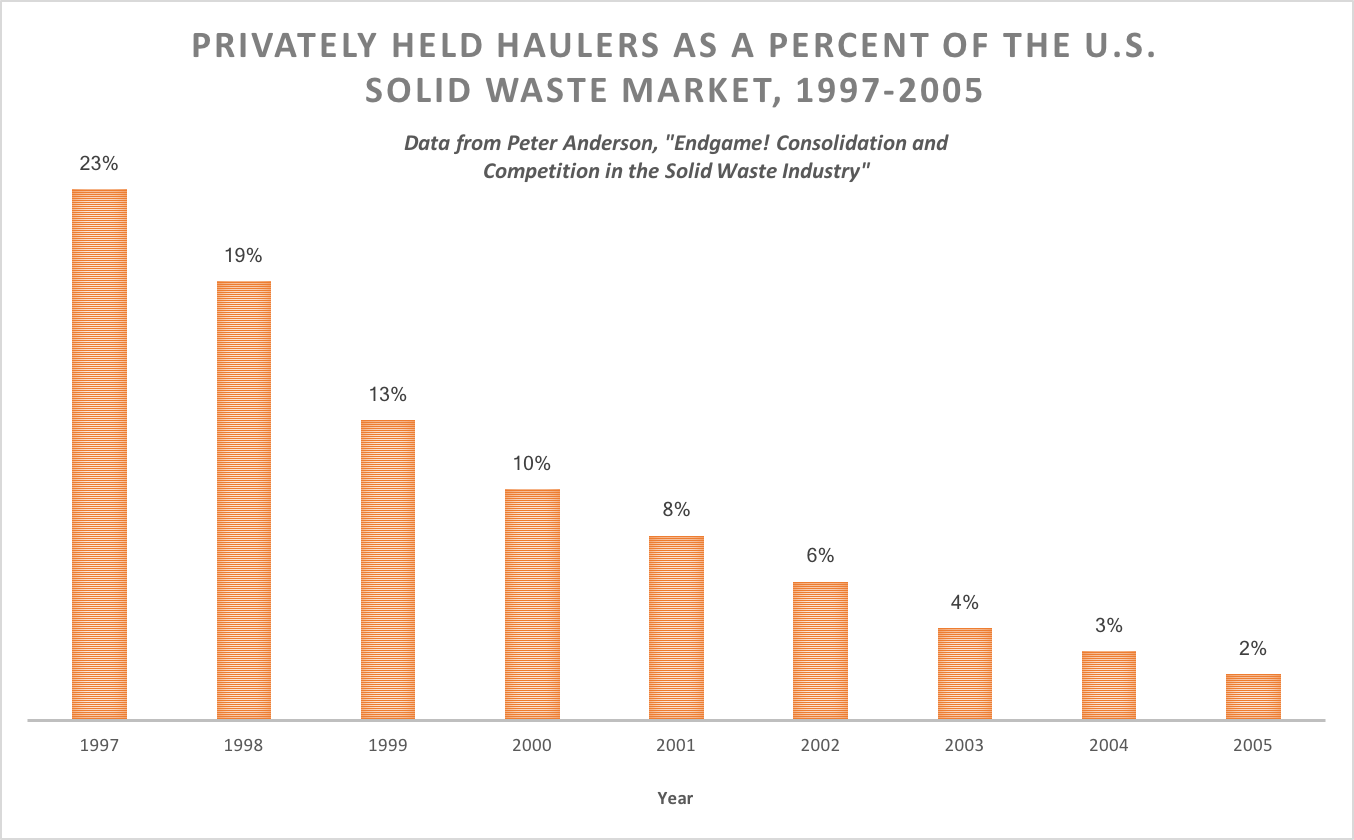

Big Waste dominates every aspect of solid waste and recycling practice and policy. The top four consolidated companies earn $30 billion of the $70 billion economic sector. Big Waste companies own or control 75% of the permitted landfill capacity in major metropolitan areas, and control an estimated 50% of the national hauling market, with increased levels of domination in regional markets.

