Thanks to Christopher Mitchell, Director of the Telecommunications as Commons Initiative at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance for contributing to this article. You can, and should follow his reporting on public networks at www.muninetworks.org.

Conservatives would have us believe the public sector can’t compete with the private sector. The private sector itself knows better. Nowhere is this more evident than in the telecommunications sector.

Conservatives would have us believe the public sector can’t compete with the private sector. The private sector itself knows better. Nowhere is this more evident than in the telecommunications sector.

People hate their telecommunications companies. The poster child for poor customer service in the public sector may be the Department of Motor Vehicle Bureau, but its unresponsiveness and arrogance pales into insignificance to those of Time Warner Cable, Comcast, and AT&T. In 2010 Comcast, the largest cable company in America bested 31 other companies from all sectors to win Consumerist.com’s Worst Company in America award.

As if to prove it was worthy of the award, Comcast recently pulled $18,000 in funding for a girl’s summer camp because one of the organizers had disapprovingly tweeted about Commissioner Meredith Baker’s jump from the FCC to Comcast just four months after approving Comcast’s $13.75 billion union with NBC. In an e-mail to the group, Steve Kipp, a vice president of communications for Comcast explained, “Given the fact that Comcast has been a major supporter of Reel Grrls for several years now, I am frankly shocked that your organization is slamming us on Twitter. I cannot in good conscience continue to provide you with funding — especially when there are so many other deserving nonprofits in town.” (The resulting uproar from the mainstream media’s reporting led Comcast to rescind the cutoff.)

The increased importance of high speed broadband in everything from business to education to entertainment coupled with soaring prices, slow speeds and bad service from private providers finally led cities to take matters into their own hands and build their own broadband networks.

Today, over 54 cities own citywide fiber networks. Another 79 own citywide cable networks. Over 3 million people have access to these networks. Hundreds more own and/or operate network connecting only schools and municipal buildings. An interactive map showing these networks can be found at Community Broadband Networks.

Cities now view high speed broadband networks as essential infrastructure like water, sewer, and roads. Says Doug Paris, assistant to the city manager in Salisbury, which launched its Fibrant network in 2010, “It’s really not a luxury anymore. It’s a necessity.”

Cities now view high speed broadband networks as essential infrastructure like water, sewer, and roads. Says Doug Paris, assistant to the city manager in Salisbury, which launched its Fibrant network in 2010, “It’s really not a luxury anymore. It’s a necessity.”

For Harold DePriest, head of Chattanooga’s state of the art broadband network and its municipally owned electricity company an even more fundamental issue is involved. Who will write the rules for our information future? “(D)oes our community control our own fate, or does someone else control it?,” he asks.

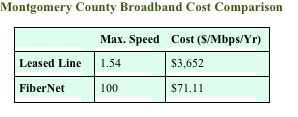

Soaring telecommunication rates are straining already stressed public budgets, leading many cities to build networks for their own use. Montgomery County, Maryland’s network allowed it to stop leasing lines to schools and public buildings, resulting in remarkable savings.

Even the District of Columbia, often trotted out as the epitome of government incompetence, has proven it can outcompete private telecom firms. DC-NET serves over 350 public buildings, including schools, libraries, public hospitals and community centers, saving taxpayers some $5 million per year compared to the costs of leasing circuits. Moreover, with more layers of redundancy than in a typical commercial network, DC-NET has achieved a reliability record far better than the industry standard.

often trotted out as the epitome of government incompetence, has proven it can outcompete private telecom firms. DC-NET serves over 350 public buildings, including schools, libraries, public hospitals and community centers, saving taxpayers some $5 million per year compared to the costs of leasing circuits. Moreover, with more layers of redundancy than in a typical commercial network, DC-NET has achieved a reliability record far better than the industry standard.

For many cities, publicly owned networks are a key element in an economic development strategy. Jory Wolf, Chief Information Officer of Santa Monica’s publicly owned fiber network explains, “When I talk to prospective post-production and tech businesses seeking to relocate to Santa Monica, they tell me it is no longer the cost of real estate, but the cost of IP [transport] driving the decision.” Fiber has helped Bristol, Virginia hold onto existing businesses as well as attract new ones. Chattanooga’s fiber network, which offers 1Gbps speeds, has led to hundreds of new jobs before it was even completed 15 months after startup.

When Real Competition Comes to Town

When a public network opens for business, a town finally experiences effective competition, and it shows.

