Podcast (localenergyrules): Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Electric cooperatives arose from New Deal legislation that provided government-backed low-interest loans to bring electricity to rural areas that for-profit companies wouldn’t serve in the 1930s. They were engines of the rural economy. But today they face unique challenges, including a disproportionate reliance on coal-fired power, often purchased on decades-long contracts. Additionally, even though rural coops serve 90% of counties with persistent poverty, member engagement has declined precipitously from the golden years, and now few cooperative members even realize they are owners of their electric company.This week Ed Marston, former board member of the Delta-Montrose Electric Association in western Colorado, joins John Farrell on Local Energy Rules to talk about the electric cooperative world. He highlights the good, the bad, and what his and other cooperatives are doing to spur clean energy investment in a region that so desperately needs local economic development.

The Big Picture

Ed Marston (pictured left) has worn a few hats in his lifetime. He was publisher for High Country News, a (really good) environmental magazine for the Western U.S. He holds a doctoral degree in experimental physics. He’s the Chairperson of the board of directors at Solar Energy International, a nonprofit dedicated to training people in renewable energy.

But he was also the first “hippie” (his own words) to join the board of directors for the Delta-Montrose Electric Association in 1983. He served for 18 years, lobbying against new coal plants and rate increases while seeing a lot of change come to the electric cooperative’s two-county service territory in western Colorado.

Most recently, the counties’ economic base of coal mining has taken a hit. Amid industry-wide losses, 800 of 1000 underground mining jobs have vanished. As with many other cooperatives suffering economic losses, they’re struggling to make up for the lost electricity sales and local employment.

“Think of the rural electric coops as zombies,” says Marston. “Think of them as the walking dead.” Around the 1950s, most electric cooperatives still bought electricity from investor-owned utilities. To control their own destiny, they formed generation and transmission cooperatives, or “G&Ts.”

The G&Ts became giants, a “billion dollars” to its member cooperatives’ “million dollars.” They built coal-fired power plants almost exclusively. They invested in coal mines. They stretched long power lines across the country, connecting member cooperatives together. And though the G&T was supposed to be a “cooperative of cooperatives,” the relationship became more paternalistic over time.

“The rural electric co-ops are willing participants in this lord-serf relationship,” says Marston. The legal instrument that cements it all together, he continues, is a partial-requirements contract. (These are known as all-requirements contracts if the member cooperative must purchase all of its energy requirements from the G&T.) Delta-Montrose’s contract requires the co-op to buy 95% or more of its electricity from its G&T, Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association.

These contracts become like the roach motel — “you can check in, you can’t check out,” says Marston. When Tri-State came to its “serfs” for a contract extension in 2004, Delta-Montrose said no, allowing them to exit in 2040 (the co-ops that re-signed can’t leave until 2050). Some cooperatives even objected that the chains of these long-term contracts violated federal antitrust law meant to skewer monopoly power.

While Tri-State pushes for uneconomic projects (such as a $2.8 billion coal plant getting approved the day before the Clean Power Plan was announced), its member cooperatives must take out tens of millions of dollars of debt to cover the project costs. Before, “bigger was better,” says Marston, but today “bigger is more costly.” These power plants are in danger of becoming deadweight, or “stranded assets” in utility-speak, as rising coal prices, regulations to ensure clean air and water, and cheaper renewable energy make their operation more costly.

What Streams Might Come

For years, Delta-Montrose has suggested that there might be another path: building out local energy resources while using load management and energy efficiency to reduce energy demand. Gradually, the electric cooperatives under Tri-State could begin to grow grassroots energy at what has been, historically, a top-down organization.

