The Enron scandal in 2002 created California’s energy crisis and left the state in a tailspin from rolling blackouts and sky-high electricity prices. To prevent future energy shortages, California required home hook-ups to gas infrastructure. Now, these policies are effectively forcing reliance on gas. Although California’s building codes make electrification difficult, gas dependence affects communities across the United States. Nine in ten homes in California use gas, while three in four homes nationwide use gas for heating and cooking. However, with prices for clean energy technologies decreasing, electrification has become more accessible and cheaper than gas hook-ups. For cities across the U.S., leaders aim to kick gas reliance to the curb.

In July of 2019, Berkley, Calif. became the first U.S. city to ban gas hookups to most new buildings in an effort to achieve greenhouse gas reduction goals. After six months of an intensive outreach campaign, the ban faced little opposition. The public and the utility, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), showed up to support the reach code. Berkley’s ban on gas hookups to new, multi-family units began on January 1st, 2020, and will expand to other new construction when state legislators finish new standards for all-electric buildings.

Since the passing of Berkley’s ban on new gas hookups, 28 California cities passed similar gas-free or building electrification reach codes. 50 other California cities, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Sacramento are considering similar policies. In some states, reach codes allow cities to set local building energy codes that go beyond state minimum requirements for energy efficiency in buildings. Cities and counties in California must file their reach codes with the California Energy Commission before they can go into effect. In states without reach codes, city ordinances and town bylaws allow local governments to set higher energy efficiency standards. Although not every bylaw, ordinance, or reach code is as strict as Berkeley’s, they all want to experience the economic and health benefits of moving away from gas.

The bans bring some opposition (such as chefs concerned about cooking without gas), but also some additional benefits (to health and safety).

Cooking

The most significant resistance to the Berkeley gas ban is about cooking. Restaurant industry interests argue that, without gas, flame seared meats and charred vegetables will be rare, and as a result, chefs would need to be retrained to use different cooking methods. Opponents take advantage of Americans’ lack of familiarity with electric induction cooking, an efficient alternative to gas and electric resistance with pinpoint control. Many professional chefs are beginning to prefer electric cooking because it offers more control, with a majority of European chefs already using induction stoves. Although induction cooktops are slightly more expensive than gas ranges, professional chefs say they are comparable in performance to gas. The Culinary Institute of America is even training chefs on both gas and induction stoves, because they expect chefs to encounter both. Induction cooktops may present a challenge to cooking ethnic and cultural foods, such as Chinese food made in woks, but the vast majority of cuisines can be comparably made on electric induction stoves. Overall, opposition to gas bans by the culinary community may have less to do with cooking challenges and more to do with the interests of the gas and restaurant industries. The gas industry has found fervent gas supporters among restaurant owners, with San Gabriel’s city council passing Balanced Energy Resolutions, drafted by Southern California Gas Company, to show support for local restaurant owners hoping to keep their gas stoves.