After Monticello, Minnesota began financing its citywide fiber network, incumbent telco TDS began building its own despite having maintained for years that Monticello did not need more telecom investment. Monticello is now the only city in the country with two competing fiber-to-the-home networks. After Lafayette began building its network, incumbent cable company Cox, which had previously dismissed customer demands for better service as pure conjecture scrambled to upgrade conceding “the people in this area have made it very clear they want faster speeds”.

A Tacoma, Washington, resident who benefits from Click!, its municipal cable network writes, “I have Comcast in Tacoma and all I know is since there is competition down here Comcast is about half the cost as it is in Seattle…A friend in Seattle once called Comcast with both of our bills with similar service and mentioned my price and they said I must live in Tacoma and they wouldn’t match the price. Such is the power of competition.”

A Level Playing Field?

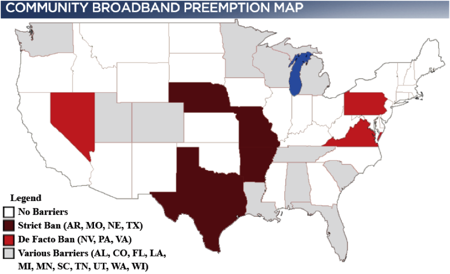

If forced to, private companies will compete, but they much prefer to spend tens of millions of dollars buying the votes of state legislators to enact laws that thwart competition rather than spend hundreds of millions to improve their networks.

Today four states have outright prohibitions on municipal networks. Fifteen others impose significant roadblocks. For example, Alabama requires each communications service (phone, Internet access, and television) offered by a public network to be self-sustaining in isolation from the others. Similarly, in Utah, if the public network wants to offer retail services it must conduct feasibility studies to show the network will cash flow in the first year and that separate services will each cash flow separately. Making a network –a hugely capital intensive investment — cash flow in the first year is all but impossible.

Sometimes the juxtaposition of the public sector’s success in the marketplace and the private sector’s success in rewriting the rules of the marketplace is breathtaking. The small city of Kutztown built one of the first muni fiber-to-the-home networks and Verizon just about broke its neck rushing to the legislature to outlaw the practice before others could duplicate it. Kutztown’s Hometown Utilicom has produced $2 million in savings, a result both of its lower rates and the lower prices charged by the incumbent cable company in response to competitive pressure. This is real money in a small borough.

Sometimes the juxtaposition of the public sector’s success in the marketplace and the private sector’s success in rewriting the rules of the marketplace is breathtaking. The small city of Kutztown built one of the first muni fiber-to-the-home networks and Verizon just about broke its neck rushing to the legislature to outlaw the practice before others could duplicate it. Kutztown’s Hometown Utilicom has produced $2 million in savings, a result both of its lower rates and the lower prices charged by the incumbent cable company in response to competitive pressure. This is real money in a small borough.

In 2004 Governor Rendell gave Kutztown an award for its network. Shortly thereafter he signed Verizon’s bill ensuring no other community would be able to duplicate it.

One would think the private sector, which repeatedly insists the public sector is inept, would have no trouble competing with public networks, especially with all the enormous built-in advantages incumbents have. Incumbent telephone and cable companies long ago amortized the costs of building their network. When a new competitor enters the market, it must build an entirely new network, passing the costs onto subscribers or investors in the form of higher prices or reduced margins. Large incumbents have much more power in negotiating channel contracts because channel owners need massive companies like Comcast to carry their channels. A new network serving a single community might pay 25- 50 percent more for their channels.

Despite the odds, cities have proven quite capable of competing. Rather than recognize that success, the telecom companies have spent years trying to get rid of the competition, most recently in North Carolina.

Time Warner had been trying for years to prevent competition in North Carolina. Its failure to do so has allowed six communities to build public systems, most recently Wilson with its Greenlight network and Salisbury with its Fibrant network. The Institute for Local Self-Reliance compared the rates and speeds offered by Wilson and Salisbury to those offered by large telecom companies like Time Warner Cable and AT&T in North Carolina. The public sector wins hands down.

The success of Salisbury and Wilson led other North Carolina cities like Chapel Hill to seriously investigate public ownership, instilling panic in Time Warner’s corporate boardrooms. Its full court legislative press, coupled with the legislature’s more conservative makeup after November’s elections, finally proved successful. In May, the North Carolina legislature passed a Time Warner Cable-written bill audaciously entitled An Act to Protect Jobs and Investment by Regulating Local Government Competition with Private Business.