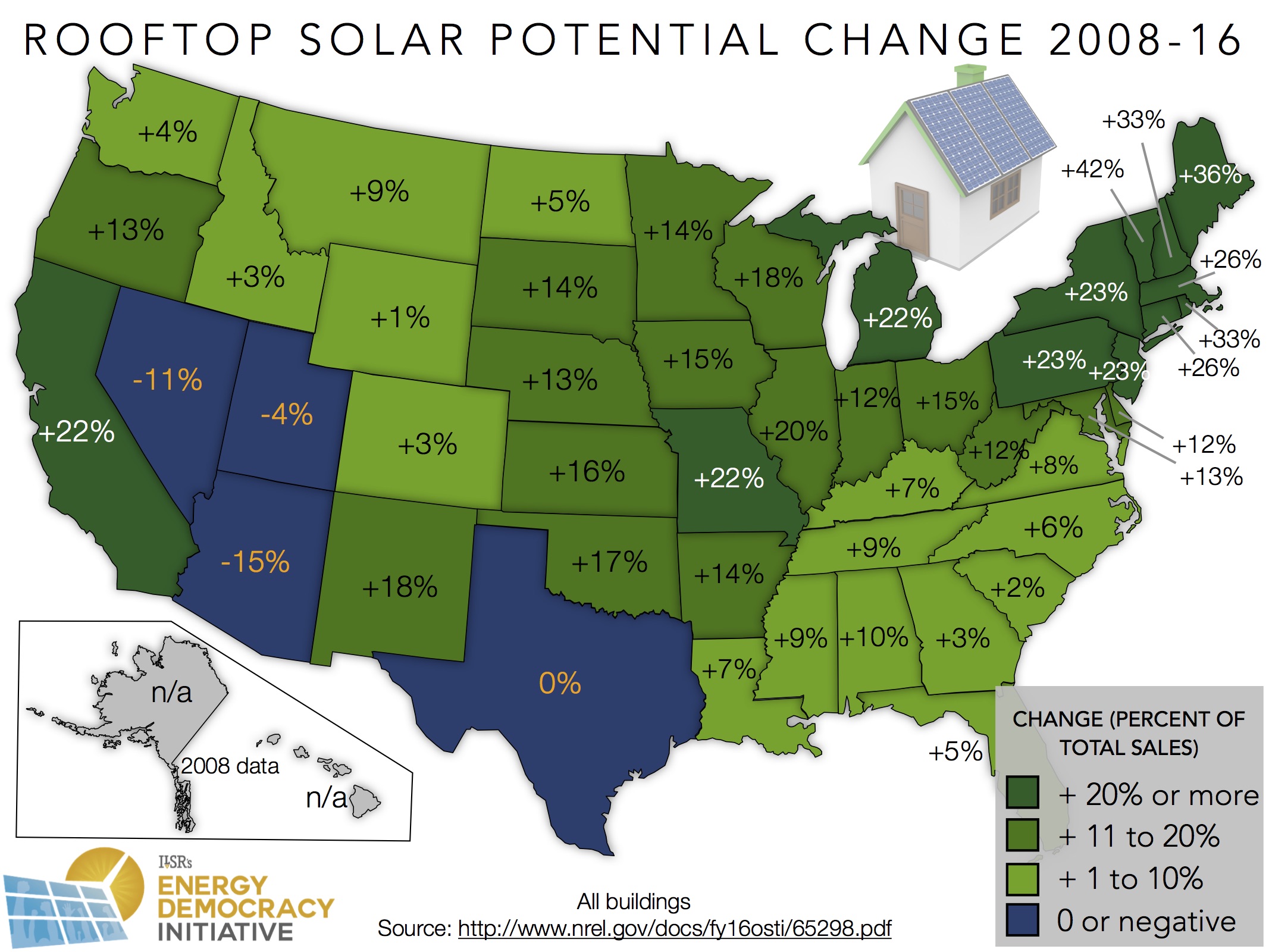

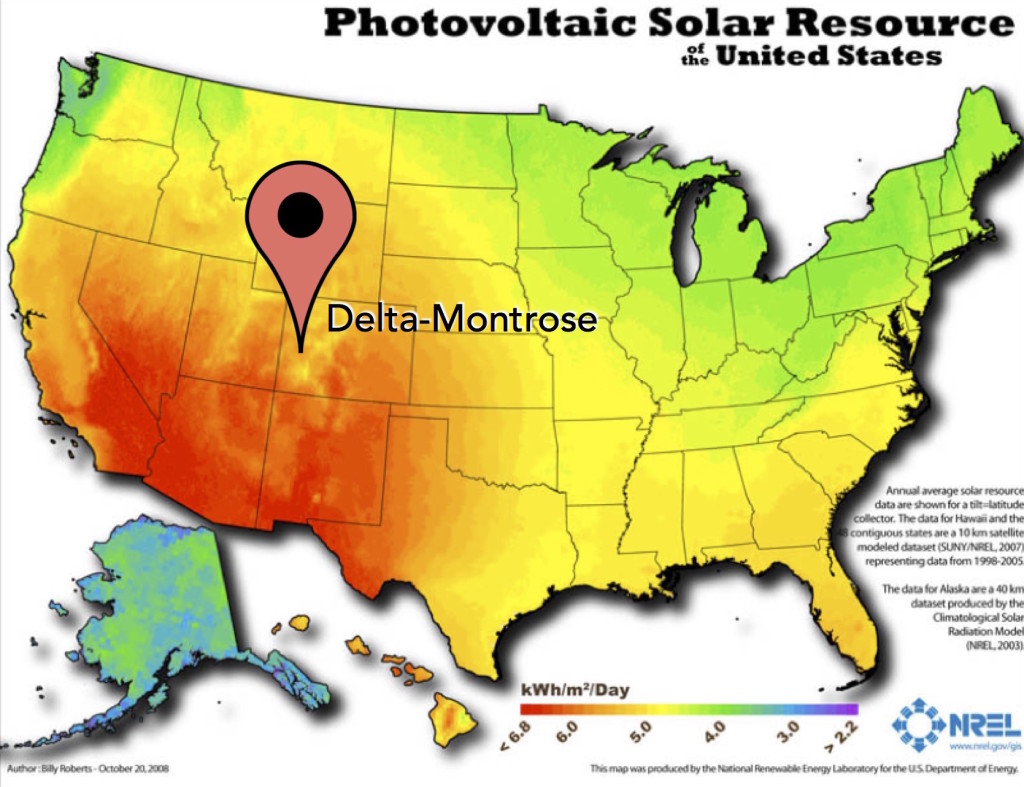

Like other regional cooperatives, Delta-Montrose isn’t without the resources. Its local, abandoned coal mines leak enough methane to provide as much as 30 megawatts of power (30% of the cooperative’s sales). Its dead forests, battling invasive beetles, could be harvested for biomass. Mountain streams run miles from mountains to valleys, providing potential for hydroelectricity. And of course, it’s sunny in western Colorado and Paonia is home to Solar Energy International, which could train workers to install solar. In all, another Delta-Montrose board member predicts the cooperative could generate 50% of its energy from local, renewable sources by 2025.

Last year, after a Delta-Montrose petition, the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission decided that PURPA requirements trumped Delta-Montrose’s 5% self-generation limit. Meaning: “It appears that the FERC ruling allows us to generate 100% locally,” says Marston.

The legalities of the ruling are being tested right now, with Tri-State appealing FERC to allow it to impose a “rate penalty” on DMEA and other co-ops that go past the 5% limit, and Delta-Montrose narrowing in on a contract that will take it above the self-generation limits. It’s part of a history of “bully boy” tactics, says Marston, and the latest in a string of incidents causing him to say, “Tri State is a law firm with a few power plants attached.”

Of course, if the court battles get too messy, Delta-Montrose could always buy its contract out, as the Kit Carson Electric Cooperative in New Mexico has done with Tri-State.

