people enrolled, and what city is struggling? |

| Sean Gonsalves: | First of all, let me just say that I agree with Alejandro in terms of the history, in terms of the EBB being this sort of temporary program. And it, with the passage of the infrastructure bill, ACP was established to be a more permanent program in that it’s, it’s a vital program, because, just to put it bluntly, there’s millions of Americans, as Alejandro pointed to, where affordability is the issue. It’s not wanting to be involved and being connected and, and these kind of things. It’s affordability. |

| And so building new networks and the like take time. And certainly, the ACP, I think, is probably the fastest way to get millions of households who find it unaffordable to get an internet subscription at home. It’s the fastest way to get resources in the hands of folks so that they can online, because the need is urgent and building new networks, deploying new networks can take several years. | |

| That’s not to say that we shouldn’t be walking and chewing gum at the same time, which I think the Biden administration and Congress is attempting to do in the passage of the infrastructure bill. You know, obviously, we’ve written quite a bit about, you know, where we have certain critiques about certain aspects of it. But overall, there is this desire to tackle the affordability challenge. | |

| And one city that comes to mind, and I bring it up for a couple of reasons, is Detroit. On our dashboard, the dashboard is very cool. It’s a predicative, iterative dashboard, meaning that you can go to it and find out how many people are enrolled in each state, down to the zip code level. You can find out how much money is being spent in those areas. And I think also what it does when you really dig in, you can also see that there are certain areas that seem to have more success in signing people up than others. And for digital equity advocates out there on the ground, zeroing in on some of those communities, there could be some good lessons to be learned about what particular communities may be doing where you’re seeing higher enrollment rates. | |

| Now, Detroit is one of the… I think our dashboard lists the top 20 or so major metro areas with the highest enrollment numbers, Detroit being one of them. But Detroit is also doing something else that we write about and advocate for in our program all the time. So you have all of these folks who are concerned about affordability. And one of the questions that we puzzled over in our program is why is internet subscription so expensive? And we think the evidence is overwhelming that it’s because we’ve got a failed market. It’s dominated by monopolies. And when you’re the only ballgame in town, there’s not a whole lot of incentive to improve networks, to invest in new networks, to expand service, certainly into areas where there isn’t a lot of money to be made and there isn’t a lot of price competition. | |

| Thankfully, this was something that the Biden administration recognized early on and, in first calling for an infrastructure bill, talked about initially wanting the infrastructure money to really prioritize the deployment of new networks to bring competition to the market, to help lower the barrier of entry for other small and medium sized ISPs to enter the marketplace. | |

| During the sausage making, you know, w, we would have liked that priority to have remained, although the infrastructure bill does specifically say that municipalities and, and county and governments and nonprofits can’t be prohibited from accessing some of those funds to do these things. | |

| And so when I say walk and chew gum at the same time, this is what Detroit’s doing. They understand that the ACP is a great benefit to get folks online right now, but they also understand that, by just doing that, it doesn’t really address the long-term challenge, which is how do you introduce more competition into the market so that you begin to see prices go down? And if you look across the country as we do, where there is competition, prices tend to be quite a bit lower. | |

| And so what Detroit is doing is both. They’re both using the ACP and they’re also building an open access network, meaning that the city is building in a targeted part of the city a fiber network that is open access, which means that the city builds it and owns it and then leases it to private providers as a way of drawing competition and having private providers come in and compete and not have to worry about investing in the infrastructure, but compete on customer service and pricing and so on and so forth. | |

| Detroit is doing something really interesting. A number of cities and communities across the country are taking similar approaches. There’s this period that we’re in that I always call the broadbandification of America, which our guest had referred to earlier about how the pandemic really underscored the essential nature of high speed internet connectivity. | |

| The other thing that our dashboard does, though, and this is, was sort of the genesis for the idea of doing it, is, at its current enrollment rate, how long will it be before the funds are depleted? The infrastructure bill appropriated 14.2 billion for the ACP program. According to our mathematical models, that means that current enrollment rates around 13 or so million folks, which is about one out of three eligible families, so there’s probably about 40 million or so people that might be eligible for this program. And so that’s why there’s this effort to really boost enrollment. But of course, as you boost enrollment, the fund is depleted sooner. According to our model, at current enrollment rates, the funds will be depleted sometime in the beginning of 2025. And if we hit a 50% enrollment rate, which we’re not close to yet, those funds will be a, depleted by November of 2024. | |