The success of Salisbury and Wilson led other North Carolina cities like Chapel Hill to seriously investigate public ownership, instilling panic in Time Warner’s corporate boardrooms. Its full court legislative press, coupled with the legislature’s more conservative makeup after November’s elections, finally proved successful. In May, the North Carolina legislature passed a Time Warner Cable-written bill audaciously entitled An Act to Protect Jobs and Investment by Regulating Local Government Competition with Private Business.

The legislation is popularly known as the Level Playing Field bill, the catchphrase of the cable companies. “The bill is intended to create a level playing field so if local governments want to provide commercial retail services in direct competition with private business, they can’t use their considerable advantages unfairly”, Time Warner announced. “We’re all for competition, as long as people are on a level playing field,” Dan Ballister, director of communications insists.

It’s not surprising that Time Warner would cry foul. That’s what sore losers do when they’re getting whupped. But that legislators echoed this bizarre claim was both surprising and infuriating. For you have to go a far piece to believe that tiny Salisbury, North Carolina has a competitive edge over the mammoth Time Warner.

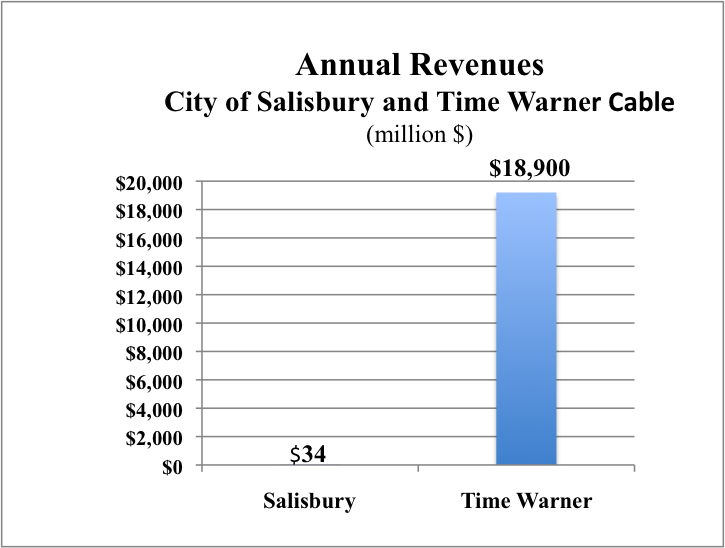

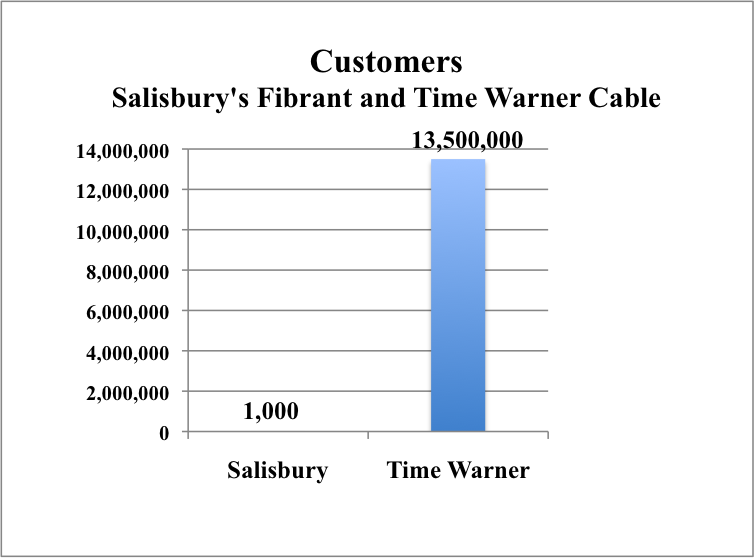

Time Warner’s annual revenues at $18 billion are more than 500 times Salisbury’s $34 million. Time Warner has 14 million customers. Salisbury’s Fibrant network has 1000. We tried to chart the comparative revenues and customers of Time Warner Cable and Salisbury and as you can see Salisbury is so minuscule it doesn’t show up at all!

Let’s be clear. All publicly owned networks would enthusiastically welcome a genuine level playing field in which both the private and the public sector play by the same rules. They know that in a fair fight they win hands down. Heck even in the current situation in which the incumbents have the vast majority of advantages, public networks are winning more often than not.

