There are a lot of stories on residential rooftop solar but few if any on what cities are doing to make themselves energy self-reliant by using their own buildings and lands to generate power.

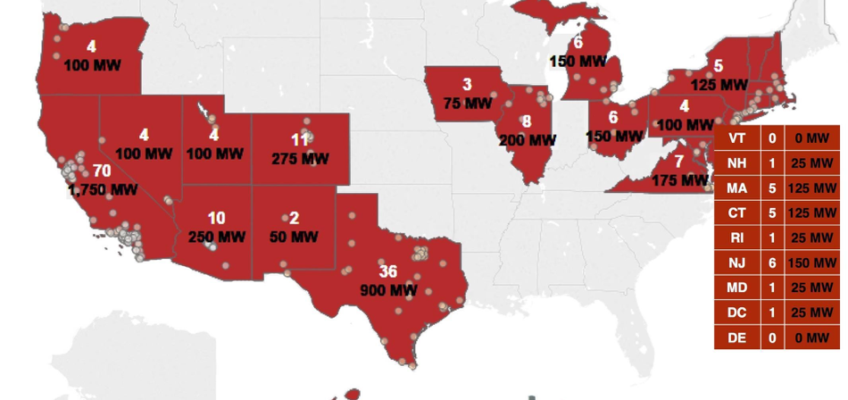

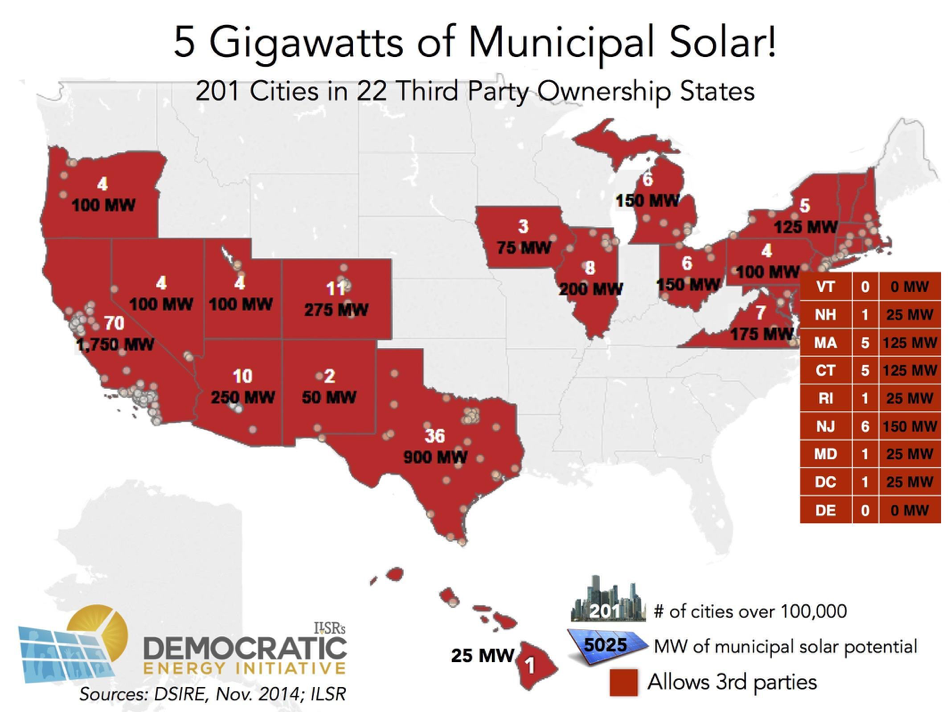

In Public Rooftop Revolution, ILSR estimates that mid-sized cities could install as much as 5,000 megawatts of solar—as much as one-quarter of all solar installed in the U.S. to date—on municipal property, with little to no upfront cash. It would allow cities to redirect millions in saved energy costs to other public purposes.

This report is being released in serial format, beginning Monday, June 1 through Thursday, June 4. CHECK BACK TOMORROW FOR UPDATES.

Read the Executive Summary

Read Part 1 of the report

Read Part 2 of the report

Listen to our podcast conversations with a few of our Featured Five municipal solar cities:

Lancaster, CA city manager Jason Caudle, listen to the podcast, read the interview summary.

Raleigh, NC renewable energy coordinator Robert Hinson, listen to the podcast, read the interview summary.

