When school shut down past spring, Unit 4 schools in Champaign, Illinois scrambled to get students connected like everyone else. The district handed out Chromebooks and teachers went to work transitioning to online instruction so the school year could continue. But the district noticed that a large percentage of its students weren’t logging on and the bulk of them came from Shadowwood mobile home park, where although fiber ran up and down every street in the neighborhood only one family subscribed to wireline Internet access. So Mark Toalson, the city’s IT Director, began making calls, and by the end of the summer a coalition came together to build Shadowwood’s students a free fixed wireless network which went online in August.

Fiber Just a Few Feet Away

The mobile home park sits on the north side of the town of 90,000, and is largely populated by Hispanic residents. Roughly 250 students who attend the Unit 4 school district live there, and according to Toalson not a single one had Internet access beyond personal mobile phones before they began last spring. In late May Mayor Deborah Feinen asked the city manager what could be done, and Toalson was asked to take on the project.

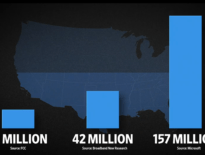

Local circumstances make the Shadowwood Mobile Home Park a perfect case study in how efforts to bridge the digital divide need to tackle every facet of broadband gap to be successful. A $29 million grant in 2010 to bring Fiber-to-the-Home to the Urbana-Champaign-Savoy area meant that neighborhood had the infrastructure, but almost no one could afford the last-mile connection because of the high upfront costs. “We have fiber up and down every street in this trailer park, but they simply can’t afford to hook up to it,” city of Champaign Director of Information Technology Mark Toalson remarked in an interview. i3 Broadband, which owns and operates the infrastructure, normally costs $56/month (both in Shadowwood and without) and has been offering a $30 discount during the pandemic. It’s a generous move, but moot for families who can’t pay to connect to the infrastructure sitting just below the street, a handful of steps away. So most of Shadowwood’s residents went without.

By early June, Toalson had collected the group that would facilitate the deployment of a fixed wireless network capable of reaching every mobile home in the park. Funds came from Urbana-Champaign Big Broadband (UC2B), a nonprofit which enables fiber deployment to the Urbana-Champaign area. i3 broadband supplied the backhaul and has promised not to charge for ongoing access so long as it’s being used for schoolwork, and local startup and hardware manufacturer Mesh++ provided the routers which beam the signal into resident’s homes.

$20,000 in funds were available for the project, and almost every participant chipped in something extra to make it work. $14,650 went to equipment to Mesh++, who (although they normally operate as a hardware supplier only) went onsite and installed the equipment. They also gave the school a service package running on top of the network which can provide reports about usage and outages. i3 only charged for equipment required to hook up to the backbone — around $3,000 —and have committed to keeping its backhaul services free going forward as long as the network’s being used for students. Power company Ameren Illinois expedited its pole permitting process, and is charging an annual pole usage fee of $800. It’s is also charging an estimated $26 month per pole for power. The network went live in the middle of August, allowing students to connect via their school-provided Chromebooks and access coursework using school credentials. At the moment, it’s not open for families or usage outside of the school content and course delivery.

The Shadowwood wireless network infrastructure is made up of six hardwired routers sitting on power and light poles throughout the park, which pass the signal onto five additional solar-powered routers acting as extenders and repeaters. Hardware for the network was supposed to by owned by UC2B, but in light of restrictions on their ability to enter usage agreements with Ameren, they instead granted the money to the school district, which in turns owns the assets.

Both Mark Toalson and Lee Tenant, Vice President of Operations for Mesh++, report that the network is operating well in its first month. Each router can handle 350 Megabits per second (Mbps) of throughput, and the network was designed for 122 concurrent users. Each connection is capped at 10Mbps symmetrical to provide enough bandwidth for videoconferencing for each student. So far, the Shadowwood network has seen as many as 75 concurrent logins without any major hiccups, and real-world speeds for students as the network has gone online are running 8/4Mbps for those with Chromebooks and 36/8Mpbs for PC users. Some Chromebook users experienced latency issues initially, which are being worked out with Mesh++.

We talk about infrastructure so much . . . but there are also a lot of families that have the infrastructure available, but that doesn’t mean they have access to it. So being able to create community systems is important to us. — Lee Tenant, Vice President of Operations, Mesh++

Overcoming Obstacles

Both Toalson and Tennant recalled that the network deployment went relatively smoothly, with all parties working together to resolve issues quickly and efficiently. Hiccups along the way included getting power access on the Ameren poles for six of the routers — because of company regulations regarding unmetered 12v access and on-pole connections, the city electrician designed a closed breaker box on site to get routers hooked up. According to Tenant, aside from working with the school to make sure the network integrated properly with the school’s authentication servers, there were no problems after the routers were connected.

A Model for Others

Part of the reason this project succeeded is that Shadowwood houses a large group of unconnected students all living in relatively close proximity. The walls of the mobile homes are thin too, which allows Wi-Fi to penetrate more easily than in the heavier construction of multi-dwelling units (MDUs). It also worked because fiber infrastructure (owned by i3—which was just purchased by Wren House Infrastructure) was already there, just waiting to be used.

A similar project is underway in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where the city is targeting eight mobile home parks in two city council districts. It will use a single transmitter at the New Mexico Law Enforcement Academy aimed at additional antennas scattered within the neighborhoods to deliver free public Wi-Fi to a little less than 2,000 homes once complete.

Shadowwood’s network can’t be used by families, making it more similar to the school-based LTE one being done by San Antonio, Texas, than the community network just completed in San Rafael, California. The city would like to open the network up for free usage by everyone in the house, but at the moment its priority remains getting students connected for the current school year. The IT department is in talks with the school district about a couple of apartment buildings with unconnected clusters of students where a similar deployment may take place. Champaign Mayor Deborah Frank Feinen said when the project went live in August:

Helping bridge the digital divide by providing free Internet service to our underserved students to facilitate distance learning has never been more important than it is right now. I applaud everyone who quickly pulled together to make this project possible and wish all our students the very best as we kickoff a very unique school year.

Featured image by Wikimedia Commons user Dori, used under a Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

This article was originally published on ILSR’s MuniNetworks.org. Read the original here.