Citizen Perseverance Pays Off; Still a Way to Go for a Zero Waste City

By Neil Seldman and Kelly Lease

Neil Seldman is Director of the Waste to Wealth Program and Kelly Lease is the program’s Senior Research Associate at ILSR. Seldman is a co-founder of the National Recycling Coalition and the GrassRoots Recycling Network.

Please note: This article was written before the tragic events of September 11, 2001. As such, it makes no reference to the use of Fresh Kills landfill for the debris from the World Trade Center. These events only serve to emphasize the need for the city to develop a sustainable solid waste plan for the future.

Solid Waste Management as if Communities Matter

Cities that listen to their citizens have the most cost effective and environmentally- sound solid waste management systems. By opening up the decision-making process to citizens these cities benefit from creativity, organized and enthusiastic support, and on-going constructive criticism. Unfortunately, rather than find their input welcome, most often citizens have to barge their way into the decision-making process. City administrations in Austin, Portland, Seattle, Los Angeles, and San Francisco had to be dragged kicking and screaming into recycling in the mid-80s. “Without the successful battle that we fought with the City to abandon incineration and adopt recycling and composting,” points out Gail Vittori, a former chair of Austin’s Solid Waste Advisory Commission “the City would be out over $100 million and our environment would be clogged with lead, dioxin, mercury and other life-threatening particulates.”

Look to New Jersey to see that Vittori’s comments apply nation-wide. In the 1980s and early 1990s, New Jersey encouraged counties to develop incinerators. Then, recycling and composting reduced the amount of solid waste, excess landfill capacity was developed in nearby Pennsylvania and Virginia, and a critical Supreme Court decision (Carbone) abrogated the government’s ability to enforce mandatory supply contracts for their incinerators. In response to lower tip fees at landfills, many New Jersey waste haulers opted to bypass local incinerators to dispose of collected trash at the cheaper facilities. As a result of decreasing revenues at the incinerators, in 1998 the state had to bail out five incinerators built over citizen objection. The bailout cost taxpayers statewide nearly $2 billion.

Seattle and Portland started listening to their organized citizens early on. By 1990 both cities abandoned plans for large-scale incinerators, began investing in residential recycling, and supported already vibrant private sector recycling efforts. The cities now have recycling and waste reduction rates of nearly 50%.

Citizens in Los Angeles had a much longer and harder struggle before they were included in the planning and decision-making process. Although five incinerators planned by the City were effectively defeated by 1990, the City persisted in marginalizing recycling for the rest of the decade. Significantly, institutions created in response to the citizens’ anti-incineration battle persevered. The City’s Office of Integrated Solid Waste Management developed both staff and strategies for working with citizens and private companies on recycling, composting, waste prevention, and construction and demolition re-use. By 1999 the Office was fully integrated into the Bureau of Sanitation. “I am a recycling convert”, declared Drew Somes, chief engineer of the Bureau after witnessing the rapid expansion of recycling in the last three years. The numbers speak for themselves. Last year LA recycled 46% of its residential waste. According to Los Angeles Mayor Riordan, the City plans call for achieving a 70% recycling rate. Lupe Vela, a planner from the old Office of Integrated Solid Waste Management, is leading the City’s waste reduction efforts. Vela’s current plans include emphasizing waste prevention and Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programs.

EPR programs require manufacturers to take back or otherwise arrange for recycling or reuse of their products and packages. EPR is becoming increasingly popular around the world. In the U.S., city agencies and grassroots organizations are working together to implement an array of EPR initiatives. These include networking with industry on volunteer programs including economic incentives for new manufacturing techniques, local resolutions calling for EPR measures, bans on certain products, deposits on packaging, taxes on disposables, purchasing and restrictive contracts. The five major cities on the West Coast (San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland and Seattle) are developing uniform EPR measures. “When industry sees that the major Pacific Rim cities are acting in concert” notes Lupe Vela, “I think we will see some dramatic changes in the way they do business.(1)

New York City: A Late Bloomer

New York City is following the path laid out in other cities. In the 1970s, vehement resistance to recycling and waste reduction was the response of city officials who, in the 1980s and even now, prefer 2000 ton per day incinerators over integrated waste management to meet the cities waste management needs. Through the use of timely lawsuits to prevent the construction of incinerators until a realistic recycling program was in place, persistent political pressure at the state and local levels, persuasive analysis, and creative practical solutions, NYC’s organized community and environmental groups have pointed the City in new directions. These groups have stopped the last four administrations’ efforts to build an incinerator in each Borough and have often embarrassed the City’s high priced consultants.

