When Ariel Zaurov first opened his pharmacy in downtown Jersey City’s Paulus Hook neighborhood, in 2005, he was one of just a few businesses in the area. It was a tough start — there weren’t a lot of people who lived in the neighborhood, and the store, called Downtown Pharmacy, didn’t get much foot traffic — but Zaurov dug in, joining the board of the neighborhood association, donating to school groups, and working with local vendors.

Now, 12 years later, Zaurov has opened a second location that’s one stop away on the light rail, and he employs 20 people full-time at both locations. The Paulus Hook neighborhood is thriving, too, with a growing population, increased development, and new businesses, many of which are independent. “Most places are run by the people who own them,” says Zaurov.

As the neighborhood has grown, chain stores have also become more interested in it. In early 2017, CVS signed a lease for a 20,000-square-foot location two blocks up the street from Zaurov’s pharmacy.

It’s a familiar story, one that plays out in cities across the U.S.: Independent business owners sink roots into a place, meet community needs, and foster neighborhood growth, and then, as the area becomes vibrant, chain stores sweep in to open their own locations.

What’s different about the story in Jersey City is that there, the city has taken proactive steps to check this common cycle, and instead, build a model that allows for more opportunity for local entrepreneurs.

As the Paulus Hook neighborhood grew, Candice Osborne, who lives in the neighborhood and also represents it on the Jersey City Council, saw two things starting to happen. On the one hand, some of the real estate developers who were increasingly drawn to the neighborhood had what Osborne describes as “a little bit of vision,” and were interested in being part of fostering a walkable, livable community. Some developers were willing to work with local business owners to fill the ground-level spaces in their new projects, Osborne says.

On the other hand, Osborne saw some developers who weren’t interested in the street-level side of their projects at all. “We require ground-level retail, but developers would prefer to build apartments,” Osborne explains. “So there were some developers just letting space sit, and waiting for a big-box that can sign a 20-year lease with a high degree of certainty.”

Osborne wanted to come up with a tool the city could use to encourage the developers that were working with local businesses, and also “force the guys that were sitting empty to do something,” she says. “We have a situation where we have all of these great small businesses and we want to make sure they don’t get pushed out,” says Osborne. “That it wasn’t just a 10-year cycle of opportunity.”

In early 2015, Osborne introduced a policy to amend the city’s land development code, and in May of that year, the City Council passed it. The ordinance restricts formula businesses — i.e., chains — in parts of the downtown area of the city, limiting them to a maximum of 30 percent of ground floor commercial area on any single lot. The restriction applies to retailers, restaurants, bars, and banks, and includes an exception for grocery stores.

“Jersey City Municipal Council has determined that formula business… may detract from downtown Jersey City’s unique community character,” the ordinance reads, adding that the downtown also “supports a great variety of unique local businesses.” The amendment is necessary, the ordinance continues, “in order to preserve downtown’s distinctive sense of place and unique neighborhood character.”