| Point being that for digital equity advocates and for those of us who think the ACP program is a very important one, probably sometime right after the midterms is a good time to start lobbying our Congress to think about making sure that those funds are reappropriated so that the ACP program can be sustainable moving forward. | |

| Reggie Rucker: | I want to pick up where you left off with Alejandro. And so as we think about going into the future and the funds being depleted at some point couple years down the road, Alejandro, do you have a good sense of what comes next? |

| Alejandro Roark: | I think that we all understand the essential role that internet connectivity plays in sustaining our lives and into, I think, the economic opportunity that’s available to us. By every indicator, the Affordable Connectivity Program has already been a success. We connected millions of households across the country. |

| But the reality is that there are still many more households that currently live in a place where there is an internet service provider close by and where maybe the cost of affording internet service is still out of reach. And that’s where I think the Affordable Connectivity Program can really help bring those people online. | |

| We’ve reached this incredible milestone through the volunteer efforts of our nationwide network of outreach partners. But the exciting thing is that Congress also allowed the FCC, the Federal Communications Commission, with the ability to establish its very first grant program. And so this grant program, which was formally established as a part of our August open meeting, will allow us to be doing targeted investment to help communities scale their own kind of outreach efforts to ensure that we’re reaching deeper into community, that we’re continuing to innovate and create new public engagement strategies so that every person knows about the program and every person that is interested in signing up for the program has the wraparound support that they need. | |

| If we’re really, truly trying to reach households that don’t yet have any type of connectivity, then they need help enrolling in the program, they need help understanding what are their local internet service providers and which one might have option that works best for them, and they also need help figuring out what is the plan that fits my family’s needs and my long-term budget? | |

| Luke Gannon: | Before we start to close out here, I just want to take a step back and go to you again, Sean. I’m thinking about the necessary steps to make internet accessible and affordable for all. And Sean, you talked about competition. But I’m wondering how do we make that possible, whether it’s, you know, at the local, state, or federal level? What policy choices or what do we need to do to have a more competitive market in this sector? |

| Sean Gonsalves: | That’s a great question. Bringing competition requires a number of things. One, it means being aware of the states that don’t allow for municipal broadband or have barriers to it, because we see that municipal broadband networks, where they operate, tend to lead to faster speeds, lower prices. And we’re talking about, when we saw municipal broadband, we’re talking about publicly owned, locally controlled networks. |

| And I think by advocating for policies that support that, as you’re seeing in the state of Vermont, as you’re seeing in Maine, as you’re seeing in Baltimore, communities are now realizing that they actually have the power to solve the digital divide within their borders, within their communities, with the help of federal and state grants. There’s numerous programs that are available. But I think overall, we are in a moment where planning is key and knowing that there are communities who are marshaling not only federal and state resources, but local resources and local know-how, because after all, it’s local communities that have the best sense of where the connectivity challenges really lie in the community. | |

| When suddenly kids have to go to school online overnight, that local community finds out pretty quick where the pockets in the community are where internet access is a real challenge. There’s, you know, an array of models, public-private partnerships, open access networks, community broadband approach. But again, there’s also partnerships with a multitude of private providers. So it’s a really a all of the above needs to be considered in terms of addressing access, adoption, and affordability, those three As. Access has more to do with infrastructure. Adoption has a lot to do with s, around skills, and it’s linked to affordability. | |

| But we need to be looking at all three of those areas, access, affordability, and adoption, and bringing all of our resources to bear. And the thing that’s so exciting about this particular time period is that f, for the first time in, in decades, the federal government is really putting a serious effort into tackling this challenge. | |

| Reggie Rucker: | Before we close it out, we always like to do this question. We have a very s, soft spot in our hearts for the local book stores. So this is the question that shows some love for the local book stores. And we’ll go to you first, Alejandro. What is the book that you’ve read recently or in your life that has really impacted the way that you approach the work that you do or even sort of choose to do the work that you do? |