Among the victories of NYC’s community and environmental groups are the City’s forced decisions to regulate private transfer stations, shut all existing incinerators, halt all plans for new “waste-to-energy” plants, plan and implement a recycling program, and close Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island by the end of next year.(2) Citizen groups have also redirected the thinking of the City on its export plan – required as the Fresh Kills landfill will be closed. At the same time community groups and local businesses have contributed greatly to resolving the City’solid waste management problems by introducing the concept of “Borough Self-Sufficiency” (or darn close to it) as an environmentally just way to share the pain of locating facilities near residential areas.

Borough Self-Sufficiency requires scuttling the City’s initial waste export plan, which called for the building of six, 6,000 ton per day enclosed barge unloading facilities (EBUFs). Development of the EBUFs would have required double handling of all waste and devastated low-income communities already burdened with industrial and waste facility pollution. Citizens groups pointed out the inefficiency of this approach and proposed an alternative – containerizing solid waste on the sites of the City’s existing Marine Transfer Stations (MTSs). The City has recently adjusted its plans to include this approach.

As recently as December 2000, the City has responded to pressure from grassroots organizations and committed to implement numerous new programs. These programs include creating community-based Waste Prevention and Recycling Coordinators, hiring staff to concentrate on environmental purchasing, establishing an environmentally-preferable procurement training program for City staff, investing in marketing and recycling-based economic development, and performing a comprehensive study of commercial waste handling within the City.

Still A Long Way To Go

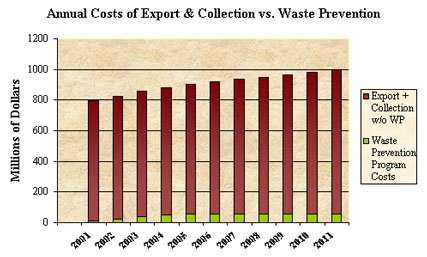

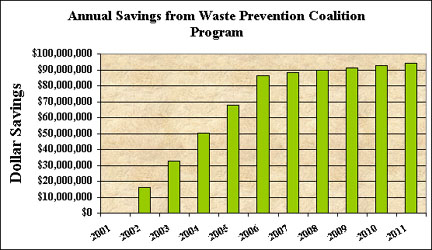

NYC is far from being a recycler’s paradise. The City’s planners rarely involve citizens. Rather, they often release consultants’ reports and have hearings in which citizens point out internal inconsistencies in plans, lost opportunities, and poor priorities. For example, in 1992 the City adopted but never fully implemented a waste prevention plan that was projected to achieve a 9% reduction of solid waste by 2000. Such a reduction would save the City hundreds of millions of dollars in avoided collection and disposal costs. According to Dr. M. Clarke, of the NYC Waste Prevention Coalition, waste prevention is the least cost waste management option for the City.(3)

NOTES: These charts presume:

- Collection costs of $165 a ton, export costs of $115 a ton for a total disposal cost of $280 a ton with no additional administrative cost or cost savings.

- Export and collection costs rise by only 1% per year.

- Second-year waste prevention cost savings are 2% per year, rising to 10% at the end of the 6th year.

The City’s recycling program is a step-child to the disposal system. Officially, the City claims a 14% recycling rate of residential waste. (The City maintains no data on private sector recycling, even though it is responsible for overseeing the system and mandates commercial recycling by law. Observers estimate NYC’s total private sector waste could be twice the 13,000 tons per day generated by the residential sector.) But the City’s recycling data is significantly flawed. The City’s haulers deliver recyclables to processing plants where materials are sorted, baled and shipped to markets. The facilities report the recyclables that the City delivers are so contaminated they cannot recycle from 20-60% of the materials. VISY Industries, Inc., operator of a paper mill on Staten Island, buys paper from the City. The company had to expend an additional $5 million in processing equipment because the paper from the City recycling programs is so contaminated. Thus the City’s true recycling rate is probably closer to 7% than it is to the reported rate of 14%.