When the grassroots-recycling phenomenon that swept the nation in the last generation made recycling and economic growth the focus of “materials” management, Big Waste correctly saw this as an existential threat to their market control and political influence. Recycling was the enemy of profits and influence because it diverted materials that should go to landfills.

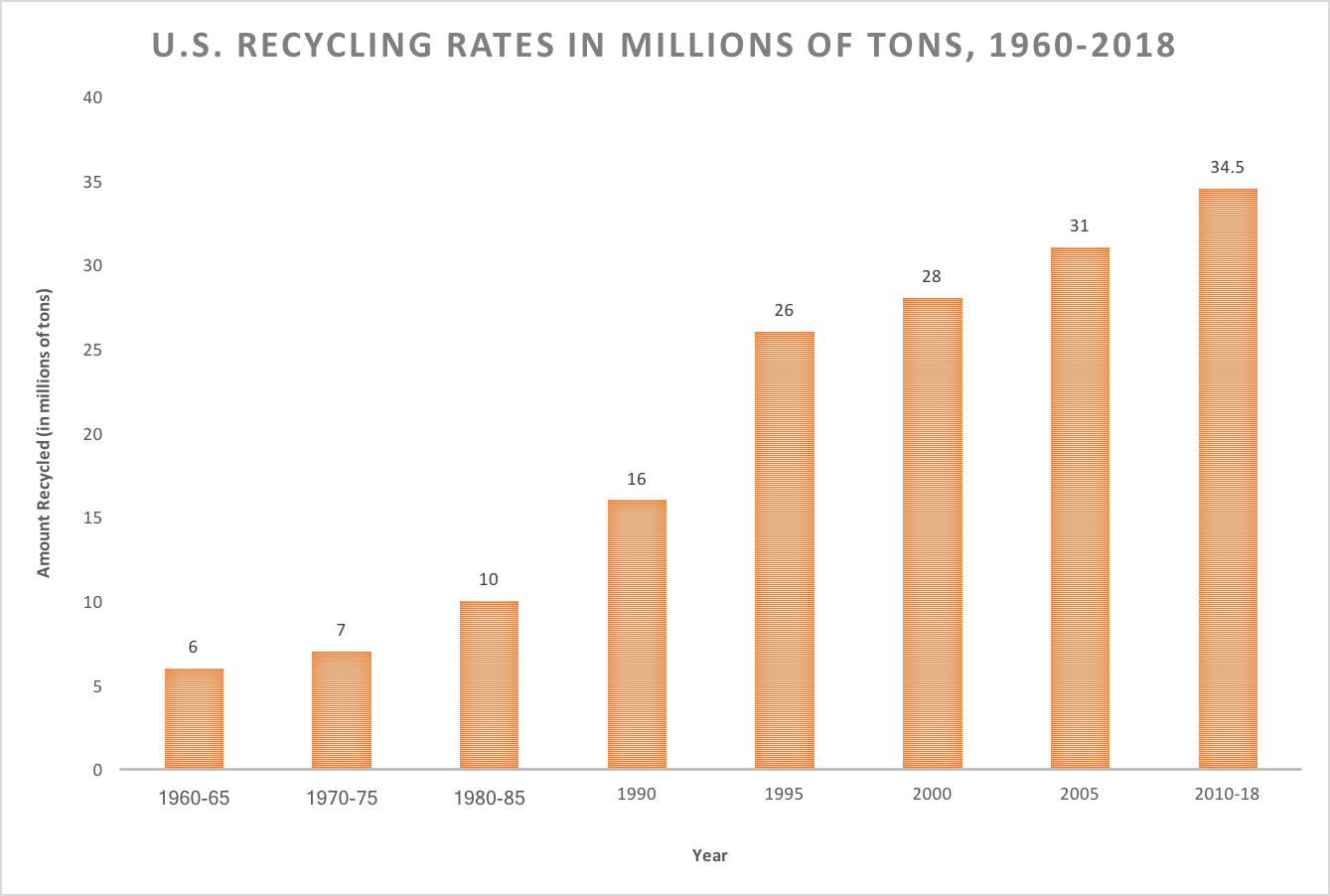

Recycling, seen as an escape valve from the grip of Big Waste, grew rapidly from the 1970s to 1990s. But growth slowed and eventually stagnated by the 2000s. While some cities and towns have reached 50%, 60%, and even 70% recycling rates, most major U.S. cities recycle at 20% or less. The national recycling rate has been 35% for the past half decade and shows no signs of picking up steam again.