Kansas City, MO project manager Charles Harris, listen to the podcast, read the interview summary.

Public Solar Economics

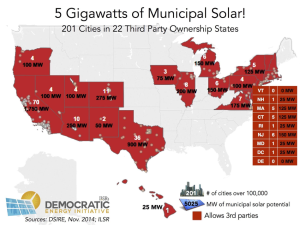

Although the cost of installing solar has been falling rapidly (by nearly 75% over the past 5 years), cities have a substantial disadvantage to private property owners when installing solar. The primary incentive for solar is the 30% federal tax credit, a deal that doesn’t apply to local governments. The federal government also provides accelerated depreciation for solar projects, resulting in a tax write-off worth nearly another 30% of a project’s value.

To access incentives and avoid upfront costs, cities have sought legal arrangements to lease or purchase solar energy via third parties. After all, even half an incentive (typically what’s left for the city after one of these arrangements) is better than no discount, and many cities are reluctant to use their borrowing power for solar in competition with other potential capital expenses.

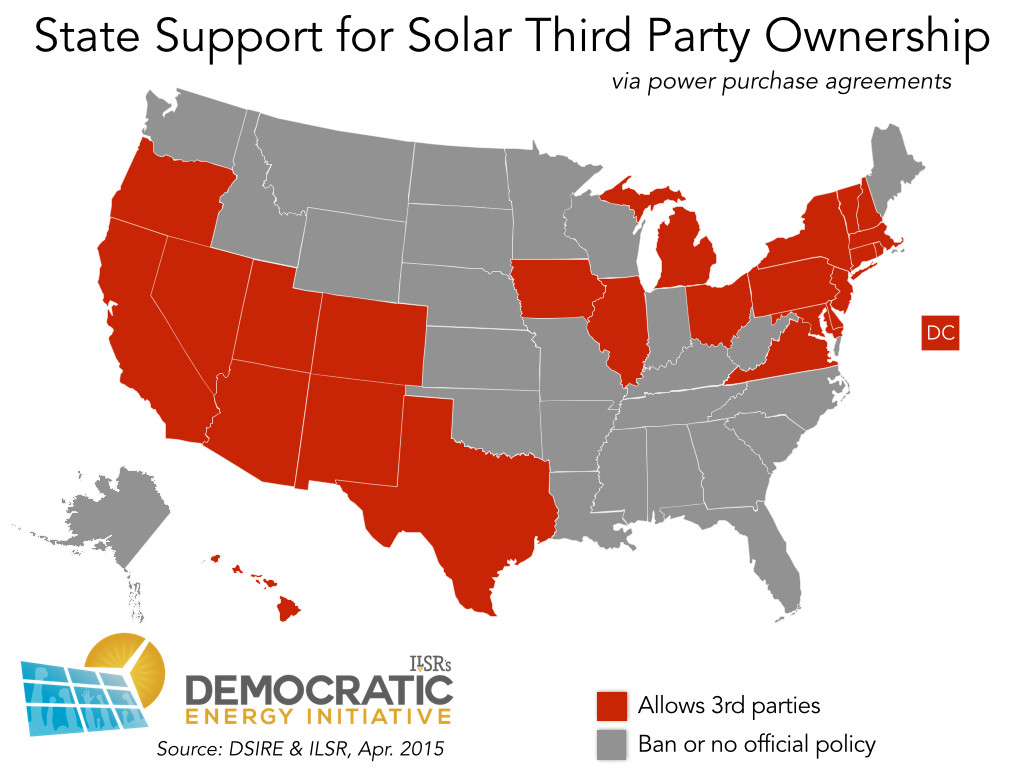

The chart below from ILSR illustrates the challenges for tax-exempt entities like cities in financing solar. A city’s best option is to purchase electricity from a third party (a power purchase agreement, or PPA), but that’s only legal in about half of U.S. states. A lease is second best, but usually allows only capture of the tax credit or depreciation. Direct purchase by the city means no federal incentives can be used. thus more costly energy. Private entities that can use federal tax incentives get the lowest solar prices of all. Using cash grants instead of tax credits—as was done during the aftermath of the financial crisis—would put cities on par with private entities in access to incentives.