The City does not even pay attention to costs. In 1996, Mayor Giuliani called recycling “a fad” and the City’s recycling law “absurd” and cut nearly $30 million from the City’s recycling budget (the funds were later restored). The decision was made without the support of a comprehensive examination of program costs. In 1997, the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG) completed such an analysis which revealed that incremental DOS costs for recycling dropped dramatically from $111,231,000 in fiscal year 1994 to $23,559,943 in fiscal year 1996. Furthermore, the study projected that the cost would continue to fall and predicted that “[a]ny proposals to further reduce service or otherwise undermine the curbside and containerized recycling program may in fact cost the City money rather than save money.”(4)

The trend predicted by the NYPIRG report, that costs of recycling would continue to decline, has been borne out even at very low levels of recycling. “Today, even New York City officials concede the costs of recycling will be less than the cost of exporting waste,” stated Eric Goldstein, a solid waste management analyst for the Natural Resources Defense Council.(5)

The City’s trash disposal costs are mounting. The City expects disposal costs to soar over the next few decades due to the need to shut down the nearby City-owned landfill at Fresh Kills, Staten Island. Once Fresh Kills is closed, the City will need to export all of its waste to out-of-City landfills. If the City were to reach a recycling level of 35%, the savings would be dramatic.

NYC’s Solid Waste Future

Few give NYC credit for being the last great City in the nation to handle all of its waste within its own borders. But with the imminent closure of Fresh Kills, the City will become an exporter of at least 26,000 tons per day of solid waste. Still, the future holds out the possibility that NYC could be the first great city in the nation to recover and use most of its discarded materials within its borders. Throughout the U.S., cities have learned to tie recycling with economic development by attracting or helping to start new businesses that process and use discarded materials for final manufacturing. These new industries bring good jobs and stronger economies in their wake, as they lower the cost of solid waste management. Recycling and reuse firms create from 10-50 times more jobs on a per ton materials basis than disposal.

In NYC, VISY Industries, Inc. is a working practical model. The company built a state-of-the-art paper mill on Staten Island that uses 100% recovered paper as feedstock for its products. The company buys 125,000 tons of paper from the City annually. It receives most of this material from City barges based in Manhattan’s West Side MTS. The company would like to buy twice as much paper from the City. It also wants to build a second plant with another 300,000 ton per day capacity to consume recovered paper. The City’s refusal to provide more materials to the plant is inexplicable. The City sells some of its collected paper on the open market and often gets less than VISY is willing to pay.

Other private firms are doing their part to chip away at the City’s daily solid waste generation. The Hi-Rise Recycling Company builds recycling chutes for apartment buildings to facilitate collection and processing. Building operators who invest in this technology often recover their investment within a few short years through reduced trash disposal costs. The City Green Company is contracting with NYC hotels and event venues to recover organic waste for composting. Again the cost of recycling is lower than the cost of disposal for these generators. The Great Harbor Design Center is establishing a manufacturing plant in the Brooklyn Navy Yard to make S102crete, a newly invented solid-surface construction material made from 83% recycled glass and concrete. It will use 2,300 tons of glass annually and sustain 63 jobs. Deconstruction – the careful takedown of buildings to preserve valuable building materials – and aggregate recycling can reduce 2 million tons of construction and demolition waste in the City while providing the opportunity to train low-income residents for family wage jobs in the construction trades; an industry desperate for trained workers. A full 50% of this C&D waste is from municipally-owned buildings.

The reawakening of the recovery and reuse of waste materials within the City, a hallmark of NYC’s competence at the turn of the last century, is upon the City. As the City implements its new recycling and economic development programs, planners should look at other successful models. New York State provides a model for economic development planning based on utilizing recyclable materials. Its Recycling and Economic Development Program, now merged into the State’s Economic Development Office, is a national leader in providing technical assistance to new companies and to financing their projects. Another economic development tool, a “Productivity Bank,” provides loan capital to agencies to finance waste reduction, reuse and recycling. The loan – plus interest – is paid back through future savings resulting from the investment. Private sector investment in recycling-based enterprises could come from a self-imposed tax on each ton the City exports. A tax of one dollar per ton would create an investment pool of $65 million annually. These public dollars could leverage private sector investment. The tax could be sunset after five years; having helped capitalize NYC’s transition from solid waste as a debt sector to one that is a productive sector of the economy.

Marine Transfer Stations (MTS)

The potential for handling the wastes that do remain in the City in an environmentally and economically sound manner is also bright thanks to the existence of eight Marine Transfer Stations (MTS) throughout the City. By using these facilities properly, the City can share the burden of waste handling fairly among the City’s Boroughs. Technology exists to containerize waste and transfer containers onto rail cars that are then moved out of the City on barges. The barges can move the railcars of containerized waste to barge-to-rail transfer facilities. Once the cars are put on rails they can transport waste to distant landfills without burdening communities in NJ with facilities dedicated to NYC’s waste, such as the 10,000 ton per day facility NYC would like to have built in New Jersey.