Profits from operating landfills under Big Waste control typically are 60%-70%, but recycling yields at best only marginal returns and can lose money as well. Flat recycling values allow for increases in processing fees. Landfill rates can increase as well as long as they do not stimulate more recycling.

Monopoly Defined

Some people assume that a company must be the sole supplier of a particular product or service to be considered a monopoly — after all, “mono” means one.

A corporation that has less than 100 percent of a market, though, can still be powerful enough to cause harm by elbowing out smaller competitors, compelling workers to accept wages lower than they could command in a more competitive market, or driving prices higher than they would otherwise go. It’s this power to manipulate a market for one’s own advantage or profit that’s at the heart of how policymakers and economists define monopoly. A company need not have “a literal monopoly” to qualify as a monopolist. The Federal Trade Commission defines a monopoly as “a firm with significant and durable market power.”

When Standard Oil was broken up in 1911, for example, it controlled 64 percent of the U.S. oil industry. A 1966 Supreme Court decision rejecting the takeover of one supermarket chain by another in Los Angeles because it would create a monopoly by acquiring 7.5 percent of area sales.

— Stacy Mitchell, Co-Director, ILSR, November 2018

The Post World War II Economy

Before World War II, solid waste was not a significant enough problem even for quantification. Low capital requirements for entering the waste sector allowed tens of thousands of independent haulers to thrive. With a salesperson and the purchase of one or two trucks and a fleet maintenance yard, companies could easily grow to 5-10 trucks and a maintenance yard for maximum efficiency. Open bed trucks allowed for sorting recyclable materials and reusable products. Remaining waste was tipped at small private or publicly owned landfills. In these days, landfills were often open dumps: a played out quarry, a lonely canyon, a farm with a bulldozer, or wetlands and the shores of lakes and bays. Pollution flowing from these sites assaulted air, waterways, groundwater, and soils.

New families with good jobs in an expanding economy and veterans’ benefits used the new roads to swarm into the suburbs and fuel the new consumer lifestyle. In 1961, Sam Yorty ran for mayor of Los Angeles with a slogan that typified American attitudes: “We won the war and we don’t have to recycle.” The new mayor cancelled curbside collection of recyclables.

Open bed collection vehicles gave way to new 10-ton capacity trucks fitted with hydraulic compression to push, squeeze, and crush materials into an unrecoverable mass. Materials and products that were formerly recycled and reused became waste. Pig farmers who made collection runs for food waste from urban centers began to disappear. Food waste was added to the unwholesome mixture.

The new suburban jurisdictions became politically powerful and stopped construction of new landfills near urban centers. As landfills moved further away from population centers, transfer stations were needed to move trash from garbage trucks onto tractor-trailers in order to haul waste longer distances. Recycling, the hallmark of wartime efforts by citizens on the home front, disappeared. Only a few “scrappies,” or junkyards, remained.

The solid waste infrastructure was overwhelmed by the 1960s. In the 1970s, the environmental movement arose, and one of its targets was waste pollution. The Clean Air Act shut down “waste destructors,” open-air incinerators that exacerbated air pollution and left heaps of ashes blowing in the wind through cities. The Environmental Protection Agency was formed in 1970. By 1973, the National League of Cities identified solid waste management as their primary concern.

Consolidation

In the 1950s, 12,000 small independent garbage companies collected waste from commercial accounts. Clever businessmen with access to capital saw an opportunity to form vertically integrated national companies. The consolidation made no sense in terms of efficiency. In fact, industry executives saw expansion beyond an urban center as a drag on efficient management. “The reality of this industry,” a Big Waste CEO stated, “is that it’s local. There is no great synergy in running businesses in Chicago and Indiana, let alone in the Northeast from [one central location].” But market share, political influence, and pricing more than made up for administrative inefficiencies.