Health Benefits

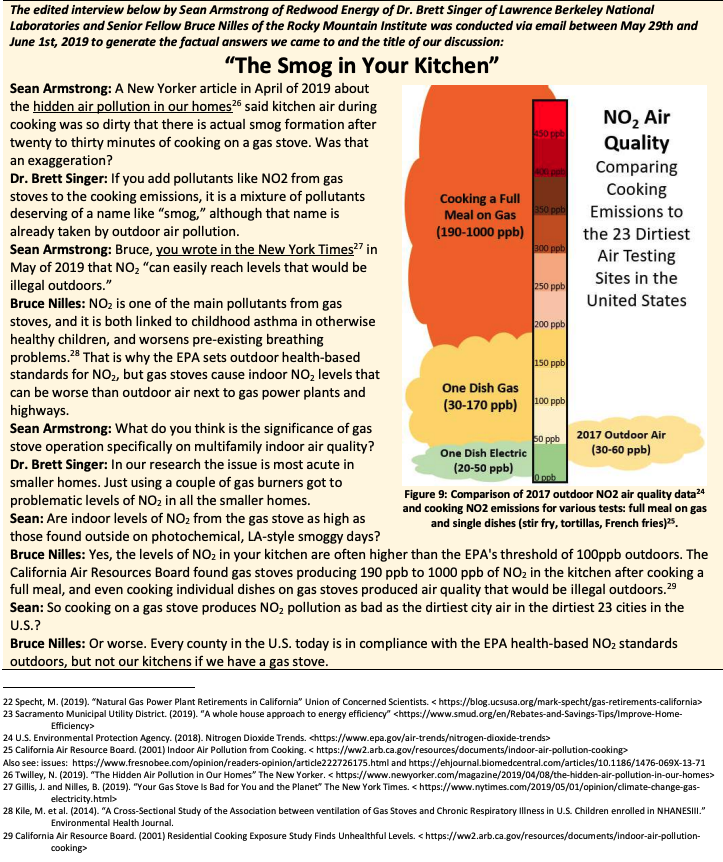

In terms of health, bans on gas hookups prevent exposure to dangerous and dirty pollutants. Sean Armstrong finds, “You have a doubling of asthma in children in the house. It’s a consequence of having just the gas stove, which is a dirty burning, uncontrolled, often un-vented gas burn.” The “supper smog,” created by the mix of gas and toxins emitted by gas stoves, poses a health risk to everyone in the home. The National Institutes of Health published research in 2014 explaining how use of gas stoves contributes to poor indoor air quality, with gas stoves contributing 21% to 30% to the week-averaged indoor air concentration of carbon dioxide. For children with asthma, high concentrations of NO2 in the home is linked to an increase in coughing, wheezing, and limited speech due to respiratory symptoms. Inner-city children are particularly affected due to higher exposure levels from spending more time indoors.

Armstrong continues, “Gas stoves are a danger if they don’t work…we often find literally deadly leaks of carbon monoxide from the ovens, and then frequently dirty burns from the burners, and then gas leaks behind the stove at the connection, all three of which can be so bad that you have to evacuate because it can kill people.” On average, 170 people die per year due to faulty gas-burning appliances.

The health and safety benefits provided a major motivation for the Berkeley gas ban, according to city council member Kate Harrison. “About 27% of our GHGs are coming from the use of natural gas in buildings… there are health implications from natural gas use in the home, particularly for lower income people who may not have good ventilation, etc. … And finally, we live on a seismic hotspot. We have a gas pipeline that runs right under our high school into our homes and we are likely to have an earthquake in the next few years. All these things taken together had led to us to consider banning natural gas in new buildings.” Harrison explains.

Weighing Upfront and Long-Term Costs

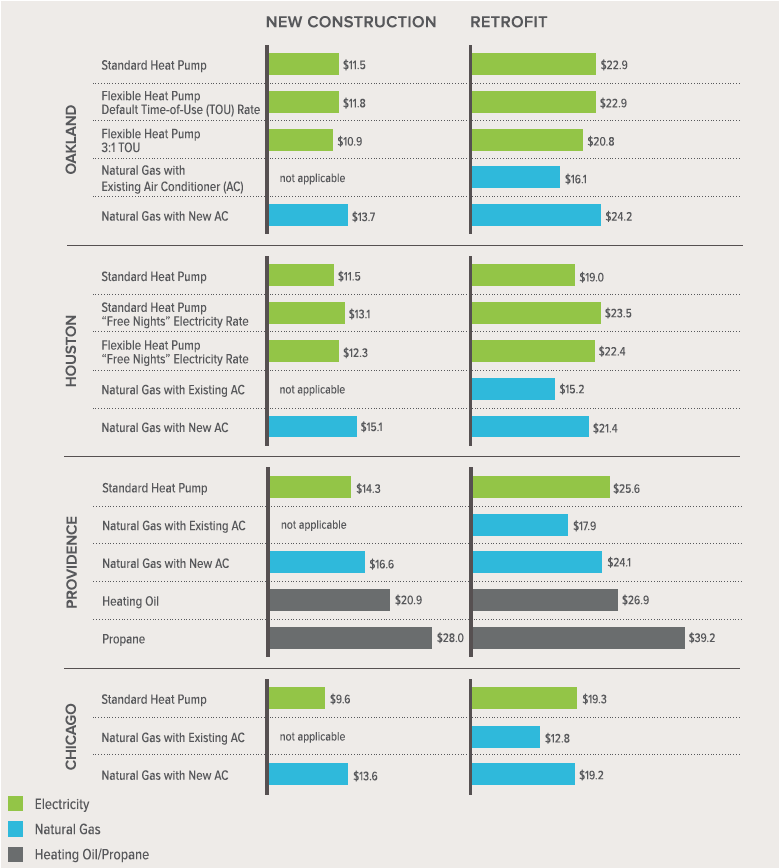

Opponents of electrification point to costs, but recent research from the Rocky Mountain Institute suggests that electrification is frequently the lowest cost option for newly constructed homes. Even retrofitting homes with all-electric home space heating and cooling costs less than a combination AC and gas furnace replacement, when considering upfront and operation costs.