| Alejandro Roark: | One of the, I think, most well-articulated, easy reads that has really informed the way that I think about my work, especially within the federal government, it’s called Automating Inequality by Virginia Eubanks. And she basically takes the whole book and does a lot of different case studies about how, as we’ve automated or digitized a lot of the federal government programs, we can maybe inadvertently be baking in some of the biases or knowledge gaps of the past and what kind of questions we need to be critical and ensuring that we are asking of policymakers, decision makers, and program implementers so that we can ensure that we are course correcting those unfortunate, I think, past decisions that were made without our input, so that we can achieve a future where, again, everybody can connect, can create, and can thrive online. Definitely worth a read. |

| Sean Gonsalves: | That’s terrific. Noted. Noted. I’m a big reader. Let’s see. Well, two books come to mind, really. One’s specifically about telecommunications, but Tim Wu’s The Master Switch is a classic. I mean, it’s well-written. It really provides a really insightful look at the history of telecommunication in the United States and policy and sort of answers the, “How did we get here?” question. So that book is excellent, super accessible. And Tim Wu actually has served, and I think he may still be there, but as an advisor in the White House on some of these issues. So a good person to have inside the tent working on policy and really somebody who’s thought really deeply and thoughtfully about some of these issues. |

| And then more recently, I came across a book called Emergent Strategy by Adrienne Maree Brown, which is pretty cool. At first, it was like, “Oh, this book is kind of different, the way it’s presented and what have you.” But it sort of, to my mind, raises this question, kind of emergent strategies, what if we could mimic essentially the way nature works in terms of, like, flocks or birds et cetera and, and working in concert and coordinating? And how can we create organizations and movements even that reflect that kind of authentic, democratic kind of movement where, you know, you’ve got a flock of birds and they all somehow know what direction to fly and when to turn and what positions to take and things of that nature. So that’s another fascinating book. Those are two that come to the top of my mind (laughs). | |

| Luke Gannon: | Those both sound really good. I’m very interested in Emergent Strategy. Thank you for that recommendation. So that is it for the show. Thank you both so much for being on. We so appreciate all of your words, and I think this is such an important conversation. So I’m excited to get it out into the world. |

| Alejandro Roark: | Wonderful. Thank you for having me. And Sean, next time, I want to hear about your early career. I feel like I was through the hot seat, but I want to learn all about you. |

| Sean Gonsalves: | (laughs). |

| Alejandro Roark: | You’re an interesting guy, and I really appreciate your research. |

| Reggie Rucker: | All right. What a great conversation. Thank you for tuning into this episode of the Building Local Power podcast from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. You can find links to everything discussed today by going to ILSR.org and finding Building Local Power under the podcast tab. And there, you’ll find the show page for this episode. That is ILSR.org. |

| Luke Gannon: | A final big, big thank you to Alejandro Roark and Sean Gonsalves for joining us on Building Local Power. The FCC and ILSR Broadband team are here to help. So head over to ILSR.org and check out additional resources in the show notes for this podcast, including more information about the Affordable Connectivity Program and ILSR’s ACP dashboard. |

| Have you heard about our newsletters? Go sign up to get updated on all of our recent research? And please, follow us on Twitter at ILSR. We post every day on new reports, podcasts, and resources for all of us to better understand the importance of building local power. We would love to hear your feedback, so please leave a review on our podcast channels. | |

| Our theme music is Funk Interlude by Dysfunction Al. And finally, a shout out to Drew Bursbach, who edits this podcast. This is Building Local Power. |

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

Like this episode? Please help us reach a wider audience by rating Building Local Power on Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts. And please become a subscriber! If you missed our previous episodes make sure to bookmark our Building Local Power Podcast Homepage.

If you have show ideas or comments, please email us at info@ilsr.org. Also, join the conversation by talking about #BuildingLocalPower on Twitter and Facebook!

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | RSS

Audio Credit: Funk Interlude by Dysfunction_AL Ft: Fourstones – Scomber (Bonus Track). Copyright 2016 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial (3.0) license.

Photo Credit: Worcester Youth Collaboratives

Follow the Institute for Local Self-Reliance on Twitter and Facebook and, for monthly updates on our work, sign-up for our ILSR general newsletter.