Let’s be clear. All publicly owned networks would enthusiastically welcome a genuine level playing field in which both the private and the public sector play by the same rules. They know that in a fair fight they win hands down. Heck even in the current situation in which the incumbents have the vast majority of advantages, public networks are winning more often than not.

The private sector’s definition of a level playing field goes only one way.

The recently passed North Carolina law is a case in point. Time Warner Cable can build networks anywhere in the state but the public sector is limited to its political boundaries or very close to them.

A public network must to price its communication services based on the cost of capital available to private providers. This means that if a city can borrow at a lower rate it cannot use this lower cost to offer a lower price.

Which leads to an obvious question. Would the private sector support a similar law prohibiting Wal Mart, for example, from lowering its price to reflect its lower borrowing costs compared to independent small retailers? To ask the question is to answer it.

North Carolina also requires public networks to charge prices taking into account taxes comparable to those paid by private networks. Florida has had such a law for ten years. A 2003 study found that in fact public networks were paying 2-4 times the taxes paid by the private sector.

North Carolina also requires public networks to charge prices taking into account taxes comparable to those paid by private networks. Florida has had such a law for ten years. A 2003 study found that in fact public networks were paying 2-4 times the taxes paid by the private sector.

Terry Huval, Director of Lafayette’s LUS Fiber describes some of the aspects of the currently unlevel playing field.

“While Cox Communications can make rate decisions in a private conference room several states away, Lafayette conducts its business in an open forum, as it should. While Cox can make repeated and periodic requests for documents under the Public Records Law, it is not subject to a corresponding… Louisiana law limits the ability of a governmental enterprise to advertise, but nothing prevents the incumbent providers from spending millions of dollars in advertising campaigns. … To be sure, the ‘playing field is not level,’ but it is the government which is disadvantaged, not the private companies.”

During the early stages of planning and development, public networks often must release their strategies, marketing and product plans to incumbent competitors. Publicly owned networks are unable to surprise their competitors with new products or pricing plans, a significant disadvantage. If incumbents truly desire a level playing field, will they open themselves to the same level of public scrutiny? Of course not.

The North Carolina law, as with many such state laws, prohibit public networks from cross-subsidization, using surpluses from one part of the city to finance the telecommunications system. But the law doesn’t prohibit private networks from doing so. Time Warner Cable can use predatory pricing against competitors because it cross-subsidizes from its vast customer base (largely in uncompetitive areas).

Scottsboro, Alabama overbuilt an incumbent cable company. After Charter bought the incumbent, it cross-subsidized from other markets to finance its predatory pricing against the City. Scottsboro customers were offered a video package with 150 channels for less than $20 per month, even while Charter charged customers in nearby communities over $70 for the same package. Additionally, Charter offered $200 cash for those who made the switch to Charter Cable and another $200 for switching to Charter Internet. In a proceeding at the FCC, experts estimated Charter was losing at least $100-$200 year on these deals and even more when factoring in the cost of six major door-to-door marketing campaigns.

A referendum by the voters is frequently required before a city can issue bonds to finance a public network, a referendum in which the incumbents often outspend those in favor by more than 10 to 1. In Minnesota a supermajority of 65 percent is needed before a public network can offer phone services.

But the North Carolina law specifically exempts cities from any requirement that they obtain voter approval “prior to the sale or discontinuance of the city’s communications network”.

What is to be Done?

What can be done to foster genuine competition in the telecom industry and allow people to decide whether they want to participate directly in establishing the rules governing their digital networks?

1. Speak up. Publicize the successes of the public networks and demand that the choice of whether to build one should be left to the community. Throw the “level playing field argument” back at the Time Warner Cables and Comcasts of the world by fashioning legislation that forces them to play by the same rules as cities. Educate yourself – MuniNetworks.org is a good start.

2. Tell the FCC and Congress to prohibit states from stripping communities of their right to build essential infrastructure. If states rights is justified on the basis of the argument that governments closest to the people should make decisions, the argument is even stronger for local government rights.

3. Demand that federal subsidies allow communities to build their own networks rather than leasing services. For example, federal E-Rate funds aid local schools and libraries in buying broadband. Unfortunately, the rules prohibit communities from using the funds to purchase or build their own network. Federal funds should encourage communities to be locally self-reliant, not increasingly dependent on absentee corporations subsidized by US taxpayers.

This article is also available at onthecommons.org