All-electric construction costs less because contractors do not have to connect gas infrastructure, saving time and money. The cost of a gas line extension into new construction costs $5,000 to $10,000 per home, depending on the length of the gas main required. Californians in single family houses save $5,000 over the lifetime of electric equipment and developers save $3,300 per unit in multi-family homes from opting out of gas use and infrastructure.

Electrification also has significant long-term benefits. Rapid electrification of propane and heating oil creates a balance of renewable, highly efficient, and affordable electric power systems. Prices for renewable energy are declining, making electrification cheaper than a reliance on gas infrastructure. The levelized cost of energy for onshore wind and utility-scale solar is already cheaper than gas, even without subsidies. Stopping the expansion of the gas distribution system will prevent gas ratepayers from facing stranded assets in a future of electrified infrastructure. Moving away from gas not only improves long term economic outcomes, as electrification improves health outcomes by removing air pollution from both the home and air in general.

Common Goal, Different Means

Berkeley’s gas ban is one of the most stringent in the nation, with only an exception for gas infrastructure in projects that serve the public interest or buildings that are impossible to build without gas infrastructure. In November of 2019, the California Restaurant Association filed a lawsuit against the City of Berkeley, stating that the gas ban violates state and federal laws regulating energy use standards. The lawsuit also cites negative impacts of the ban that disproportionately affect the culinary community.

Berkeley’s gas ban has created a domino effect, with cities across California passing their own reach codes affecting the use of gas. Mountain View’s reach code has exceptions for gas cooking appliances, but requires contractors to install hookups for electric appliances for future use. Heating, clothes dryers, and water heating are not to use gas. The City of Pacifica’s reach code is similar, but for-profit kitchens and emergency services public agencies are also exempt from restrictions on gas hookups.

Brookline, Massachusetts was the first city outside of California to implement its own gas hookup ban. The fossil fuel industry played a key behind-the-scenes role in fighting the Brookline ban. Opposition by the fossil fuel industry at the local level is part of an effort to prevent a larger movement of municipal gas bans. Industry trade groups also advocated against the ban, citing a loss of jobs and higher energy cost. The Mass Coalition for Sustainable Energy, a front group for gas interests, even sent a letter to local officials advocating against the ban.

The gas hookup ban still passed through the town’s legislative body with a vote of 207 to 3. Brookline’s policy differs from Berkeley’s since it also includes restrictions on new oil and gas infrastructure in future construction projects and substantial renovations, but restaurants, medical labs, and other places are exempt. Brookline’s legislation must pass through the Massachusetts Attorney General’s office before it can go into effect. The Northeast Gas Association is threatening to challenge the new bylaw in court.

Like in California, Brookline’s ban on gas hookups has seeded regional change. However, the Northeast’s cold winters and hot, humid summers makes the transition away from oil and gas harder than in California’s more temperate climate. Despite the opposition by fossil fuel industry interests, other towns in Massachusetts are poised to institute their own reach codes, with Newton in the early phases of crafting legislation and Cambridge holding hearings on its legislative draft.

Back on the West Coast, Seattle’s city council introduced a ban on gas in newly constructed homes and buildings, with an exemption for restaurants. The ban’s goals were to reduce Seattle’s environmental impact, since gas use in buildings accounts for a quarter of the city’s greenhouse gas emissions. However, representatives of businesses and labor unions involved in the gas industry successfully pushed back the vote on the ban, with hopes of commissioning a year long study on the potential effects of the policy.

Taking Away Local Power

In response to cities across the U.S. banning new gas connections, state legislators jumped to prevent cities in Arizona from banning gas infrastructure. The legislation, pushed by legislators receiving contributions from Southwest Gas political action committees, awaits the governor’s signature. Supporters of the statewide measure argue that inconsistency between reach codes proposed by cities would affect ratepayers across the state, increasing gas costs due to decreasing demand. No Arizona cities have plans to ban gas, so this legislation is a preemptive strike on local power. Lawmakers in 5 other states, including Missouri, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Mississippi, also introduced similar anti-ban legislation with near-identical language. With more cities across the U.S. implementing municipal bans on new gas, the gas industry will continue increasing pressure on states to consider similar preemption of local-level energy policy decisions.

Going from Here

Evidence shows that limiting gas connections can benefit public health, reduce energy-related costs, and cut climate pollution. Facing this existential threat, gas industry giants will use their lobbying power to prevent city action. Cities may have to act fast to have an opportunity to act at all.

This article originally posted at ilsr.org. For timely updates, follow John Farrell on Twitter, our energy work on Facebook, or sign up to get the Energy Democracy weekly update.

Featured Photo Credit: Tony Webster via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)