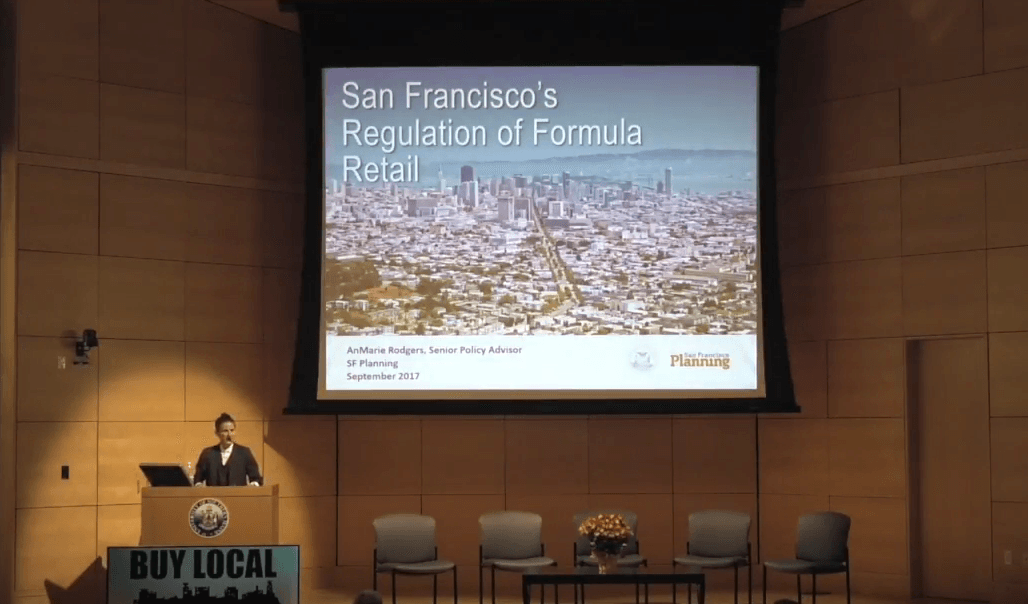

Jersey City isn’t alone in taking this type of policy action, which is known as a formula business restriction or, sometimes, a commercial diversity ordinance. Cities across the country, from Fredericksburg, Texas, to Port Townsend, Wash., to Chesapeake City, Md., have adopted ordinances that cap the total number of formula businesses, prohibit them entirely, or require that they meet certain conditions to open. In San Francisco, a version of the law passed in 2004 has proved so successful and popular that the city expanded and strengthened it in 2006 and again in 2014.

(For more about San Francisco’s formula business ordinance, see our article, “How San Francisco is Dealing With Chains,” watch this recent talk from a San Francisco city planner, or listen to our recent podcast episode).

These laws have proven durable and popular, and have even gained acceptance among developers. In Jersey City, however, CVS has spent the last eight months first ignoring the law, and then pressuring the city to abandon it.

When CVS signed its new lease earlier this year, the location and size meant that it was in violation of the formula business ordinance. In response, the city denied CVS’s certificate of occupancy. Despite the fact that similar laws have consistently been upheld by courts, CVS threatened to sue the city. Three weeks later, the mayor proposed repealing the ordinance.

By June, the ordinance was back before the Jersey City Council. But an interesting thing happened: Two years after initially passing the law, the City Council voted 8-1 to keep it, the Jersey Journal reported, despite the mayor’s support for repeal. That tally included a flipped vote from one council member who had voted against the ordinance back in 2015, but this time, voted in support of it.

To an onlooker, it could seem as though, through the ordinance, the city is taking sides in the market. In fact, though, this is the kind of function that cities perform all the time. Like other land use ordinances, Jersey City’s law is about guiding development in a way that considers the public interest. The formula business ordinance doesn’t prohibit CVS from opening, but it does require that it do so at a scale that’s appropriate to the neighborhood; one of the largest existing businesses in Paulus Hook, a grocery store, is a mere 6,000 square feet, or less than one-third the size of CVS’s proposed location.

This kind of measure also has secondary benefits. It works as a mechanism cities can use to give independent businesses a fair shot to compete. By virtue of its market power, CVS brings a lot of advantages to its competition with local businesses. Many of these advantages don’t relate to the quality or cost of its service or the preferences of consumers. CVS, for example, owns one of the largest of the companies that manage prescription benefits and pharmacy reimbursements on behalf of insurers. It uses this relationship to squeeze independent pharmacies behind the scenes — and also to keep drug prices high and limit choices for customers.

Zaurov, of Downtown Pharmacy, doesn’t mind competition. He already faces lots of it: There are several other independent pharmacies in downtown Jersey City, including one just up the block from him. And two existing CVS locations are about a 15-minute trip away on the light rail. But he does chafe at what he perceives as unfair tactics. “I’m all for fairness and competition,” says Zaurov. “But CVS has ways that they do not play fairly.”

“We can’t really fight the problems with the reimbursement process,” he adds. “But what we can do is be really involved pharmacists, where patients come in and feel that we know them and know what they need.”

Jersey City benefits from the presence of businesses like Zaurov’s. From his community involvement, to his local payroll, to his relationships with his customers, Zaurov is deeply connected with the city. Research shows that these roots have tangible benefits, and that places with more locally owned businesses are also more equitable, prosperous, and connected. A formula business policy is one way that cities can reflect these benefits in their zoning codes and help foster an environment in which independent businesses have a fair shot at succeeding.

Despite the city council’s vote to keep the ordinance, for now, CVS appears to be continuing its effort to overturn it. In November, a local election changed the makeup of the Jersey City Council, which could impact the ordinance. There remains the threat of a legal challenge, too. In other cities and states, properly written formula business ordinances have been upheld by courts, but the prospect of a legal battle with a large national company can have a chilling effect for cities.

“The battle is won,” says Zaurov. “But the war is still questionable.”