The transformation of the fragmented system of independent haulers began with rough competition, with price fixing and low-ball (below market) rates driving some haulers out of business. Other tactics included intimidation of rival drivers and clients, and vandalism (with fires and baseball bats), which received wide notoriety. These practices were indulged through cronyism with municipal managers. Businessmen convinced Wall Street of the profitability of a national hauling company with access to capital, as national companies could consolidate the industry and yield higher profits.

By the late 1960s, the use of underworld practices were abandoned in favor of a cleaner corporate image. Waste Management, Inc. and Browning Ferris emerged as the first highly successful, vertically-integrated consolidators in 1968. The process continued into the 1990s, as consolidator companies were themselves consolidated through mergers and acquisitions in a seemingly never-ending cycle of national and regional consolidation.

Big Waste companies bought rival companies with their corporate stock, in a frantic effort ensued to ensure that stock prices remained high. The end game came in the late 1990s, when egregious activity led to class action suits costing some $50 million. It then came to light that between 1976 and 1997, Waste Management, Inc. and Arthur Anderson, Inc. had been cooking the books, changing records to appear to be far more profitable than they actually were. In the largest corporate scandal until Enron, the two companies had to pay over $600 million in fines for their ill deeds. But Big Waste was allowed to keep their empires intact. No “bad boy” laws kept Big Waste from benefitting from public financing. Professional managers replaced acquisition specialists as the image of Big Waste was brushed up. But Big Waste was not forced to disband their empires under antitrust laws.

The consolidation of control over landfills paralleled the concentration of waste hauling. Federal solid waste management regulations — spurred by growing environmental consciousness in the 1960s — gave rise to new landfill regulations in 1976 that took effect in the late 1980s-early 1990s. These regulations favored well-capitalized companies, which could afford the plastic linings and leachate and methane recovery technologies that local governments and small landfill owners could not. (Leachate is the chemical soup that drains or leaches from a landfill.) Instead of a national program to finance public landfills, as was provided for municipal wastewater and sewer infrastructure, the implementation of Subtitle D landfill regulations was left to Big Waste. Democratic control was abandoned to private cartels.

This resulted in the closure of small private and community landfills, from 10,000 in 1980 to 6,000 in 1990 and 2,000 in 2000. In 2018, there were 1,600 landfills operating. Landfill capacity actually increased as Big Waste developed vast landfills capable of receiving 3,000 tons daily. If landfills are not publicly owned, federal law allows private landfills to bring in waste from any jurisdiction, which meant that mega landfills made Virginia, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania the waste destination for East Coast and Mid-West municipal waste.

Big Waste also set its sights on waste incineration as another way to vertically integrate all its operations. The industry created the National Center for Resource Recovery to act as the Keep America Beautiful for waste incineration. EPA and DOE were willing to adopt this antidote for managing the constantly growing waste stream due to growing population and increased consumption of throw away and single use products. EPA gave cities planning grants, waived hazardous waste rules for ash, and supported venues featuring incineration sales forces. DOE provided “commercialization grants” to incinerator companies. Legislation in 1979 guaranteed sales for electricity produced by burning garbage.

To city managers, incinerators were a fine alternative to landfills. There was no need to change any practices and incinerators were often closer than landfills. To incumbent politicians, the hundreds of millions of dollars of bonds issued yielded revenue from arbitrage transactions and provided financial patronage to consultants, lawyers, and political friends.

In the 1980s and 1990s, 350 proposed incinerators, ranging in size from 1,000 to 4,000 tons per day, alarmed the public in every major population center in the country. Cities entered into “put or pay” contracts requiring minimum amounts of waste delivered to facilities, greatly limiting recycling efforts.

But organized citizens and small businesses nationwide said no in a spontaneous and ad hoc anti-incineration movement. In 1985, more incinerator capacity was cancelled than proposed. In all, 300 incinerators were defeated. Only one new incinerator has been built since 1996. Since 2000, another 100 proposed facilities have been defeated. Since 2010, Big Waste companies have closed their waste incineration subsidiary companies, and now focus on processing waste into fuel, or refuse derived fuel, RDF, to burn in existing cement kilns and industrial boilers.