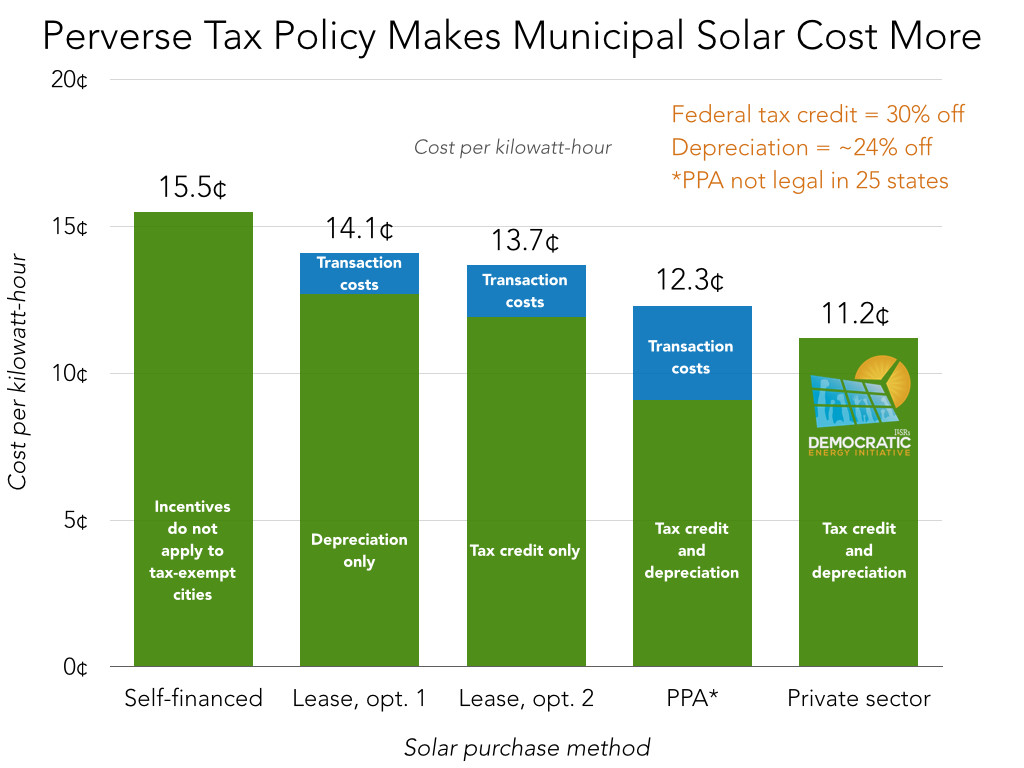

The following chart illustrates the lifetime benefit (also known as net present value) for three primary ways a city can finance a solar array: municipal bonds, a power purchase agreement (with a fixed rate), or a lease. We use the same cost assumptions for all three scenarios, although they differ most in that a city-financed solar array gets no incentives, a leased project (in our example) can use the federal tax credit but not depreciation benefits, and a power purchase can use both tax credits and depreciation. The selected cities are highlighted later in our Featured Five section.

Third party ownership fares better than direct city investment in every case, largely because the solar developer can use and pass through one or both federal tax benefits. The relative benefit of third party options is substantial, especially for cities with low electricity prices and relatively weak sunshine, like Raleigh. In cities with high electricity prices, like New Bedford, or abundant sunshine, like Lancaster, direct city ownership is economically viable, if less attractive.

The following table shows the information presented in the above chart.

To understand a bit more about how third party ownership can help cities save money immediately, the following table shows how a power purchase contract or a solar lease would impact a city’s budget on day one, if a city were able to sign this kind of third party agreement.

It should be noted that Raleigh’s case is hypothetical because the power purchase contract is not legal in North Carolina (hence the strikethrough), but it’s also instructive. Despite having a higher price than the current cost of power from the electric company, the power purchase agreement or the lease is worthwhile in the long run. This is because the city can buy the system at a fraction of its upfront cost when the agreement expires, and continue to get electricity with no additional payments

In reality, Raleigh may have already discovered a better option. Instead of leasing the panels of the solar project, the city is leasing land to solar producers, with an option to purchase the solar array after 7 years (when the initial owner has cashed in the federal tax incentives).

The above comparisons are meant to be illustrative, since many cities—like Raleigh—don’t have recourse to power purchase arrangements. As of April 2015, in fact, laws governing this form of third party ownership were either unclear (making projects risky) or clearly disallow it in 26 states.