One scenario for the use of the MTSs is presented below. The decreasing amount of waste moved in the system reflects progressive increases in the levels of recycling and source reduction. Key elements of this scenario include:

- Construction of trash compaction and containerization facilities on most of the sites of existing MTS facilities;

- East 91st MTS closed to trash, existing MTS used to transport all Manhattan recyclables; South Bronx MTS totally rebuilt for trash containerization and transport of recyclables by barge;

- Existing MTS facilities at West 59th and West 135th not needed because recyclables transported through East 91st MTS;

- Hamilton Avenue MTS site does not have sufficient space for trash compaction and containerization facility and use of existing facility for recyclables, therefore site used for trash only; and

- All other existing MTS facilities used for transport of bulk recyclables directly to markets or processing facilities, new facilities for containerization of trash built on existing sites or adjacent land.

Table 1: New York City MTS/Compaction-Containerization System Scenario for Solid Waste

| MTS | Actual daily tonnage, 1996 | Permitted capacity (tpd) | Design Capacity (tpd) | Daily tons(1) | Compaction / container system | Transport | Cost(2) | ||

| Jan. 2002 (3) | Jan. 2007 | Dec. 2012 | |||||||

| East 91st Street, Manhattan | 605 | 4,800 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Greenpoint, Brooklyn | 2,061 | 4,800 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 1,700 | 1,000 | Trash tipped onto tipping floor then compacted directly in covered and watertight containers using an Amfab-type system at all sites. Containers craned directly onto railcars or barges as appropriate. | Barge containers to an intermodal barge facility.(4) | $40 M |

| Hamilton Avenue, Brooklyn | 1,878 | 4,800 | 2,000 | 1,600 | 1,200 | 900 | $40 M | ||

| North Shore, Queens | 2,182 | 4,800 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 1,850 | $40 M | ||

| South Bronx | 1,917 | 4,800 | 2,000 | 1,500 | 1,300 | 1,000 | $57.5 M(5) | ||

| Southwest Brooklyn | 951 | 4,800 | 1,200 | 700 | 600 | 500 | Railcars moved on float bridge barges directly to rail connection at the Greenville Float Yard in Jersey City, NJ. | $35 M6 | |

| West 59th Street, Manhattan | 767 | 4,800 | 1,200 | 950 | 750 | 550 | $35 M5 | ||

| West 135th Street, Manhattan | 1,237 | 4,800 | 1,200 | 1200 | 1,150 | 900 | Barge containers to an intermodal barge facility. | $30 M | |

Notes: NA = not applicable. Tonnages based on 25% recycling in 2002, 5% source reduction and 31.6% recycling and 2% composting in 2007 (for a net reduction of 35% of 2002 waste generation), and 10% source reduction and 44.4% recycling and 2% composting in 2012 (for a net disposal total of 50% of 2002 waste generation).

(1) Tons for 2002 reflect tonnage flow for that year. Subsequent years’ tonnages reflect anticipated reductions in trash due to source reduction and recycling. Excess capacity could be used by selected private waste haulers.

(2) Cost elements include site preparation, piling, access roadways, parking areas, office and maintenance areas, tipping building compactor systems (conveyors and compactors), cranes, craneways, facility mobile equipment, and engineering and permitting. Costs for land, demolition of existing structures, potential relocation costs for facilities which may be currently occupying the sites, barges and intermodal containers are not included. Based on a minimum 60 barges and 2,400 containers for the system, this mobile equipment cost is an estimated $150 M.

(3) Facilities with 2,000 tons per day design capacity will consist of four (4) Amfab-type compaction systems, while a 1,200 ton per day facility consists of three (3) compaction systems. Typical operation will use only three (3) and two (2) lines, respectively, with the other system serving as a backup.

(4) Containers must be transported to an intermodal container facility for transfer onto railcars or trucks. The City should consider the Port Authority facility at Howland Hook, Staten Island. Such a facility would need approximately 10 acres of land at the site and cost approximately $15-20 M for cranes and railroad line construction. (The Port Authority is currently planning a $20 M expansion of this site. The plan includes improvements to the facility to create capacity to handle containers arriving on barges for transfer to rail.) If the containers were barged out-of-state, permitting issues would arise with the receiving states.

(5) Costs for this facility include approximately $40 M for a new trash compaction and containerization facility, $5 M for the demolition of the existing MTS facility, and $12.5 M for the construction of a new barge slip for transport of recyclables.