Local decision making and democracy won out as many activists quickly assumed control over decision making on solid waste at the city and county level. Organized citizens, with support from small business owners, brought close scrutiny to the financial and environmental consequences of large-scale waste incineration. Technical reports revealed consequences previously not considered by elected officials. Citizens ran for office and won, utilizing public office to write new rules requiring recycling and composting. In Paterson, N.J., Bill Pascrell, a medical doctor turned anti-incineration organizer, became mayor and then Congressman.

This happened from all over the country, from California to Texas to Florida. The turnaround could be quite dramatic. In Duarte, Calif., the city council approved a 10,000 tons per day incineration facility to burn all of Los Angeles County’s waste. Three hundred citizens of this small city showed up at the next meeting to voice their displeasure, and the vote was immediately reversed. So angry were the citizens that an entire new slate of councilors was elected at the next election. In Lowell, Mass., citizens reversed an 8-1 preliminary vote to allow an incinerator when they announced that they and their children would never again vote for anyone who approved the plant. The new vote was 9-0 to cancel the planned incinerator. In Alachua County, Fla., a housewife, Penny Wheat, testified against a planned incinerator. She was told to go back to her kitchen. She did and organized a campaign for County Executive that won more votes than any other election in that county’s history. The incinerator was cancelled and investment in recycling and composting began. The county will soon meet the state diversion goal of 75%, without incineration. In Austin, Texas, the City Council cancelled an incinerator after construction had started when citizens and businesses pointed out that the city could save over $100 million during the 20-year life of the plant if the city composted, recycled, and used local low cost landfills instead. The city absorbed a $22 million loss, cancelled the incinerator, and invested in recycling and composting.

Grassroots recycling started in the late 1960s. Drop-off recycling centers became the symbol of the movement after the California Survival Walk led by recycling pioneer Cliff Humphrey. After the first Earth Day in 1970, 2,000 to 3,000 drop-off centers were started throughout the U.S., mostly by women activists in their backyards, at abandoned gas stations, or on college campuses. By the end of the 1970s, recycling entrepreneurs would grow these symbols of practical conservation into curbside collection companies. EcoCycle in Boulder and Eureka Recycling in Saint Paul remain operational. Many were sold to local haulers or dismantled (with a sigh of a job well done) as cities started implementing municipal recycling in the late 1970s. Today municipal programs are ubiquitous. Recycling proved to be the most successful environmental program in the U.S., propelled by a mobilized constituency that crossed age, gender, class, race, and political lines. Recycling contributes over 100 million tons of raw materials to industry and agriculture annually.

EPA and the waste industry initially insisted that no more than 10% of municipal solid waste could be recycled. By the 1980s, so many cities had plowed through that “limit” that they raised the maximum that could be practically achieved to 25%. In 1991, ILSR published a report based on case studies of cities that had gone beyond 40% recycling, and followed that up with Cutting the Waste Stream in Half, a 1999 report documenting cities that reached 50% recycling. New rules — minimum content, mandatory recycling and composting, unit pricing for garbage, bottle bills, purchasing preferences, product bans, bans on recyclable and compostable materials from going to landfills and incinerators, resource recovery parks for recycling and composting industries, reuse centers for repair and resale companies, waste surcharges to accumulate investment capital for industry and government infrastructure — were established by local and state governments following the lead of their constituents.

By 2000, the recycling sector comprised 56,000 companies, tens of thousands of government programs, 1.5 million jobs, and annual sales of $300 billion. Recycling captured the hearts and minds of the American people. Yet today the recycling rate has stagnated.

In order to stem the tide of recycling, Big Waste took action to protect its hauling and landfill market shares. It introduced single-stream recycling in which all recyclables were put in a single cart, and started gobbling up materials processing capacity. In 1995 only five cities in the U.S. had adopted single-stream recycling; by 2003, that number had risen to 94. Soon single-stream became the norm with, 65% of the population using single-stream in 2010, up from 29% in 2005. The percentage of the U.S. using dual-stream systems (which keep paper separate from glass, plastic, and metal) plummeted from 70% to 34%.

