ILSR is on the steering committee of the Public Power Project, an initiative to better understand publicly owned electric utilities in the Midwest. The following is a reflection by Jackson Koeppel, an energy democracy practitioner and consultant and a lead staff member of the Public Power Project, alongside Erik McCleary and Colin Byers.

In early December, Erik and I traveled down to Cleveland for the first round of interviews for the Public Power Project.

For those unfamiliar, the goal of the project is to better understand how to achieve equity in publicly owned electric utilities — both those that currently exist and those imagined by municipalization campaigns across the country. To do this, we’re interviewing communities and public officials where public power already exists and where it is emerging to understand how different stakeholders consider the equity issue and where they align or diverge.

In this first trip, we spoke to numerous advocates engaged with the significant failures of Cleveland Public Power to meet reliability and affordability standards, as well as the staff of a newly formed Cuyahoga County utility. There was terrific richness in these interviews, which we expect to reflect more deeply in a forthcoming report. For those who want to follow along, here’s a few of the big insights that emerged.

Cleveland Public Power (CPP) is struggling with a legacy of bad decisions and poor leadership. CPP charges higher rates than other Ohio utilities and has had a history of poor engagement with concerned community members. It goes back to some big, long-term deals CPP made with American Municipal Power (AMP) to own shares of coal plants and hydro plants, contracts which are proving extremely costly. Advocates point to failures of leadership at the time these contracts were executed, and the tenuousness of small utilities like CPP in that the wrong leadership at the wrong moment can create major long-term issues. CPP primarily serves East Cleveland, predominantly Black and low-income, which means that its poor performance compared to its peers is also an issue of racial and economic justice. This history raises questions of how to protect new municipal utilities from making the same mistakes, and holding historic public power institutions accountable when they occur.

There’s a lot of faith in public ownership despite CPP’s failings. Advocates with strong critique of CPP still expressed heavy critique of FirstEnergy and the investor-owned monopoly model writ large. In a state with major corruption scandals and an IOU exerting terrific pressure on the political system, there is still an association with the potential of CPP and public power as a tool to retain local, democratic control and do more interesting things than the big utilities allow, when there is strong and effective accountability coming from the grassroots.

Ohio’s famously corrupt investor-owned utility, FirstEnergy, has a significant part to play in CPP’s deficiency. On paper, CPP isn’t stacking up to FirstEnergy on performance. But we learned that a big part of the “why” there is directly related to FirstEnergy’s own behavior. CPP only serves around 70,000 meters and has been redlined into serving low-income neighborhoods, with little margin for error, as a result of FirstEnergy being allowed to directly compete for their customers. Since the early 80s, FirstEnergy systematically poached Cleveland’s large energy users and upper-income neighborhoods, while running marketing and political campaigns to erode CPP’s public image. As a result, CPP is continually bleeding customers and struggling to provide quality service as its resources to do so dwindle.

Institutions for progressive public power don’t seem to exist, and are sorely needed. The new Cuyahoga County municipal utility emerged from the County sustainability department leadership being unable to move projects forward meaningfully with CPP or with FirstEnergy. Equity and community governance are not top-of-mind for the project leadership, who are still working to get their first projects built. This new utility and CPP lack any kind of association of public power providers rooted in equity goals. Advocates and officials alike raised the need for peer connections, models to learn from, and ways to escape the razor-thin margins on which small projects or utilities live and die. One topic to continue exploring is what a truly progressive public power association would look like. Would it help local utilities to advocate for their rights to access the transmission grid to source clean energy? Would it organize bulk power purchases? Would it provide peer learning, shared technical resources, political advocacy? How would it be funded and made sustainable? Whatever the answers, it seems they’re questions worth asking.

The story of Cleveland Public Power indicates that achieving equitable public power will require strong grassroots organization, institutions of support to new and existing municipal utilities, and protections against IOU interference. We’re looking forward to seeing what new insights emerge as we go into interviews with campaigns for new municipal utilities and existing public power all around the Midwest!

Jackson Koeppel

This article originally posted at ilsr.org. For timely updates, follow John Farrell on Twitter, our energy work on Facebook, or sign up to get the Energy Democracy weekly update.

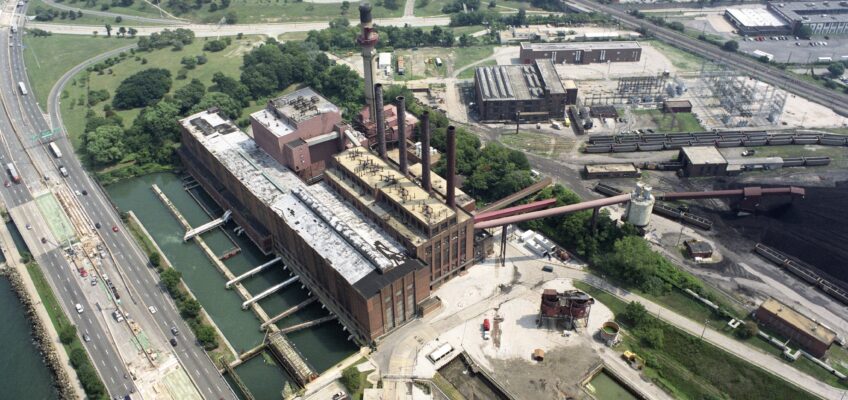

Featured photo credit: FirstEnergy Corp via Flickr (CC BY ND 2.0)