Electric cooperatives today find themselves in a bind. Distributed energy is becoming cheaper than centralized energy. Utility managers have to worry about losing electric sales and meters. The G&Ts continue to invest in coal and fossil fuels, while lobbying against climate regulation and clean energy rules. Electric cooperatives span three-quarters of the land, serving 12% of the population, in many of the country’s poorest areas. “We are Red America,” says Marston.

Delta-Montrose, though, sees opportunity. It is stringing fiber optic to every home and business in its territory. And now, with the FERC ruling, its sees an opportunity now to reinvigorate its economy with clean energy investments, while turning its electric service into something more humane.

For more information on the challenges of re-inventing electric cooperatives in the 21st century, see ILSR’s report Re-Member-ing the Electric Cooperative, released in March 2016.

This is the 33rd edition of Local Energy Rules, an ILSR podcast with Director of Democratic Energy John Farrell that shares powerful stories of successful local renewable energy and exposes the policy and practical barriers to its expansion. Other than his immediate family, the audience is primarily researchers, grassroots organizers, and grasstops policy wonks who want vivid examples of how local renewable energy can power local economies.

It is published intermittently on ilsr.org, but you can Click to subscribe to the podcast: iTunes or RSS/XML

This article originally posted at ilsr.org. For timely updates, follow John Farrell on Twitter or get the Energy Democracy weekly update.

Image Credit: John Fowler from Wikimedia Commons via CC BY-SA 2.0