Cities were convinced that single-stream would increase recycling participation and rates. Instead, recycling rates stagnated, except in motivated cities, and most cities had to transport their materials long distances to centralized MRFs established and owned by Big Waste. Washington, D.C. dropped dual-stream recycling and put an in-town processor with 25 workers out of business. The city now spends an estimated $500,000 to ship recyclables 40 miles to a mega processing facility. The city’s recycling rate remains stagnant.

Boulder, Colo. and Saint Paul, Minn. have demonstrated that single-stream can work with properly-scaled facilities of 200 to 300 tons per day, which are owned and operated by entities that want to recycle. But for over-scaled 900 to 1,000 ton per day facilities, profits come from collection contracts, not from sales of quality recyclable materials. Big Waste gets paid for collection and processing — revenues from sale of recycled materials are irrelevant. Hence mass throughput is required for profitability.

Big Waste consolidated ownership of material recovery facilities (MRFs). Consolidated companies now own 50% of the estimated 225 MRFs in the U.S., and the effort to eliminate the recycling escape valve had succeeded. Eureka Recycling in Saint Paul had the prescience to build their own MRF, leveraging capital from their end use markets, as Big Waste bought out local MRFs and Ramsey County closed the government-run MRF.

Mixing together all recyclables led to high levels of contamination, which was not a problem because of China’s insatiable demand for lower-cost recycled materials and their low labor costs, which allowed for labor-intensive separation at their MRFs. Moreover, empty shipping containers returning from bringing finished goods to the U.S. market allowed for low-cost deadhead shipping rates.

In 2013 this changed, as the cost of labor in China rose while contamination levels remained high. China started rejecting loads of contaminated U.S. shipments. In 2018, imports were totally shut down. It is noteworthy that China is not rejecting recyclable materials from the U.S., nor is it waiting for the U.S. to clean up its recycling. It has started sourcing materials from the U.S. directly for domestic manufacturing by investing in American paper and corrugated packaging mills and plastic and electronic scrap processing plants, thus assuring that clean recyclables or finished products are sent to Chinese industry. Chinese continued interest in the wealth within the U.S. waste stream could stimulate a new recycling wave of “clean stream” recycling that would benefit domestic markets in the U.S.

Since 2013 Coca Cola, PepsiCo, and Nestlé have been promoting statewide waste authorities under the control of a non-profit “stewardship” organization to take over recycling from local government. These plans for Extended Producer Responsibility for Paper, Packaging, and Products (EPR-PPP) fell short in California, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Minnesota. Big Soda did succeed in restricting local authority in California. The Legislature passed and the Governor signed Assembly Bill 1838, preempting rule-making responsibility at the local level in favor of the beverage industry. The legislation restricts local government from passing new fees on regulations on soda drinks and on packaging sold in supermarkets. As has been widely reported, Coke, Pepsi, and other members of the American Beverage Association signed this backroom deal with in exchange for withdrawing a ballot measure that would make all local taxes require a ⅔ vote. In other words – political blackmail.