(6) Costs for the 1,200 tpd facilities at the Southwest Brooklyn and West 59th Street, Manhattan MTSs would be approximately $5 M higher than the other 1,200 tpd compaction and containerization facility at West 135th Street, Manhattan due to the additional cost of construction of facilities for the handling, loading, and transportation of railcars.

The scenario can easily be adjusted to account for future developments. For example the Port Ivory Recycling and Transfer Company has proposed building, at its own expense, a facility on Staten Island that will include solid waste containerization and recycling and manufacturing facilities. Should this promising plan be brought to fruition, the amount of materials handled at the City MTS facilities would be reduced.(6)

City control of the MTS system is of critical importance to the public interest of the City. In the last few years the Guiliani Administration took major steps toward eliminating the presence of organized crime in the waste hauling industry. The Trade Waste Commission successfully prosecuted six major firms. Prices have already gone down for commercial customers. As of early 2000, commercial trash rates were on average 50% lower than they were a few years ago. However, the City would turn over control of the MTSs to the two large firms that dominate the U.S. solid waste sector, BFI and WMI.(7) These companies would certainly win in any bidding process for control of the MTSs and the EBUFs that the City would build. Some analysts see the City’s plan to build a system of EBUFs as a prelude to combining the residential waste stream, served by the City, and the commercial waste stream, served by small haulers. This idea has even been endorsed by national environmental groups based in NYC. BFI and WMI would readily emerge to dominate this approach.

The City is playing with fire. The City’s independent Budget Office concludes that there may be only two companies to compete for the proposed 20-year contracts for waste export marine transfer station management: BFI and WMI. BFI and WMI have long records of criminal activity. In 1992, BFI admitted to the following: 270 civil penalties, administrative orders, permit or license suspensions and revocations, as well as bond forfeiture actions, 10 misdemeanor or felony convictions and pleas; 24 court decrees or settlement orders during the period from 1981-1991. WMI is a predatory company. WMI CEO, John Drury, told the Wall Street Journal in 1998 that the company benefits from its regional monopolies, i.e., NO! competition . This allows the company to increase prices without losing customers. In 1999, WMI increased prices at its Pennsylvania landfills by an average of more than 40% and nearly doubled prices at some Virginia landfills. The company can do this because they control the market and haulers have no where else to go.

Next Steps for the City and Its Citizens The effort to bring the City to its senses by looking at the favorable bottom line for waste prevention, recycling and recycling based economic development programs has been a long one. The waste reduction and recycling proponents in one way are in a very strong position: they will not go away, while mayors and bureaucrats will. Citizen groups continue to produce excellent research and analysis with clearly laid out practical programs for waste prevention and recycling and economic development.(8)

The next logical step is for the City to embrace, not combat, these efforts. The Mayor should immediately appoint a citizens’ advisory panel to work with the Department of Sanitation as it develops its plans. This would replace the current approach in which citizens are seen as obstacles. NYC needs a decision-making system in which the City and its organized citizens come together to solve what is perhaps the most pressing problem the City will face in the next few years. The City needs a solid waste management system based on community, where the environment and economics equally matter.

(2) For a review of grassroots accomplishments, See Eddie Bautista, Garbage Wars: The Struggle for Waterfront Justice, New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, 1998.

(3) See Marjorie Clark, Testimony on NYC Solid Waste Management Plan Modification 2000, NYC Waste Prevention Coalition, May 2000.

(4) See Arthur Kell, Cheaper Than You Think: Recycling Costs in New York City, NY Public Interest Research Group, December 1997.

(5) Conversation with Eric Goldstein, November 2000. Also, See Eric Goldstein’s testimony before City Council, 22 May 2000.

(6) See Thomas Outerbridge, “The Crisis of Closing Fresh Kills” Biocycle, Volume 41, number 4, April 2000. pp 47-50.

(7) See Ann Gynn, “Study: NYC Plan May Squelch Competition.” Waste News, 4 September 2000.

(8) See Alicia Culver and Resa Dimino, NYC Waste Prevention and Environmental Procurement Program: An Analysis of Progress, Inform, NYC, April 1999; and Barbara Warren, Taking Out the Trash: New Directions for Solid Waste Management in New York City’s Waste, Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods, May 2000; also see Eddie Bautista, Citizens’ Response to the Guiliani Administration’s Solid Waste Management Plan, Lawyers for Public Interest, New York,14 November 2000. For on-going information from NYC’s community based organizations, See Transportation Justice, e-mail newsletter: transportation@nyceia.org.