The Policy Difference

Third party ownership laws are a state fix for a federal incentive problem (although it can simplify solar for public or private building owners). If the 30% discount were available to local governments without complicated legal arrangements, then solar barriers would drop substantially. For example, if New Bedford could use the 30% federal tax credit, city ownership would stack up very favorably to third party ownership, especially given the city’s edge in obtaining low-cost financing.

Sensitivity

While our assumptions about power purchase and lease terms offer a particular picture, they are just assumptions. What if electricity prices stop increasing or rises faster? What if a city signs a power purchase or lease contract that escalates in price each year?

The following table illustrates how changes in our assumptions changes the lifetime value of solar to a particular city: New Bedford, MA. Figures in bold are values that change based on our sensitivity assumptions.

There are a few lessons in this analysis:

Since electricity prices are expected to rise, a fixed power purchase contract can have a significantly higher price (A) than a city’s current electricity price and still be a good deal in the long run.

With a lease contract (or PPA), if the annual cost inflates too much (B), the value of third party ownership compared to city ownership largely disappears.

Assumptions about electricity cost inflation matter a great deal. If we assume prices rise by only 1% per year instead of 2.5% (C), it sharply reduces the value of solar, although it’s still greater than zero. Much higher annual increases in grid electricity prices (D) makes all ownership options very attractive.

Even with fairly conservative assumptions about electricity prices and potential contracts, third party ownership makes sense and saves cities money on solar energy.Barriers

Many cities have identified barriers to expanding municipal solar installations, and sometimes ways to overcome them.

Physical Limits

An initial screen of solar suitability focuses on building rooftops, and many public buildings may lack structural strength to host solar, have obstructions on the roof (e.g. from heating or cooling equipment), or have significant shading. Generic studies of rooftop potential show that as much as 40% of commercial building roof area is unsuitable for solar because of shading or structural inadequacy. Cities may also be reluctant to install solar if the building roof is old, since roof replacement requires moving and reinstalling the solar PV system.

Charles Harris, Project Manager for Kansas City, says that over 90% of city properties are unsuitable for solar and cited insufficient structural integrity and unsuitable surroundings as two primary reasons.

Even accounting for these barriers, however, few cities have built anywhere near to their maximum solar potential. In other words, there are additional barriers.

Historic / Aesthetic

In some cities, municipal buildings may have historic significance, and installing solar may be prohibited or restricted by state and federal law. In other cases, solar will––in the mind of local officials and/or residents––detract from the building’s appearance.

There have been several prominent news stories about solar on historic (though not municipal) buildings. Several neighborhoods in New Orleans have historic designation, limiting what homeowners can install and blocking at least one residential project. Historic preservation guidelines in Washington, DC, suggest that panels should not be visible from the street, causing a home rooftop project to be halted. In Texas, some residents who oppose solar installations in their neighborhood because of aesthetic reasons or a fear that a neighbor’s solar system will reduce their property value, are using their homeowner association covenants to try to stall or stop solar installations.

State and national guidelines tend to strike a balance. The state of Massachusetts recommends against cities adopting restrictions on solar related to aesthetics, as it can “create roadblocks to actual installations.” The National Trust for Historic Preservation highlights a number of successful state and local policies for accommodating solar installations on historically designated properties.

Even with historic buildings, national solar installers—Tony Clifford, CEO of Washington, D.C.-based Standard Solar and C. Tucker Crawford, CEO and co-founder of New Orleans-based South Coast Solar LLC—feel solar and historic properties can co-exist:

Crawford and Clifford do not believe that solar guidelines for historic districts are too onerous for installers. A typical New Orleans house, for example, has a required setback distance of about 10 feet from the front of the home’s wall line to where a panel can be installed.

Once again, this barrier likely applies to a minimum of municipal buildings in most cities.

Cost

Money is a frequently mentioned barrier for solar. With a high initial cost, a cash purchase of solar competes against other city general fund priorities. Even if the city borrows the entire cost of solar, its capital budget may be restricted by the city’s existing debt load (and finance payments), state limitations on city borrowing, or by competition from other capital investments (e.g. roads, buildings, etc.).

Cities are also ineligible for the 30% federal tax credit and accelerated depreciation, and alternative incentives (such as clean renewable energy bonds) may require staff time for applications and/or funding approvals from Congress.

Third party ownership––power purchase agreements and leasing––allow cities to skirt both upfront and borrowing costs, and to access financial incentives for solar. But as mentioned previously, cities in 26 states could be prevented from using these ownership structures.