What To Do Now

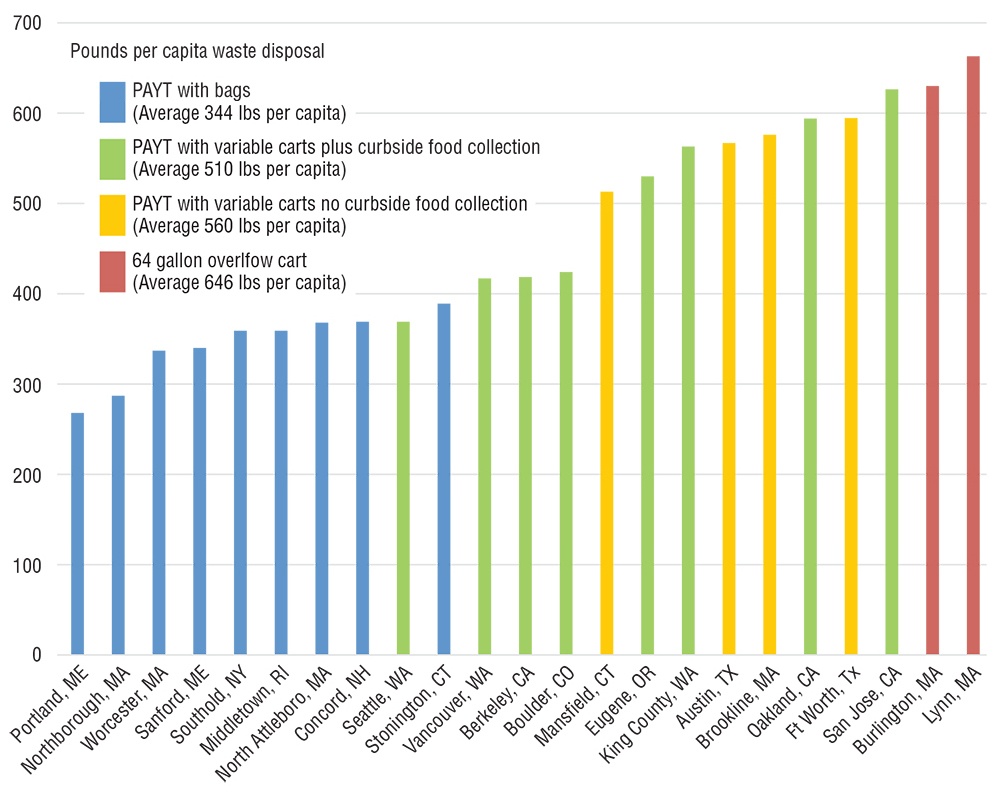

Cities and counties have to decouple recycling from the waste industry. Big Waste is the biggest recycler in the country by default. When citizens passed new rules that required recycling — such as mandatory household and business recycling/composting, and unit pricing — Big Waste complied in order to keep its contracts and market share of the industry. A smaller competing company estimates that monopoly control of the industry costs the country one-third more for solid waste and recycling services than would a truly competitive system.

Here how local governments and businesses can address the Waste Knot:

Bring dual-stream or single-stream back into the city to reduce transportation, create jobs, and implement quality control over crews or contractors. By developing marketing programs directly with end users, cities can assure that their materials meet industry specifications. Several cities have already reverted back to dual-stream programs so that their clean materials will always find markets.

Focus on composting to reduce the single largest component of the waste stream. Food waste and yard debris accounts for 35% of the waste stream in most cities, more in cities with year-round growth. Composting leads to creation of good jobs and small businesses, healthier soils, and local food production. Composting has year-round and local markets. It also conserves water and reduces greenhouse gasses by sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Implement unit pricing, or Pay As You Throw (PAYT), which can lead to a rapid doubling of the recycling rate and reduce overall waste by up to 40%. Worcester, Mass. used unit pricing to save $10 million since 1993 in avoided incinerator fees. Unit pricing has allowed cities to reduce their per capita waste generation to 1.5 lbs. per capita, down from the national average of 4.5 lbs. per capita.

Reductions in Waste Disposal in PAYT Programs

Create industrial parks reserved for recycling, composting, and reuse companies and pass waste surcharges to generate investment capital for this sector of the local and regional economy.

Small businesses can protect themselves from Big Waste pricing structures by following the model of companies like Road Runner (based in the Mid-Atlantic region). The company requires extensive source separation, provides equipment and training for staff, uses deadhead loads from traditional local fleets instead of hydraulic equipped garbage trucks to deliver materials to end users and share revenue. This allows small businesses to actually benefit from reducing their waste streams.

Larger manufacturing companies can avoid overpricing by working with specialty companies like DoxieCom International operating in the Southeast. The company claims its Sherlock Holmes reputation because it finds markets for atypical industrial by-products.

Recycling in the US need not stagnate. But our cities are stagnating under the weight of waste and beverage monopolies. Local decision-making can solve this Waste Knot by decoupling recycling from wasting.