Raleigh, NC, has perhaps the most creative workaround on upfront costs and legal limitations. Their solar installations provide the city revenue simply from leasing the land or rooftop on which the solar installation is located. In time, the city may be able to buy out the developer and directly own the solar array (and use the energy), at a fraction of the initial cost. This may be a strategy that more cities can employ, but likely requires a utility to purchase the electricity.

Expertise and Legal Issues

Some cities have been hesitant to more aggressively pursue solar, even with cost-effective third party opportunities, due to worries about getting a good deal from solar providers. These cities may have minimal experience with negotiating energy purchase, lack legal expertise or have other perceived barriers. Some cities, such as Kansas City, specifically mentioned lack of sufficient dedicated staff time as a barrier or that negotiation process was a hassle.

Other cities, like Lancaster, have responded that the risks of signing solar contracts is little different from other procurement, and just requires due diligence in contract writing. Denver found the negotiations simple enough that it shifted away from direct ownership to power purchase contracts.

Bureaucracy

Although opinions differ between the solar installers we spoke with, some consider working with municipalities to be fairly onerous. One solar developer in the Southeast was particularly grim—”We don’t have the time or money for bureaucratic government.” In particular, he noted the “large transactional cost” but also that tax equity investors (required to absorb the tax incentives that cities can’t use) prefer larger projects to the relatively small scale of work in cities.

A solar developer from Borrego Solar also noted the complexity of municipal decision making in an interview for Solar Industry magazine:

Borrego Solar’s [Joe] Harrison says he encountered many of the unique aspects of dealing with municipalities as customers in developing a 2.7 MW project for the City of Beverly, Mass. The array is on a private site, but the city is purchasing the net metering credits. Harrison says the approval process involved five city council meetings, three subcommittees and two public meetings.

“We had sort of thought we would receive approval at the first meeting,” he says.

But in the same article, Harrison also said that municipal contracts have their upside:

“There are pros and cons to working with municipal customers,” says Joe Harrison, senior project developer in the Boston office of San Diego-based Borrego Solar Systems. “The private sector is able to move quicker when they make a decision. On the other hand, the private sector is not obligated to follow through. You are always one phone call away from having the customer go with someone else.”

[Municipal customers] are big users motivated to do the right thing for the community,” he says.”

The good news is that cities have choices among contractors. Tom Tuffey, vice president of Community Energy Solar LLC in Pennsylvania said that “in some cases, we have had municipals with up to 40 solar developers that have approached them.”

Net Metering

Although it’s a crucial policy enabling solar installations, net metering—allowing electric customers to reduce their energy bill by netting their solar energy production against their energy consumption (on a monthly or annual basis)—can also be a barrier. To use net metering, the solar installation must typically be on the property and connected to the same meter where electricity is being consumed. States may have size limits on net metered solar installations, e.g. 50 kilowatts. In this case, a building that uses more energy will not be able to offset all its consumption, even if it had sufficient sunny roof space.

Certain net metering rules can lift these limits. Some states have no hard size cap at all, but simply restrict project size and output relative to onsite electricity use. Other states have “aggregate net metering,” allowing electric customers to offset energy use at multiple meters/buildings with a single solar array connected to one of them. “Virtual net metering” goes a step further, allowing the solar to be installed offsite.

TOMORROW…

To access incentives and avoid upfront costs, cities have sought legal arrangements to lease or purchase solar energy via third parties. PART 3: THE THIRD PARTY TRUMP CARD & A HOW KANSAS CITY, MO, REBATE PLAN IS THE TICKET FOR SOLAR OPPORTUNITY.

This article originally posted at ilsr.org. For timely updates, follow John Farrell on Twitter or get the Democratic Energy weekly update.

Rooftop Revolution: Past Reports

In 2012, ILSR published a pair of reports that projected, by 2021,10% of electricity in the U.S. could come from solar and at a lower price—without subsidies—than utility-provided electricity. In 2014 and 2015, Environment America’s Shining Cities reports examined how cities were catalysts for solar development.

By 2022, over 38 million homes and businesses could get solar power from their own rooftop, pay less for electricity, without any subsidies for solar. These two reports, published in 2012, outline the growth potential for local solar power and the coming rooftop revolution. Click to see more of our Rooftop Revolution resources.

|

|